Final installment: How to make high-speed rail a reality in the US 🔮

And Happy Halloween! 🕸️🕯️

Climate Solutions // ISSUE #89 // HOTHOUSE 2.0

See the complete high-speed rail series here: Part One, Part Two, Part Three, and Final Installment.

Last month, I backpacked Isle Royale, a remote wilderness island in Lake Superior, with my 68-year-old mom. Each night after cooking dehydrated dinners over tiny butane camping stoves, she and I curled up in our sleeping bags and, in the gathering twilight, listened to the audiobook version of David Graeber’s The Utopia of Rules.

After the sound of the late anthropologist’s audiobook faded, I found myself drawing parallels in the dark between some of Graeber’s arguments and the high-speed rail series Sam Sklar has been so expertly penning in this newsletter over the last few months.

In a section entitled, ‘Of flying cars and the declining rate of profit,’ Graeber argued that, for many who grew up in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, there was this expectation that the near-distant future would entail flying cars and space travel, among other technological wonders.

Graeber’s assertion prompted the memory of a conversation I had with my dad when I was a teen to come rushing back to mind. We were looking at a cover of TIME magazine forecasting the Singularity—the point in time when human intelligence merges with an artificial one—would happen circa 2045. Sitting on the edge of my bed that afternoon, my dad made an off-hand remark that struck me at the time: he thought we’d be on Mars by now; that we’d have flying cars.

For me, a child of the ‘90s, those things had always seemed largely like fantasy, like nice stories—as realistic as dragons or unicorns, or, at best, like something reserved for the year 3000. So it was a surprise for me to discover that an adult had actually expected such technologies to be realized in his lifetime.

But, as Graeber argued, Baby Boomers and the following generation grew up immersed in media—from The Jetsons to Star Trek—painting exactly such a future. And, up until that moment in time of the ‘70s, technological innovations had been accelerating across the board. Indeed, with an expected continued exponential growth curve of innovation, how could we simply not have flying cars and space travel, all by the year 2000?

Graeber goes on to argue that, somewhere along the way, though, antagonistic administrative and bureaucratic practices took hold, dragging humanity’s aspirations back to the ground and downshifting the trajectory of technological advancement.

The cause was twofold, according to Graeber: for one, capitalists began to realize it was advantageous to continue exploiting profit from human labor, rather than allowing technological innovation to continue at its current pace unhindered, which might eat at profits. So, instead of flying cars and robots, globalization as we know it took deeper roots.

Meanwhile, changes in the U.S. tax code in the 1970s and ‘80s incentivized a divestment from corporate research:

“Corporate taxes were slashed,” wrote Graeber. “Executives, whose compensation now increasingly took the form of stock options, began not just paying the profits to investors in dividends, but using money that would otherwise be directed toward raises, hiring, or research budgets, on stock buybacks—raising the value of the executive's portfolios, but doing nothing to further productivity.”

Between these two administrative developments, according to Graeber, technological advancement began to stall.

At its essence, The Utopia of Rules is a book about bureaucracy, administrative processes, and accounting. Which sounds boring. But part of Graeber’s theory is that the boring is precisely what we should be paying attention to because; we tend to overlook the leverage and amount of power the boring can have to shape our lives and the fate of our world.

As Graeber wrote, “Political problems are always addressed solely through administrative means.”

Of course, these often invisible elements of bureaucracy and accounting are also precisely the stuff that aspirational infrastructure projects like high-speed rail are made of. The details and processes that make possible the mundane task of our commute from Point A to Point B are oftentimes inane, but they also make or break a project’s ultimate success or failure, as Sklar shows below.

Flying cars and life on Mars are just a couple of examples of the kinds of dreams that have been dashed because only a select few individuals were paying attention to the invisible administrative priorities setting the course of our collective destiny.

What kind of world would we have if the aforementioned bureaucratic and accounting decisions hadn’t dictated so many outcomes up until this point? If we, the people, were empowered to leverage bureaucracy for lofty goals, and not just for “efficiency” or maximum capital extraction?

Would we have high-speed in the U.S. by now? What about flying cars or life on Mars?

Like many things related to mitigating climate change, a future of HSR in the U.S. necessitates that we refuse to leave our fate up to the deities of accounting and profit as we know them.

Details matter. The mundane, the nitty-gritty processes that shape our lives—they matter. And just what world might we create if we gave them our due attention?

Better yet, let’s make the tiny, invisible, and administrative not only visible, but big, conspicuous, and fascinating, as Sklar has done so well with this series.

This is to say, thank you all for sticking with this series, which often dwelled on the nitty gritty or wonkier aspects of HSR.

With that, today’s final installment of this series covers one final nitty-gritty detail to complement the seven ographies+, as well as touches on what’s next for HSR in the U.S. and (finally!) what you or your organization can do to get more rail in the ground.

🎃🔮🪄🕸️🕯️☠️

And a Happy Halloween!

Editor-in-Chief

P.s. Enjoy what you’re reading? Click here and subscribe to support this work for the long haul!

Process, what’s next, and you

Dogged, messy, essential process

By Sam Sklar

For those who wish to build, there’s one more complication to the seven ographies that I’ve left out until now.

Even projects whose outcomes feel relatively assured can still fail at any point, and it’s oftentimes because of one oh-so-necessary alchemical piece: process. It’s messy and imprecise and hard to fit into its own frame. And, it’s essential. A well-thought-out process can first dictate and then punctuate a project’s bona fides. In my professional practice as a transportation planner, and in my day-to-day exasperations (a.k.a. my infrastructure newsletter), I’m dogged about establishing a comprehensive process to ensure that results are traceable and repeatable. When all is planned and built, a finished project may not have gone swimmingly well, but at least there should be a way to track what went right or wrong, to learn what from the past to improve on for the future. This is the capacity-building I’ve been talking about.

On that note, here are a few thoughts on how planners, builders, politicians, and policy leaders can think about process when it comes to high-speed rail:

1. Communication is key or a project is doomed.

Right now there’s a disjointed, public perception of HSR, which can trickle down into individual project plans. The many stakeholders involved in a project will have differing, conflicting needs. Without a process in place to facilitate consent among stakeholders to proceed, a project—like California High-Speed Rail Authority or Texas Central—might languish in development hell indefinitely. Neither can organizations that want to build high-speed rail cannot—I repeat, cannot—assume that the value proposition, whether that’s ease of use, cost, connectivity, or climate change mitigation, is obvious to the public at any point during the development process. They need to make it so via clear communication and effective persuasion.

This is what Brightline did so well and continues to do well in Florida. The entire front page of its website clearly and precisely answers the questions: “What do I get?” and “For how much?”.

2. Acknowledge where gaps in workforce ability or capacity are and maintain a running, prioritized list of how to fill in said gaps.

Because we’re dozens of years behind our international counterparts and nearly a century separated from the original transcontinental railroad building bonanza, there just isn’t the (American) workforce capable of building complicated projects requiring expertise across all seven ographies+. Meaning we don’t have the necessary internal expertise to either run projects on our own AND/OR manage a consulting team to run them. Don’t believe me? This is a key assertion from the NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management team behind the “Transit Costs Project.” According to the Institute, we need to beef up this labor and knowledge pipeline as soon as possible by:

Incentivizing young people to enter public service, supported by higher wages and a pathway to valuable knowledge development.

Partnering with our counterparts across the globe to ensure a steady baseline of know-how continues to grow.

3. Make the permitting process easier to navigate.

Permitting and environmental review is a colossal web of procedures and often litigation. Perhaps the most well-intentioned of the environmental protections involved in the process of building infrastructure in the U.S. is a hurdle you might hear called a “NEPA” review. That stands for the “National Environmental Policy Act”, and is the guiding rule for how project developers are intended to study and mitigate potential environmental impact, including compliance with the Clean Water and Clean Air Acts. On its face, it’s a good idea. In reality, it’s often levered by bad actors to slow a project to a halt through litigation. Inertia wins, indeed.

The solution(s)? Project leaders and government agencies need to agree to clarify what factors trigger a years-long review. Second, they can telegraph and facilitate preference for remedy outside of litigation through stricter adherence to new, clearer rules. Lastly, they can allow and expect project information to be shared across departments—from the Federal Transit Administration to the Federal Railroad Administration to the Federal Highway Administration—so that each is empowered to capitalize on one another’s work.

What’s next for HSR in the US?

So what’s on the immediate horizon for HSR in the U.S.?

In truth, it’s hard to say. We’ll likely get Brightline West within five years, Texas Central within 15, and California High-Speed Rail in…the extremely distant future. With this in mind, I’d like to consider an additional headache that will, of course, throw perfectly good projects into chaos: cash infusions.

Cash is king and it’s always just out of reach.

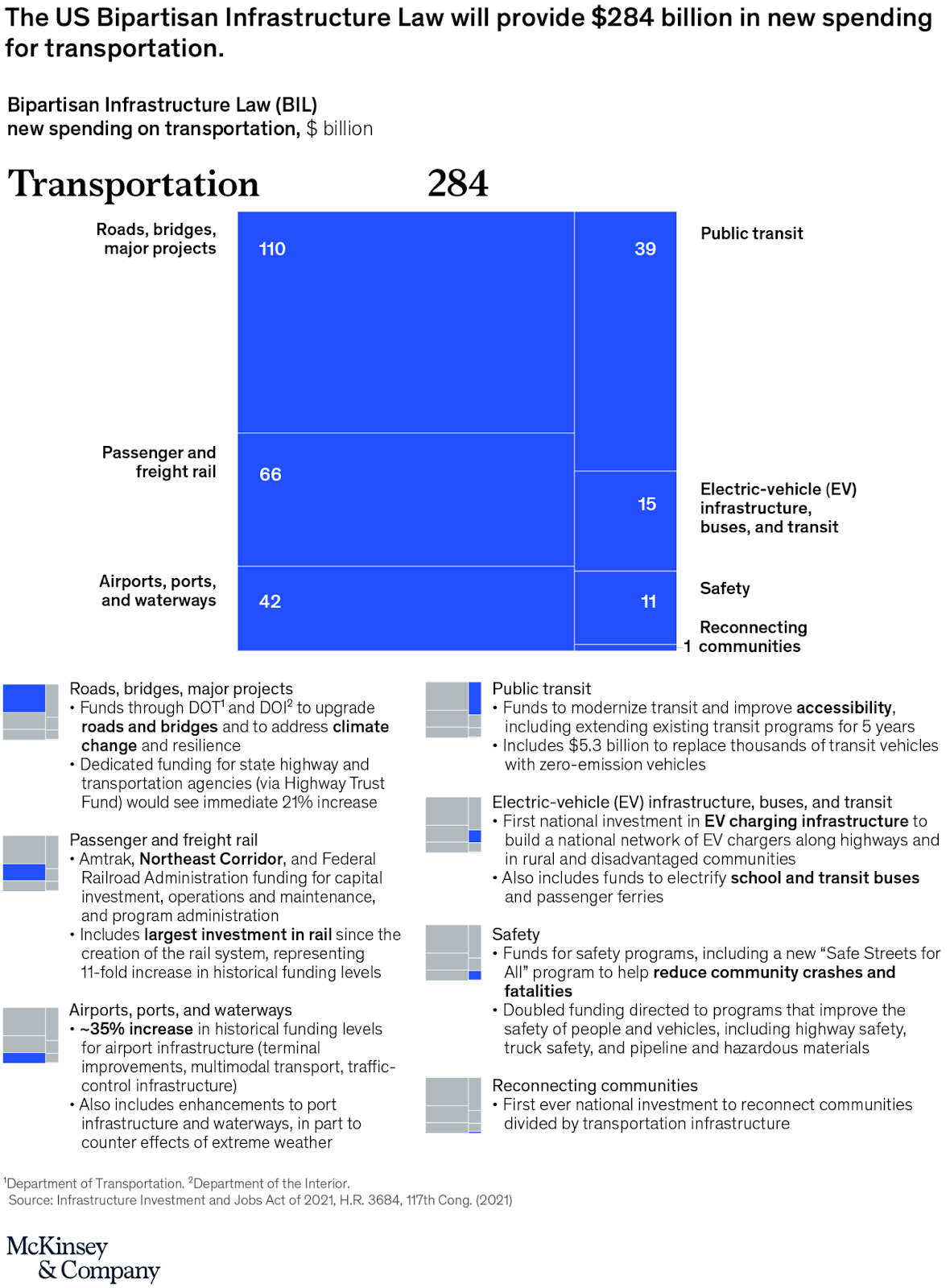

The Donkey/Elephant in the Congressional room is the current action on new Federal spending. New infrastructure cash is already approved and begging to be spent. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) of 2021 authorized over $550 billion over five years for new infrastructure, over half of which will be for transportation. A quarter of that will go to new rail investment; lots will go to upkeep and upgrades to existing rail. All-in-all, there’s is a lot of money by any measure. Surely some of that can be used to fill in California’s HSR gap. But no.

Why not? The short of it is this: rail is not a priority, and it hasn’t been a priority. Not in recent memory. If we want to see what we’re prioritizing as a nation, and how we’re valuing high-speed rail, just look at how and where we’re spending our money: almost 40% of the BIL—$110 billion—will go to highways. Plus there’s still no specific call out to build HSR.

As The Washington Post’s Steven Zeitchik wrote in late 2021, “[The BIL] contains no earmark for high-speed rail projects, the globally popular … public-transit advancement that unites cities hundreds of miles apart without an airport hassle or carbon-spewing plane in sight.”

The total investment looks like this, thanks to our friends at McKinsey & Co.

What sticks out? That’s right—no guaranteed cash for HSR. Without even the mirage of cash, there’s very little incentive for entrepreneurial planners or private companies to spend time and resources planning for any HSR alignment.

So what can you do about it?

A) If you’re an individual…

…of course, there’s very little you can do to literally build the rail, but that doesn’t mean you can’t try to influence the decision-makers who can.

Ride the train as often as possible.

This includes high-speed rail in other countries, local rail, transit, and Brightline. Choose a longer Amtrak trip over flying across the country if you can. Advocate to your friends how convenient and pleasant a trip is! Grassroots power is how political power takes root.

Contact your local politician or decision-maker.

Let them know how much you care about rail, or high-speed rail, where it makes sense. Yes, there are a ton of competing interests vying for a politician’s attention, but one that can capture it is the impending vote from a constituent. If you can, attend a town hall or other public meeting, either online or in person. Make your voice heard; join in with other voices.

Resist car culture.

Share memes and articles that denigrate and make fun of car culture and all of the resultant space wasted on parking. Buy your nephew that toy train instead of the toy car. If you can, dump your car—even if it feels like you’re cutting off a fifth limb. That’s true freedom: the freedom to resist the culture foisted upon you and the freedom to travel by any means necessary. Literally.

B) If you work at a rail operator, non-profit advocacy organization, or philanthropic/research entity…

…there’s much more you can do with your access to money and influence.

Build information campaigns around HSR that are geared toward specific audiences.

These can and should be aimed at education or action. They can be sustained or one-off. What each campaign should look like depends on the context of the rail. It should look different in Florida and in Texas, and different again in California, Chicago, and New York City. Universal threads, though, should include language that supports the development of dense housing/land use around HSR stations or messaging that dispels the notion that private companies have no role in HSR’s future. HSR is a high-profile commons problem. We so desperately need leadership to demonstrate that it’s everyone’s issue and that everyone should care, even the lil ‘ol corporation. Even if the connection is tenuous; a little bit of telegraphing a good future might help to manifest it.

Hire experts to engage internal staff at agencies.

There is a way to beef up local expertise through coordinated technical assistance. Let me rephrase what I said earlier. It’s not that no one has expertise, it’s that there isn’t yet a critical mass of expertise in the U.S. So host a series of skillshares—including tapping expertise from our friends in Europe and East Asia—to teach and solidify processes.

Fund research into the benefits of HSR.

They could pertain to environmental, social, economic, or equity impacts—ideally all of the above. We’ve got to combat bad information—or worse, no information—with well-funded, honest insights into the benefits of outfitting the U.S. with regional HSR. It’s even better if the research comes from non-partisan or bipartisan-funded sources. The last thing we need is fueling the baseless conspiracy that rail is a “liberal” agenda because we can’t be bothered to diversify our sources.

C) If you have decision-making power at any organization or company…

…think about high-speed rail as an investment in your business. There needs to be a future planet for your business to continue to exist.

Bake supporting HSR into corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) goals.

Many publicly traded organizations report on how they’re investing in the planet, in their people, and in their workday. If you’ve got influence over how to frame these efforts, include “supporting rail development to and from our worksites, etc.” as a major part of each goal area, even if it’s literally tangential. The power is in the many here. The more companies that start to think about rail as a good future business decision, the louder the movement will be.

Cover the mass transit cards of your employees.

Many organizations cover or subsidize driving to and from, as well as parking, at work. Instead, why not invest in transit vis-a-vis rail—pay for your employees to commute by any method other than car. More and more places are offering these types of benefits paired with scaled-back parking benefits that could lead to a future of an insatiable demand for transit—and connectivity to regional HSR. What a problem to have.

D) If you’re a lawmaker or staffer in a political office…

…please, for the love of God and the planet, pay attention to this issue and authorize the ability to build this important tool for access, mobility, commerce, and pleasure.

Vote on bills that provide new resources to fund rail and HSR in the U.S.

Better yet, write and sponsor or co-sponsor a bill.

Take a stand on this issue.

It’s a great way to differentiate yourself from an opponent, or even a colleague in your own house. Fight for not the mode, but the meaning behind the mode. If HSR doesn’t make sense for your constituents, then say that. But we cannot just continue to build billions in new roads.

Call hearings, bring in experts, hold town halls. Hold your state DOT and USDOT accountable.

We’re serious about climate change? We care about equity? We want to see more dollars and time in the pockets of Americans? You have the power to hold a hearing on specific issues. The reason transportation is at the bottom of the list of “issues voters care about” is because that’s where it’s always been. Good transportation is effortless and silent; transportation should never be the focus of one’s day (unless it is). Bring local and national storytellers together to share how better rail access could change the lives of your constituents and communities.

This one’s for staffers: talk to your member.

Relay your concerns and help your policymaker shape their message and their image.

Here I’d like to extend an invitation to you, dear readers, to share your thoughts below. Do you have other ideas on how to advance HSR here in the U.S.? What did you think of this series overall? Was anything major missing?

Cheers,

Cadence Bambenek

Hothouse is a climate action newsletter edited by Cadence Bambenek, with supplemental editing by Peter Guy Witzig on this issue. We rely on readers to support us, and everything we publish is free to read. Follow us on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Thank you to the readers, paying subscribers, and partners who believe in our mission. We couldn’t do this work without you.