The Best Book I Read All Year

Hold your nose and hope for thes best. It's not "Life After Cars," but something totally different.

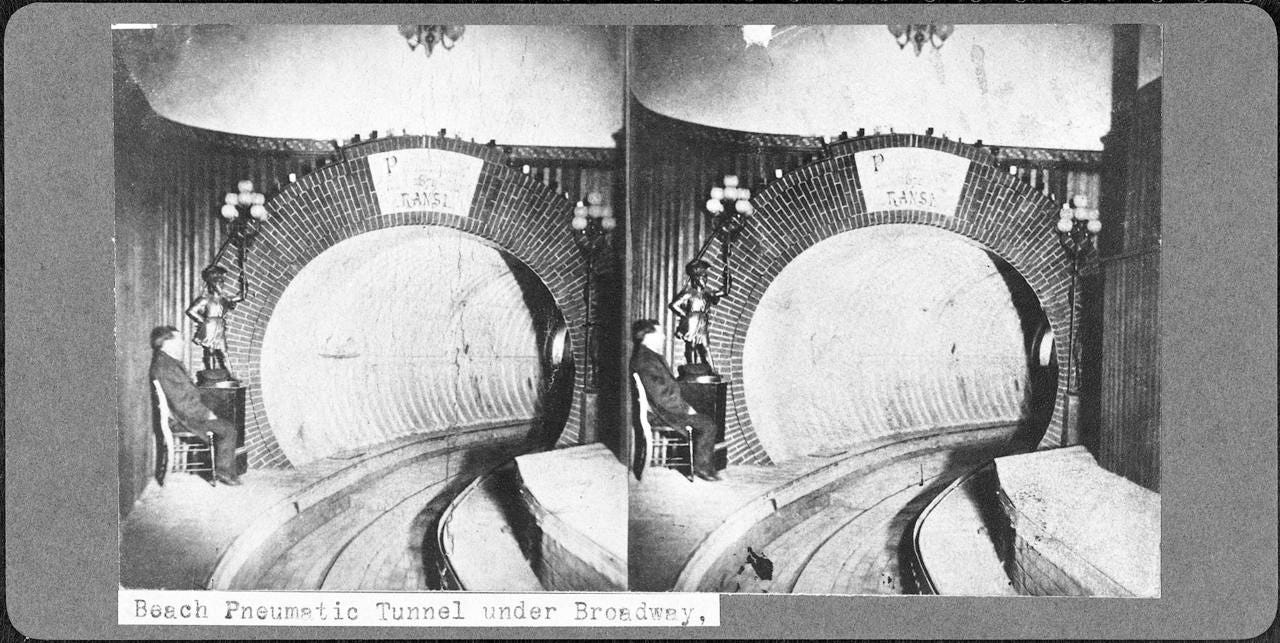

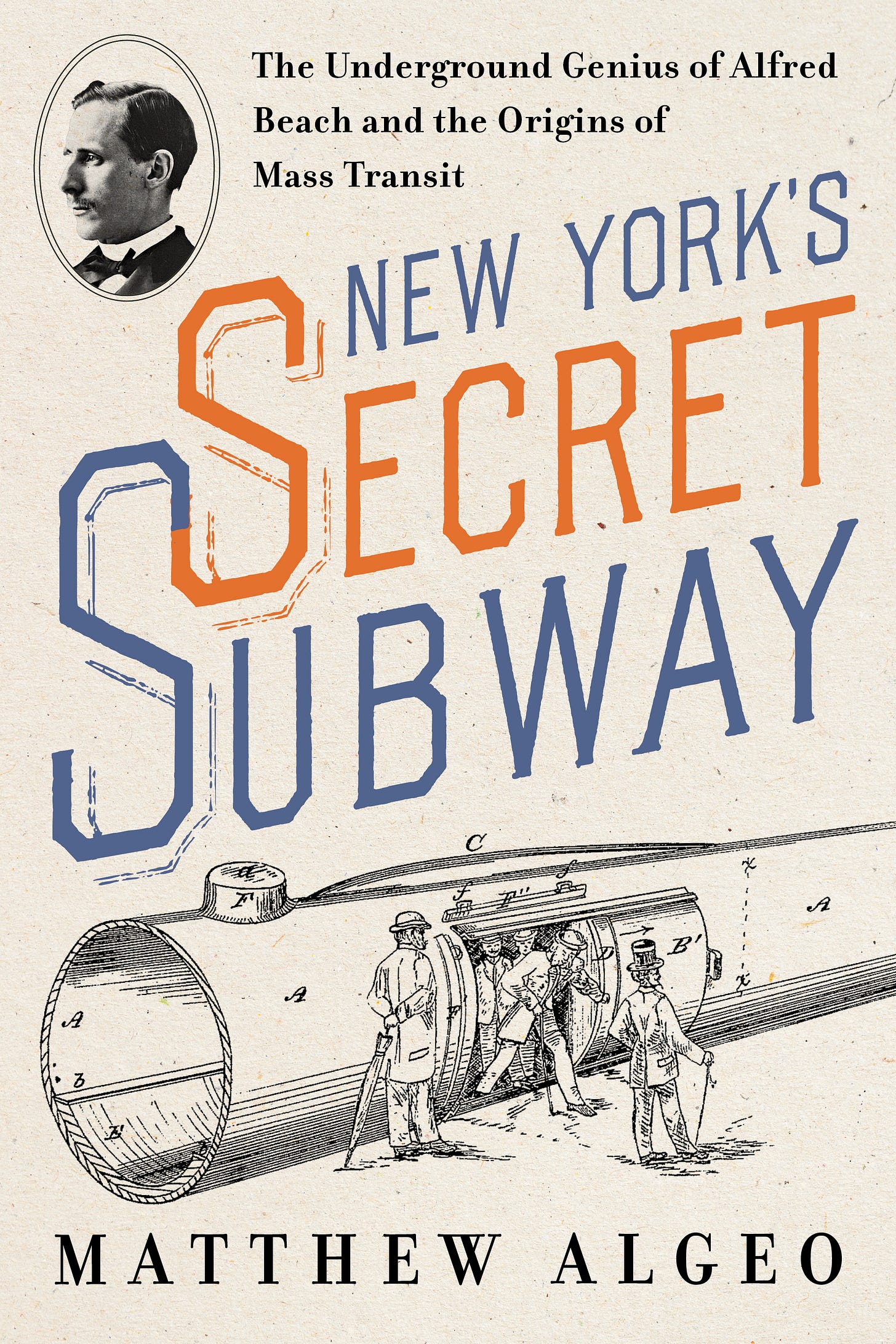

I really did like Life After Cars — Doug, Sarah, and Aaron. Bravo, and/but New York’s Secret Subway brought me on a journey detailing life before cars, and it will surely enthrall you, my exasperated friend. The plot is somewhat straightforward: Alfred Ely Beach wanted to build a pneumatic underground railway to show it could be done. His sub-way would not be steam, coal, or electric, but operated using a practical application of Bernoulli’s fluid dynamics: by fanning air through a tube large enough to push a car back and forth. He did it. Kind of. End of story.

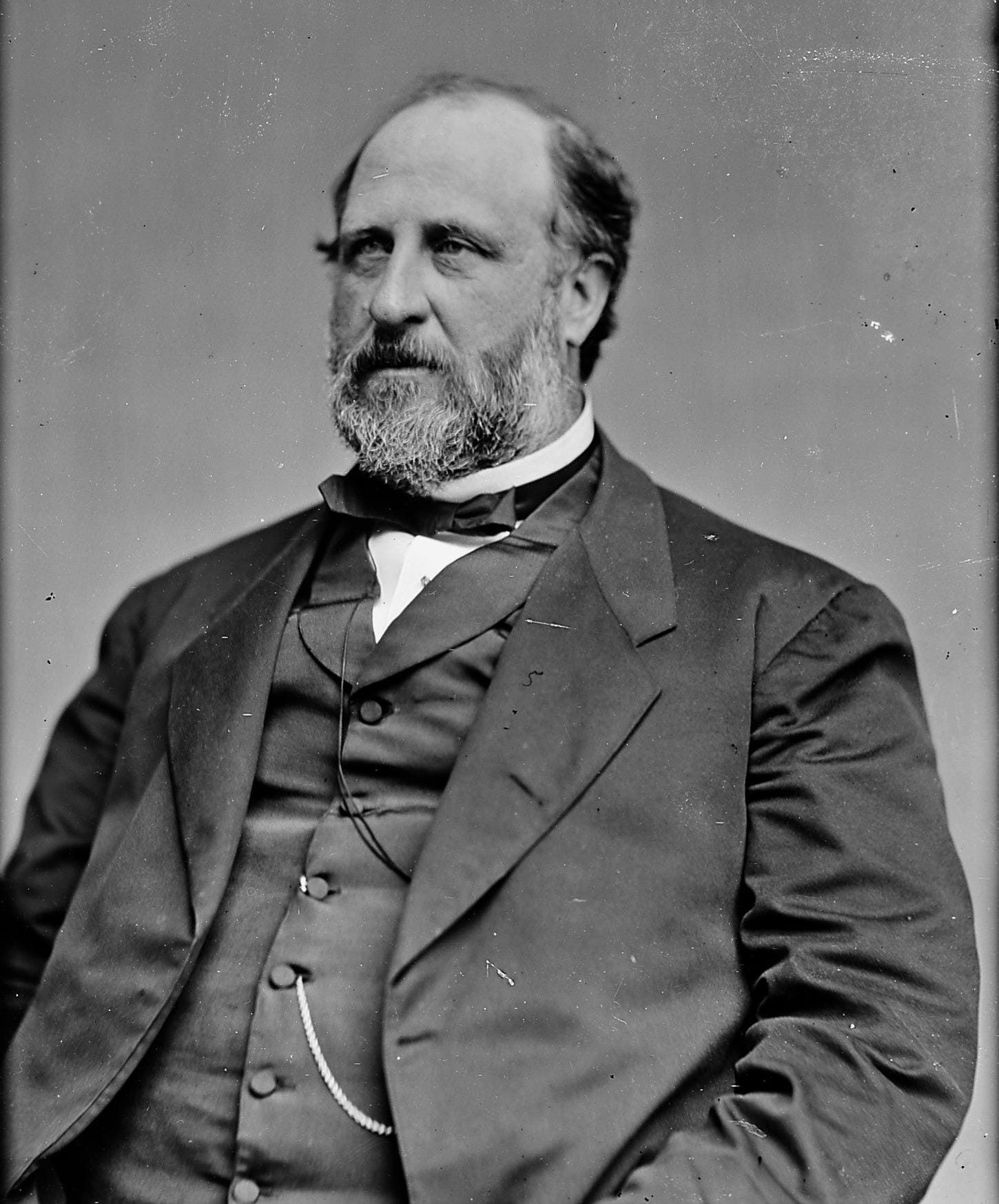

Except Matthew Algeo’s New York’s Secret Subway weaves a much larger story about New York City during the height of machine politics and Tammany Hall. Boss Tweed—the notorious Trumpian figure from the second half of the nineteenth century—plays his role as a heel to perfection in this story. But the story’s main character, Algeo argues, deserves a place in the American Inventor’s Hall of Fame beyond his contributions to public transit. Alfred Beach, forgotten to the annals of history until now, is still responsible for about two percent of all patents ever recorded since the United States began keeping such records in the mid-1800s. The pneumatic tunnel he built in secret (in plain sight) remains what he’s best known for. His legacy will continue to grow as long as books like Algeo’s continue to tell his story.

Algeo’s book is a worthy entry into the growing history of infrastructure and political history as a proxy for human ambition and the complex relationships we all share with the built environment. I spoke with him a few months ago about Beach, Tweed, Elon Musk, Robert Moses, and why holding your nose and hoping for the best is the national motto in waiting.

Tell us a little about yourself and how this book came to be.

I’m an author and journalist. I’m the host of Morning Edition on Kansas Public Radio right now. New York Secret Subway is my eighth book. I first heard the story about five years ago. A rock band called Klaatu did a song called “Sub-Rosa Subway,” which tells the story of Alfred Beach and the construction of the underground pneumatic subway in 1870…which is not typical material for a seventies prog rock band, but it really got me interested in the story. I went down the proverbial rabbit hole and here I am five years later, having written a book about it. It’s just such an interesting story, with such interesting characters in an interesting time and place. And it just, it just kept getting better and better the more I researched it. So here we are.

I wholeheartedly agree with the idea of how interesting this book is. When I first picked it up, I read the first two chapters, and I was thinking to myself, “How is this guy going to get an entire book out of this one small project underneath Broadway in the mid nineteenth century?” And as I kept reading, I realized it was less about the project itself and more about the cast of characters and the political climate and the context about which this is telling a story about New York.

No to over not to overhype it, but it was giving very Caro in terms of the approach, the reverence, and the attention you gave to your cast of characters. Can you talk a little bit about your process, about how you decided to put the edges on it?

When you begin researching it, you’re never quite sure if there’s enough there. I have authored books before—I will call them small stories—that talk about bigger themes.

I tried to make a book about life in New York in 1870, which is a period that gets overlooked in US history, that period between the Civil War and World War I. And it’s such a phenomenal period in the history of the country and the history of New York City. There’s so much is going on in this story that gets lost in the shuffle in the grand scheme of things, in the history of New York City. Alfred Beach’s pneumatic subway in and of itself isn’t exactly a huge story, but all the characters that are involved in this and all the themes that are involved in this: mass transit, political corruption, invention and innovation in mid-nineteenth century America, are. It really is one of those stories that has so many layers, so many tentacles going out into so many different subjects.

I did a book about pedestrianism, the competitive walking craze in the 1870s and 1880s, which largely took place in New York, too, and it was constructed the same way. You’re really using the small story to tell a much bigger story about America and about New York at the time. I love to be mentioned literally in the same breath as Caro—something I’m clearly not worthy of. But I love The Power Broker, and I love the LBJ books, and I love the way he is able to weave things in. And I do try to do that in my own little way.

Boss Tweed is one of those characters that is immortalized in this unfinished history of the US between reconstruction and World War I in a lot of ways. He’s not even the prototype because, for sure, before Boss Tweed, there was somebody else who was interested in corruption. His life just happened to coincide with your book; but I’m curious if you see parallels between Boss Tweed and Robert Moses? Do you think that he was Mosesian?

You’re right, Boss Tweed didn’t appear out of nowhere. I mean, he was building on a long tradition of political corruption and graft that, in fact, goes back to the founding of Tammany Hall itself in the late 1700s and early 1800s. I think what he saw himself doing was perfectly normal. He just happened to do it on a scale that had never been attempted before.

If you think of America industrializing in the period after the Civil War, with mass production becoming possible, he just saw himself as an entrepreneur on the scale of Carnegie or Vanderbilt, right? His business was political, so for him, it wasn’t as big a deal.

There are parallels with Tweed and Robert Moses to some extent. I think there are better parallels between Tweed and some contemporary politicians, and I don’t want to get too into the weeds with this comparison to President Trump. I’m not at all suggesting he’s as corrupt as Tweed.

That remains to be seen, but he and Trump both engendered a loyalty among their working-class followers that is just hard to comprehend. Remember, Tweed himself was not Irish. He was of Scottish descent. He wasn’t Catholic, yet he was beloved by the Irish Catholic immigrants who came to the US, and especially in New York, by the tens of thousands in the 1860s.

I see really striking similarities between Trump and Tweed in that respect, and in the respect that he wanted to be perceived as wealthy. Tweed had a huge mansion on Fifth Avenue. I mean, the guy was a state senator. His annual salary was…$5,000 a year. It was hard to explain how he had this tremendous wealth, but he didn’t mind at all. He had tremendous loyalty. He knew how to get out the vote. He knew how to manipulate votes as well. He knew how to manipulate elections. And so, I see a lot of parallels, not just with President Trump, but also with a lot of modern politicians.

Tweed really set the mold for the modern, power-hungry politician. And politicians learned something from him and are more careful about it now.

One of the other things that I loved about this book and I haven’t read any of your other books yet, and I’m excited to now, but I love the way that you take a very “fiction” approach to the way you tell your stories, how you build narratives that weave their way in and out of different chapters. I found this style particularly compelling. You’ll start a story in one chapter, introduce several more characters in the next chapter, and then bring it back around by adding such a rich color of the environment and the people, and some of these names that are very familiar to New Yorkers today, like Astors and the Pierreponts and the Havemeyers, all these different characters. It gives people who live in New York special appreciation and for those who don’t live in New York or who haven’t, it gives a peek under the hood of how New York City politics worked in the late nineteenth century.

I’m curious if you have any tips or tricks for aspiring writers on how to tell a story—maybe a kernel of truth, now, having written seven books besides this one.

The key is finding a story that attracts those characters. You can’t contrive ways to introduce those characters; they have to appear naturally in the course of the story. Going back to Caro, the Power Broker, Moses is the main character, but he’s also the excuse for Caro to write about all these other amazing characters in the story.

As soon as I knew that Beach and Tweed had a connection, you’re now connected to the New York City municipal government in 1869 and 1870, and Tweed gets elected to the state legislature. And now you get to talk about state politics, which was also involved in this story. Right there, you’ve got a whole stadium full of interesting characters that are going to help you write the story.

I tried to spread it out a little bit, bring characters in, and let them rest for a little bit, and then bring them back in again. It was also a way to try to give readers a break from Beach. It’s always Beach, Beach, Beach, Beach, Beach. What you want to do is give your readers a little time away from the main characters and even the main story. I go into these sidetracks about the history of mathematics and George Medhurst's experiments. I don’t know if there’s any interest to anybody, but it gives readers a little relief from the main story. New York’s Secret Subway is a very heavy political process story. So, it’s also helpful to have side characters and stories to make the read a little easier.

The story is also a history of the media in the nineteenth century, which I found fascinating as well, and which I also think is a great lesson for folks looking to read or write about the history of city building and urbanism, and science as well. There’s always commentary on what’s happening in the built environment, and planners would be good to learn about how what they say interacts with the people who are going to be commenting on their work. A lot of planners think that we exist outside of the media circus in a lot of ways.

My point here is about the history of media and the fact that Beach was one of the founders of Scientific American, which is a magazine that’s now almost two hundred years old and still has a mainstay in our collective experience of science journalism and reporting.

One of the things that I learned about how to read media in the nineteenth century is that major players and stories are all deeply, deeply connected in a lot of ways to distant or recent past. The names that we learn about in the seventeenth century come back in the nineteenth century.

Why do Orangemen march? The Twelfth of July explained

I loved your aside about the 12th of July protest. That was a great learning experience for me. I didn’t realize that it still exists in New York in some way or another, hopefully not as violently as it was back in the 1800s.

Beach was savvy. He came from a media background, as you mentioned. His father was a New York Sun reporter. His brother, Moses, was a state lawmaker. Beach was no babe in the woods when it came to media and politics. He did not live in a bubble. He knew he had a good idea, but he also knew he had to sell the idea to convince people it was a good idea.

A lot of times, architects don’t know much about the history of architecture, and sometimes they have become so convinced that their ideas are so good that there is no compromise. Beach was brilliant in this way. He invited the reporters down to the grand opening. Those were the first people he thought of—the New York Times, the New York Sun, the New York Post. Absolutely right that he was thinking about how this project would be written about, commented on.

Let’s talk about his role in the patent procedure. You colored this man as not just an advocate for trains and rail. It was one of his many ideas.

I don’t think this was the comparison that you were necessarily going for, and I don’t think there is a one-to-one comparison because there are big differences between these two men, but does the pneumatic tube idea not have this, at least a slight comparison with Elon Musk and his Hyperloop? There’s a little bit of fighting for an idea that no one believes in and thinks the technology is right. Did that enter your in in your thinking as you were as you were learning about Beach?

Yeah, it did, and it has to. The comparison is so obvious. I will say that Beach had one advantage in that the technology he was working with had been proven to be pretty successful. The Hyperloop, using magnetic propulsion, hasn’t really demonstrated that it’s feasible. Beach also started very small: let’s build three hundred feet of this thing and show it can work. I don’t know if there’s been a successful working model of the Hyperloop.

The problem was propulsion, right? This is always the problem: steam locomotives in a tunnel, there’s smoke and cinders and horses pulling streetcars and stagecoaches, there’s effluences, a lot of horse poop and pee. That was the beauty of Beach’s idea. It was so much cleaner than the alternatives at the time. It was so much more comfortable, and it was so much more efficient that it was obvious to anyone who walked down the tunnel, even just rode that three hundred feet, that this was superior to what they already have. And we have yet to get there with the Hyperloop. Someday, we will get in a tube and be able to just even go from Santa Monica to downtown LA. In Beach’s case, people were able to see that this was a superior method.

An obvious difference is we’re now one hundred and fifty years smarter, theoretically, at putting stuff in the ground. There’s very little trench-and-cover building done anymore. I mean, even tunnel boring machines (TBMs) have serious issues, including the Bertha fiasco in Seattle, which got the state DOT commissioner fired, and so modern building is steeped in navigating a different set of political realities.

It is hard to measure what Elon’s intent is here with the Hyperloop. If it’s for selling Teslas, I understand that, but if it’s just he doesn’t like buses, that’s a very different mentality than what Beach and his ilk were thinking about in the 1870s, because the idea was always mass transit first. And it’s hard to say without the benefit of hindsight which technology is going to ultimately win.

If we can turn the conversation back to this period in New York history that I’m particularly fond of in terms of the simply laughable corruption in Boss Tweed…what was something that surprised you? What was a fact that you learned where you said to yourself, “I never in a million years thought that that was the way this played out.” Anything come to mind?

The thing that surprised me most about Tweed and the corruption was simply how transparent it was; he didn’t feel it necessary to hide it very much. Everybody knew it was going on. Again, he lives in a mansion on Fifth Avenue when he is the city streets commissioner. The fact that Tweed actually kept ledgers detailing all the payments that he was making, the kickbacks he was getting…that was his downfall eventually. He had promised the New York County Sheriff that he would pay him $30,000 for some expenses the sheriff had, and then apparently reneged on that. And that got the sheriff angry, and he got his hand on the ledgers.

Maybe I shouldn’t be surprised, but the people’s acceptance of Tweed’s corruption, that it was the cost of doing business in New York City, and if you could get a piece of the pie, more power to you. Tweed’s constituents admired him for the way he was so brash about accumulating wealth, again, in some ways similar to the to the, supporters of President Trump, and as I say it now, I guess I shouldn’t be surprised, but, it did surprise me how brazen the corruption was and how lackadaisical the public seemed to see seem to be about it.

It’s one of the parables that I like from this book that also rhymes with the current political climate with MAGA and President Trump. Is it that Boss Tweed’s undoing came from such a tiny kernel of happenstance in a lot of ways? When this guy O’Rourke became bookkeeper and suddenly he was like, “…oh, what’s this?” It was the same thing that we saw in the 1975 fiscal crisis in New York, when one bookkeeper at Chase Bank was finally like, “Wait a second, there’s no assets here.”

The takeaway that I have that gives me some hope from this book, which is a really cool thing that I think other readers will have, is that downfall is coming because it always has and it always will, and there’s no way to predict where it’s coming from, and there’s no way to predict who it’s going to be.

I’m reminded of this book that I read in graduate school called Normal Accidents, about the history of the Three Mile Island meltdown, it happened with eighteen small problems and not one big problem. It wasn’t, “Oh, the switch doesn’t work.” It was eighteen things happening at once: this guy felt sick, and this one switch had worked a million times before is stuck today, and the guy was in the bathroom or something along these lines. That’s where this next downfall is going to come from, and there’s no way to predict it.

I take your point, but I hadn’t really thought about New York and the ‘75 fiscal crisis. It made me think of Bernie Madoff and who was the guy who was up in Boston who to tried to replicate Madoff’s books, and he came back in ten minutes later and said, “It’s a pyramid scheme.” And he tried to convince the SEC for years to look into it. That struck me as similar: eventually, somebody will find out, and then eventually, people who need to know will find out.

Hopefully, the people in charge. Now, I use that word very loosely; the people who are feigning leadership at the top right are going to annoy the wrong people at some point. Bernie Madoff is a great example. Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos is another example. There are examples throughout history of these hucksters and it happens fast. And this is not different because of the scale. The recovery will take decades.

Things can change fast. History can change quicker than you think. In January of 1989, nobody thought the Berlin Wall was going anywhere. Nobody thought the Soviet Union was going anywhere. Things can change, and they can change fast.

History, broadly, is about one decision, one veto, one loss at a time. If Beach is able to convince one alderman or one senator or assemblyman that his plan was better than another plan and maybe we get the Broadway pneumatic tube up and down Broadway, and that’s the dominant technology instead of instead of electric or steam for awhile. Or maybe the Els [elevated metros] don’t come into play.

There’s very little happening in New York at that level of veracity at this point, but congestion pricing could implode tomorrow, and we have no idea [likely not, but it could]. We could strike something underground along 2nd Avenue and the Second Avenue Subway is indefinitely delayed or doesn’t ever finish. Maybe some state rep introduces a bill to either remove or cap the BQE and Brooklyn’s or Queens’ fortunes change instantaneously.

That’s what I want in my modern leaders and thinkers is the ability to be prepared by having their hands in lots of different ideas and by being prolific in their interests with a mind at work. Beach is such an interesting character to write about because, if not the Subway, he would have found something else to invent or something to build. He just collided with all these things happening at once, which is a very interesting story.

That’s why it was such a cool era because Beach’s day was during one of these times in New York History where there was a weird optimism that any problem could be fixed with an invention. I think there’s parallels today that any problem can be fixed with an app or artificial intelligence, that any problem can eventually be fixed by technology. Back then, though, the problems were more prosaic, right? How do we address it without having to labor over it for twenty hours? How do we move large, heavy, freight over long distances efficiently? It was an innovative time in history, and it was also a time that it freaked people out.

The changes that were occurring shockingly fast, especially after the Civil War, when the number of patents doubled in basically two years. Suddenly there are new inventions everywhere. And I think there’s a fear that people also have now about technology taking over our lives that people had one hundred and fifty years ago. For example, Edison invents the phonograph and he takes it to Alfred Beach to demonstrate it. But just the concept that your voice would survive after you died totally freaked people out. I can hear my mother’s voice fifteen years after she’s dead? That that was just astounding to people. You can understand the trepidation people had.

What can our current leaders learn from Beach’s story? What is the takeaway for our current MTA, using the Subway “wars” between 1860 and 1960? Do you have any thoughts here?

I don’t know if you’re following what’s going on in in Philadelphia with SEPTA, the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, constantly going to the legislature, trying to get funding. And I see exactly what was happening in 1868, ’69, 70 in New York State and New York City, that’s happening in Pennsylvania and Philadelphia right now.

One of the problems that anyone who proposed a mass transit plan for New York City had to overcome was the fact you had to get a charter from the state legislature, right? You had to get a charter from Albany, and you had to convince folks who would never use the system that this was a project worth their support. And I think in Beach’s case, he wasn’t able to overcome that obstacle completely. He did win two charters but not by margin sufficient to overcome the veto.

Sometimes that we must act in the best interests of regions and groups outside our core constituency is something that needs to be reinforced. Eventually, it came around, and American cities for a time had the most incredible rapid transit urban mass transit systems in the world. And if you see how mass transit systems are funded in other countries, you’ll see that the cost is spread much more widely than it is in the US. If Beach had succeeded, would New York City have this amazing system of pneumatic tube subways?

Electricity probably would have proven to be superior as a means of moving people. Building these fans at every station blowing down. Siemens was a genius. He figured out let’s just run the current through a rail. Talk about like, “Whoa, that’s crazy, man. How could we get the electricity to the motor?” That would have happened, but Beach had a role in that. Beach proved you could build a tunnel under Broadway, and it wouldn’t sink. The buildings wouldn’t collapse. A.T. Stewart’s dear Marble Palace wouldn’t fall into the gutter. He proved it was feasible. He proved it was doable.

It’s very unlikely that any modern Beach would be able to do any of what Afred did in private or in secret, especially in our surveillance state. But again, it’s the technology of its time and place. It’s more digital infrastructure that’s happening right in private and in secret now, which makes it a lot harder to see.

Any last thoughts here?

Yeah. Beach really deserves to be remembered. Not even so much for the tunnel as for his contributions to American inventors. For the fifty years that he was editor of Scientific American and the support he gave inventors, large and small, he’s best known for the work he did, of course, with Edison and, Morse and Bell but he would talk to anybody who walked into his office wanted advice.

The most amazing statistic of all is that of all the millions of patents that have been granted in the US. The Beach firm, which went out of business in 1948, still accounts for 1.6% of all patents, ever. A third of all patents in the second half of the nineteenth century went through Alfred Beach’s patent agency. The book is also my campaign to get Beach into the Inventors Hall of Fame.

That’s a good campaign. Your book makes a good case for it. The last page of your book talks about how he’s nominally remembered now for his contributions to education and for educating freed slaves during Reconstruction.

It’s one of the differences between the great industrialists and the robber barons of the nineteenth century. A lot of them, whether they felt compelled or coerced, did give a lot of their money away. And I think it would be nice to see a little bit more charitable giving from some of the multibillionaires today.

It was certainly cultural. There was this idea of shame built into polite society back then, and while they may not have felt it in business, they felt it everywhere else. It would be great to have the modern barons give back. It’s amazing to me that the Met in New York is ever scrounging for money, ever. It’s very confusing to me that we live in a city of billionaires and millionaires, and the biggest cultural institutions are still begging for money and not opening up the museum as a real central square.

Carnegie shot all the strikers, but he did give us a lot of good libraries, right?

Hold your nose and hope for the best.

That should be our national motto.

I gotta read this book!