Adam Paul Susaneck on the Past, Present, and Future of Transportation

The architect and urbanist behind "Segregation by Design" dishes on reconnecting Rochester, the graphic approach to questioning everything, and transportation as identity politics.

I’m fortunate to meet the people behind the decisions, good and bad, that help to define the dysfunction and dedication inside the transportation world. We don’t spend money right; we don’t communicate effectively; we don’t take credit for the wins and own up to the Ls. The ship, steered by great leadership, will need to turn toward a just and equitable, dignified, and safe future, screeching and creaking in all. Sometimes, I’m fortunate to talk to the people behind the people behind the decisions—Adam Paul Susaneck is one such person. By trade, he’s an architect and publicly people know him by is moniker and work as “Segregation by Design.”

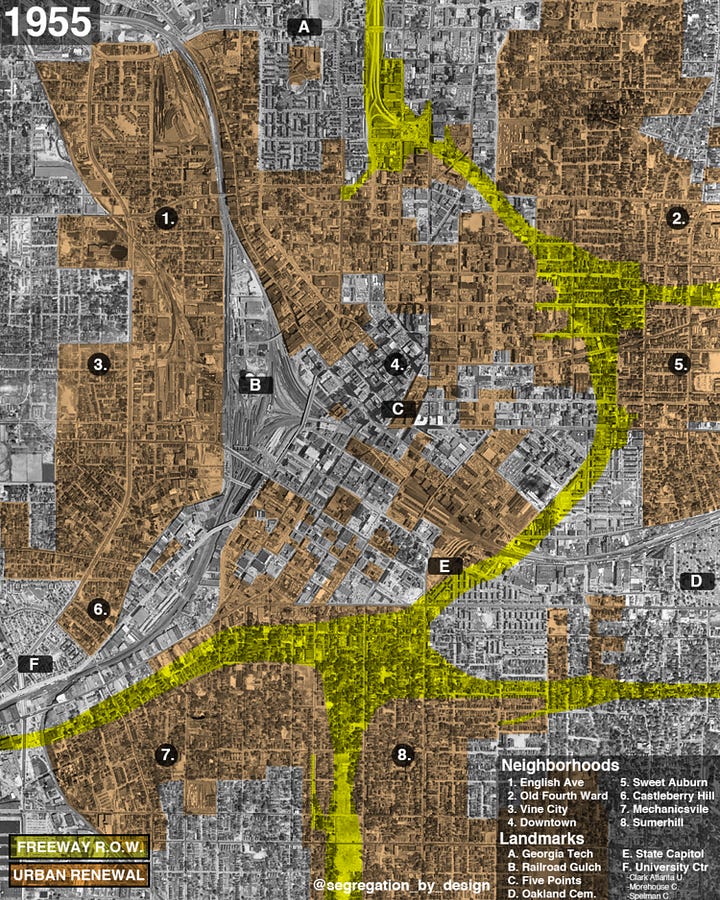

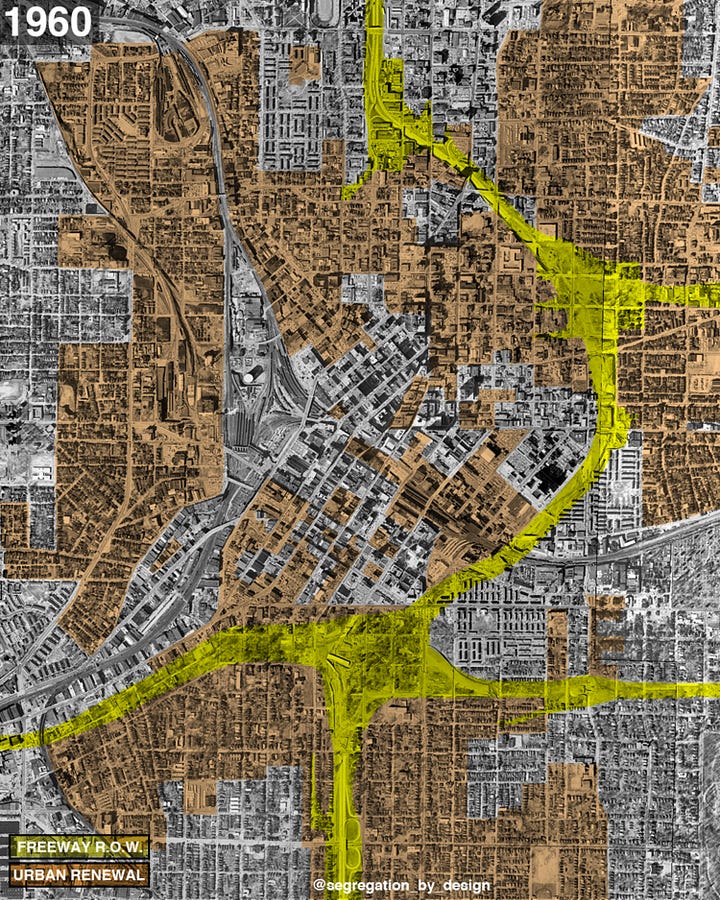

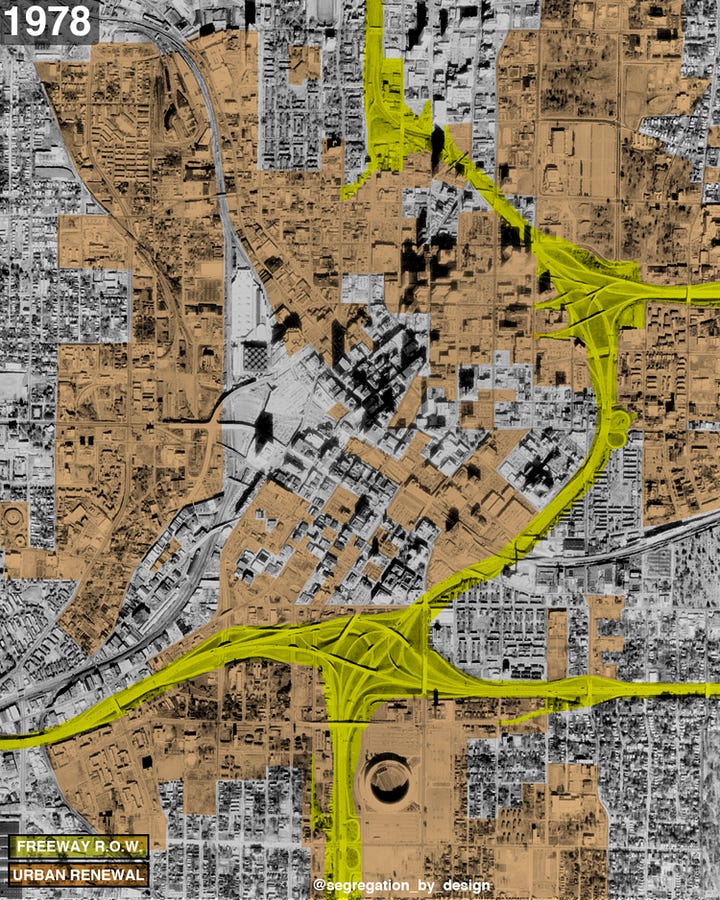

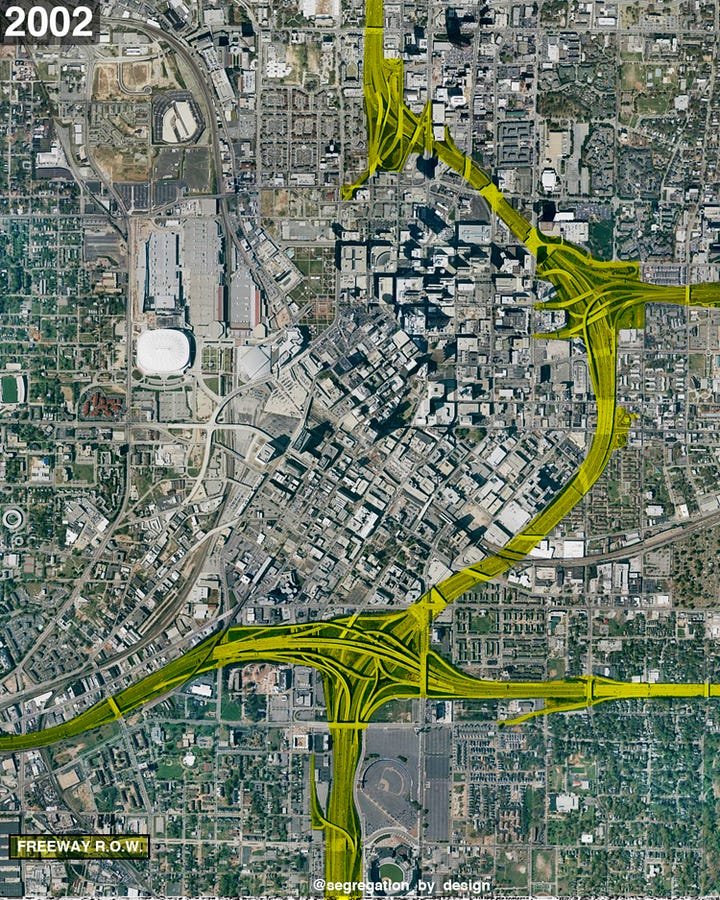

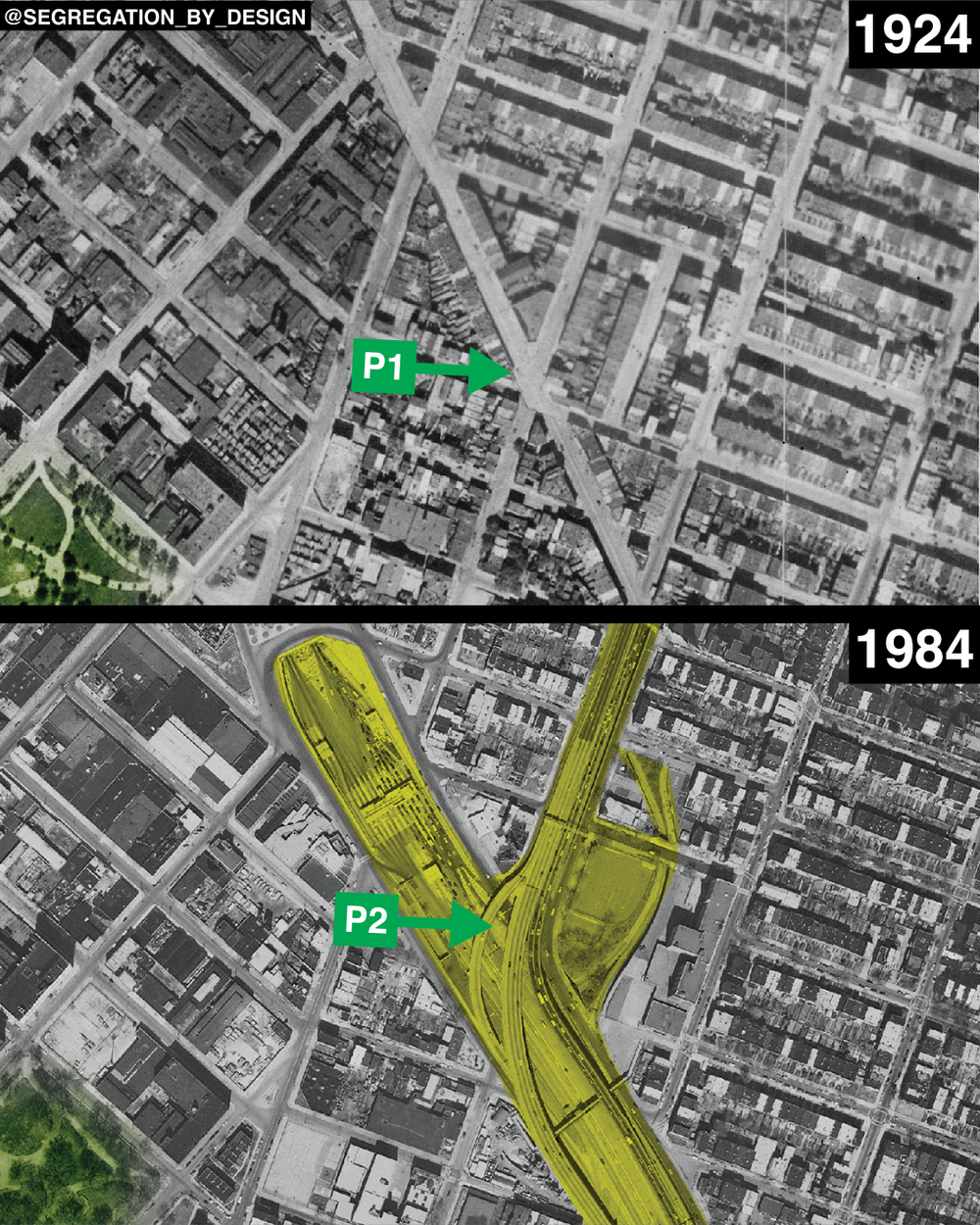

Segregation by Design is a multimedia platform that conscripts old maps and modern technology to show and tell how we, as a society actively chose to rip up community and replace it with highways and other infrastructure “meant” to connect, but instead, well, segregated. Adam’s work has been syndicated and he’s had an opportunity to write for major news outlets, including The New York Times.

Our interview is below—we talked for a long time and this interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Make sure you follow Segregation by Design on all platforms, but especially Instagram.

I'm Adam Paul Susaneck. I am an architect and I run the account “Segregation By Design.”

Why did you start this project?

There are a couple of different answers to that.

The joke answer is that I wanted to figure out where the streetcars went and I fell down a rabbit hole that led me to realize that we basically dismantled our cities in the name of racial suburbanization and segregation. It’s a monumental injustice that this story has been told in such a way that people like me are primarily the ones with access to it.

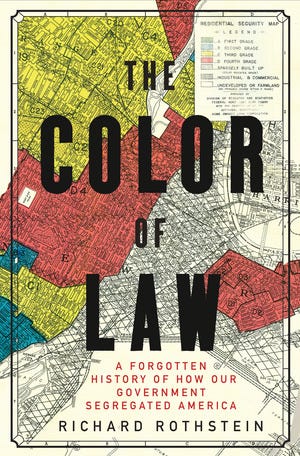

A few years ago, I read Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law. It’s a succinct book, but as a visual person, I was frustrated because it didn't have more visual examples of what the built environment is really like. Rothstein talked about desolation and destruction, and we didn't see the images of desolation and destruction. I’m a cis, hetero, white dude. I’m about as far removed from the reality of the situation, but I’m trained as an architect and felt I had the tools to show what happened. I use the before and after pictures as primary sources and layer them on top of the aerial photographs. That's why I love aerial photographs because, to some extent, they speak for themselves.

More cities should follow Rochester’s lead.

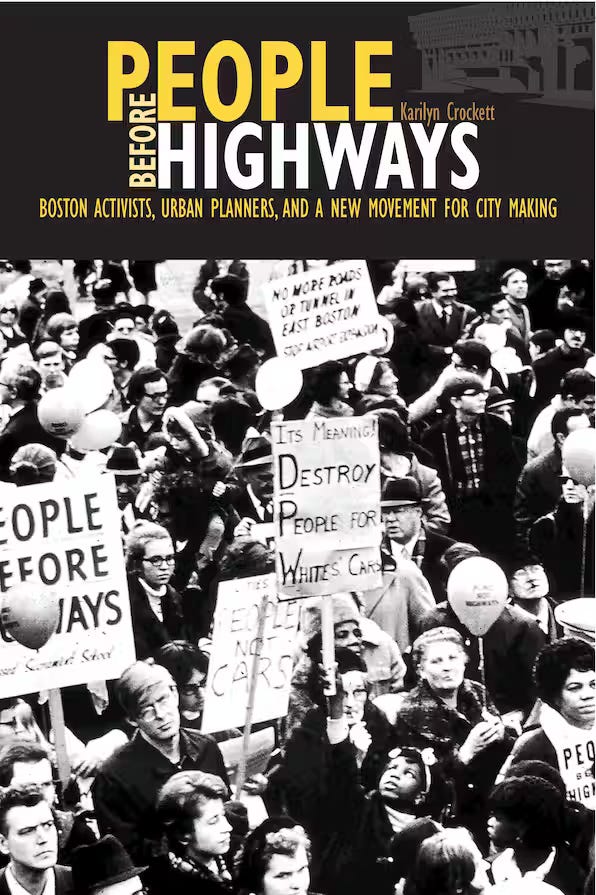

I intend the project as a sort of visual companion to a book like The Color of Law and at the city level, there’s The Power Broker for the Bronx; Boston, there's People Before Highways; for Oakland, Hella Town. Because it is it's how we communicate these days. The output of the project, so far, is powerful to show in mages because what we did was so stark.

We're trying to fix these big problems that ripped apart our cities. It’s been precipitated by the failure of the infrastructure itself—the roads are old and crumbling—but then the social justice movement around just highlighting these systemic injustices, like the fact that if you live near one of these big projects, which the builders forced you to do, you're going to get asthma.

If we're going to fix these problems, we have to center this whole question of social justice. We have to pay attention—we can't pretend to be colorblind, and we have to look at outcomes and what caused these outcomes. And we must be clear-eyed about the fact that a lot of the building and desolation and destruction was intentional. And we're going to have to be just as intentional to undo it.

Sounds like it was…segregation by design.

The name “Segregation by Design” refers specifically to the practice of redlining as the policy genesis of intentional segregation at a federal level. When I show a picture of Haymarket Square in Boston being torn down for building Boston’s old City Hall—it’s not a Black neighborhood and not even a residential neighborhood.

Pulling capital from the city center to the suburbs cemented this evolving idea of what a city is, that it should be accessible by white suburbanites by car. Simultaneously, density was racialized. The architect wasn't a racist, but he was taking part in a movement that ingrained segregation into our built environment by remaking downtown, in the middle of Boston, parking lots for suburban commuters. The builders bulldozed density to place the central artery right through Boston.

With a lot of recent focus on social justice, incentives have been in the process of updating. Change is not going to happen all at once or immediately, which is unfortunate, because there are immediate problems that we must address.

There may be a margin of incentives that's shrinking between the social incentives and the fiscal incentives. Hopefully, they'll continue to converge.

I’d say that most architects are not necessarily urbanists, which I was very surprised by. For many architects, building is about crafting a beautiful object and the city is …an annoyance.

From my understanding, certain schools teach that the big picture is you're the spatial artist and you author the space and totally treat context as secondary. This isn’t every architect or every school or every idea. But the underlying disconnect exists and that's where the tension between architects and planners comes into play. Planners supposedly look at the bigger picture and architects…stay very confined. We’re all talking past each other because there's very little social curriculum involved in architecture, because it's a two- or three-year program, and you’ve got to learn BIM modeling and materials. science, and…

Architecture was a career shift. I was at Google before doing event planning because I did PoliSci undergrad at Berkeley. I wanted to go into government, but then the government became…what it was.

I did a post-bac program and learned how to draft and became an architectural designer. At this point, I’m working at a more urban scale. Architecture curriculum doesn't teach you to care and I'm very surprised at how few architects are also urbanists. I thought it went hand in hand, but, no, people don't have any idea.

[Ed. Adam’s since taken on a role as a Project Manager of Trasformative Infrastructure at AECOM and is pursuing a Ph.D. in Urban Planning at TU Delft in the Netherlands.]

Some architects call themselves urbanists. Historically, Frank Lloyd Wright thought the greatest opportunity was to build every person an acre that would then connect to each other through the freedom of the car. It’s a complete and fundamental misunderstanding of human behavior.

I also don't speak for individual architects, but you could always tell which architects had a sense of human behavior by how many people were in their renderings. And how the people were behaving in the space. They would create a veranda or a public porch that was not just for show and was programmed and accessible for people. I always appreciated these small details, except just because they’re small doesn’t mean they’re last.

The last step is adding people, which is funny [Ed. Funny…how?] now that I think about it. Whenever we make renderings, the last step is throwing in people and trees. And you always do it the morning of the crit because you stayed up all night.

Back to the project…I got to thinking about how an ideology can become a pathology, like this idea of modernism can metastasize into tearing down the whole middle of the city, blithely, because it looks cool on paper. It gave me an insight into how insular architecture really is: the architecture school doesn't talk to the engineering school; architects don't talk to the urban planning students right next door. We don't speak to the preservationists even though we're in New York—New York!

There was that great piece in Politico a couple of years ago that really focuses on the “vetocracy” around Penn Station. Francis Fukuyama coined. He did coin this idea of vetocracy, which then Ezra Klein picked up a couple of years ago and I think they’re both right that there's so much opportunity to say “no” in decision-making now. It’s either so litigious that a project never gets out of the idea stage or if it does make it into the churn of project development everyone's afraid of being left holding the hot potato when everything falls down. So instead of fighting the problem, they fight each other to decide who is the least liable for the eventual massive cost overrun or broken project stream. It’s always been helpful to think through this lens, this lens of …we don't have a democratic style. We have a vetocratic system of government where everything is “no’d” and hacked apart until the shell of a project is all that’s left.

I think it's an interesting way to frame how we're approaching problem-solving. It's Alan Altshuler, at some point, wrote this idea that overlong megaproject development is built into the political structure of capitalism and how we build things because there’s no incentive to fight a problem together anymore (if there ever was) because there's no ego in winning against an abstract ether of an issue.

If you can defeat a real opponent in real life, then you've demonstrated your ability to get reelected or your ability to earn more money.

There’s a serious and deep-seated problem of misaligned incentives and organizing and building minority power until it becomes majority power might work to offset the rumble and tumble of late-stage capitalism. Shame works, too, but shame works differently and there’s more nuance to it—which is not a friend of social media and the other tools we have. We do have the tools and we're still not doing either. We're still not communicating correctly.

I don't know if we're not communicating correctly, but that’s potentially a part of it…I don't know if I agree with the idea of “vetocracy…” Did you read the book The Sum of Us by Heather McGhee?

During the New Deal, one of the things they built a ton of was public pools and a lot of public spaces, Beaux Arts and Neoclassical public spaces, and a lot of them still exist... We've got a lot of beautiful libraries. They also built a lot of these public pools. And they were segregated. They were whites only, legally. In the ‘50s and ‘60s, the laws changed. But rather than integrate the pools…what they did was demolish them.

And after that happens, that's when you see the rise of, especially in the North, private pools in people’s backyards. The effects of this policy meant that poor people no longer had a programmed place to be in public. We privatized the public good to avoid racial integration.

So when I hear vetocracy and “no one wants to be holding the hot potato” it's also no one wants to expend any energy to do anything for anybody but themselves. It's not just saying no because they don't want to be holding the hot potato, they’re saying no, because “I got mine, f**k you.”

That's San Francisco. That's what the entire city of San Francisco’s housing policy is: “I got mine, f**k you, move to Antioch.” I don't know if I would call what’s happening vetocracy because that implies that they're intentionally saying no, because they have some idea of “This is for the good.” They don't want to do anything because they don't want to do anything. Because we've set it up as any game for one is at the expense of another,

Integration? No, we tear down the pool, we move to the suburbs. We don't share. We don't build; you don't get to move around. We don't build trains; you buy a car.

There are NIMBYs in other countries, but it's a different type of NIMBY. They're not opposed to the very idea of transit, Here: “Oh, it's a Democrat boondoggle.” Transportation is an identity politics issue.

What it means is if there's going to be a project, right? “We're going to rebuild Penn Station!” or “We're going to build some sort of station where people can go get a train because New York still does run on trains, the pathology, as you called it is threefold, and it cascades. A: we can't even determine or identify that there is a problem at all; B; If, and it’s not at all guaranteed, that we determine that there's a problem, nobody can agree on what it is or how to frame it; and C, because nobody can agree on what problem we're trying to solve is the game shifts to who is going to be caught holding the potato when there's an eventual snafu.

In the United States, every single project (sometimes even routine maintenance!) in the country is like this. I don’t know if it’s obvious, but I'm also not particularly optimistic. I'm making it my life's goal to at least move this needle in a positive direction. That's where I'm at: how can I develop, define, and communicate the problem I’m trying to solve?

That is why this communication piece is so important. It's the first step and that's why I’m running “Segregation by Design,” to raise awareness.

Furthermore, we can see examples of what works, which we weren’t used to be able to do. On the internet, we can see examples of good things, and seeing them is the first step because a lot of people just haven't even thought about this stuff... The first step is seeing images of modern trains and realizing, “What the hell are we doing here?” We could also use more collaboration with international partners that have more experience building trains, like SNCF or RATP.

Josh Barro wrote a piece for the Intelligencer for the New York Magazine about how the GAO commissioned a report to figure out why building infrastructure in the US was so expensive and why we can't align ourselves to international best practices. Barro reported that the GAO report came back with empty hands because there’s always a problem and the problem is here is a classic principal-agent Catch-22: You can't get people to talk about their expertise, because they’re either bound by NDA or lack of incentive—why would professionals give away their expertise for free when others are perfectly willing to But paying by paying them, you're tainting their ability to talk about their work freely, because they’re incentivized to give answers that get them paid, correct or not.

That's graft. That’s just graft.

Of course, it is! We know the answer. It’s like Schrödinger’s transit system: once we observe it, we see that the observation itself changes.

Last question. Is there hope for the future—what does “success” look like?

What does success look like? It's easy to say Amsterdam and Delft and Rotterdam, are my favorite places in the world. And for us in North America, it's even easier to say Vancouver. But look, the fact of the matter is those cities made the right decisions at the time and didn't build highways (or at least as many). And that was the thing to have done. But that was 50 years ago.

Houston is never going to be Vancouver and it's never going to be Amsterdam. We idolize Amsterdam and Oslo, too, for good reason. It's easy to say Amsterdam; it's easy to say Oslo; it's easy to say Paris. But I think more realistically, Rochester, NY is a really great example. They’ve torn down part of their downtown highway and rebuilt housing on the former right of way.

Seoul is another really great example, because of the Cheonggyecheon restoration project. Seoul is also not too different in scale from a place like NYC (it’s actually bigger). And this is an easy answer only in theory because we tend to be reductionist about the But when they built Cheonggyecheon they didn't just tear down the highway, they built two adjacent subway lines. That’s the key.

It's not so much taking something away as it is providing overwhelming, alternative opportunities for access.

Which is absolutely the thing to do when tearing down American highways. To turn back to the US, there’s a difference between I-980 in Oakland, which is a pointless highway, and the Cross Bronx, in New York, which, unfortunately, is a critical link to jobs, warehouses—the whole Northeast Corridor.

So, the example for us would be to rebuild some freight rail or reroute some of the truck traffic away from the George Washington Bridge. And you know, we just finished the overbuilt Mario Cuomo Bridge…maybe let's divert some truck traffic up there and off the GW Bridge. We don't need to send regional truck traffic through the Bronx.

A Bronx resident had no power to stop Moses from building this road. He just did what he wanted.

People will say, “But it was mostly white at the time!”. The country is still mostly white—it's the fact that 10% was enough—that 10% was targeted. They also targeted Jews. That's what people keep saying about Roxbury in Boston. They were redlined, too.

What else?

For some reason, Rochester, NY pulled together the political will to act. Rochester used to have this highway loop that used to go all the way around downtown.

And they didn't tear it down and make it into a boulevard. They tore it down and just straight-up filled it in and then guess what they did? Affordable housing. They put back together the grid. They didn't do what Boston did: bury the highway and just cement a car-based future, Rochester demolished the highway and reconnected the grid and they built affordable housing. More cities should follow Rochester’s lead.

Anything you want to plug?

My Patreon! And follow me on all the social media accounts.

Adam Paul is right on. Readers may be interested in a study I did on Troy NY regarding its rise as a TOD and then loss of its trolleys. Critical Federal events in 1920 are traced as the when we lost the TOD form. Article may be found at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1osRRvfLGEZqRPuRk1M2b_2gFxdvoFWPt/view?usp=sharing

Welcome back!