'Zombies' and what Brightline got right in Florida 🧟🚆

Part Three: How to make high-speed rail a reality in the US

Climate Solutions // ISSUE #88 // HOTHOUSE 2.0

Now see the complete high-speed rail series here: Part One, Part Two, Part Three, and Final Installment.

Hello dear readers,

Before we begin, a special shout out to Marilyn Waite for sharing Hothouse’s high-speed rail series on LinkedIn last week. It was fun to see the reception there as well as some very active conversations in r/urbanplanning following the last issue, which introduced the “ographies+” and the wider international context of the pursuit of HSR.

After last issue’s trip around the world, today our writer Sam takes us on a tour of what’s brewing HSR-wise here in the United States.

Let’s dig in,

Editor-in-Chief

‘Zombie projects’ and other domestic examples

By Sam Sklar

Now that we’ve got context and history from Part One and a frame through which to understand the high-speed rail problem from Part Two, let’s look at some examples of projects in the United States.

We’ll first consider “zombie projects”, like California High-Speed Rail and Texas Central, which are largely stalled, mired in the challenge of overcoming their own ographies+. We’ll then look at what Brightline got right in Florida, as well as how it is adapting those lessons to prepare for its next ambitious venture: Brightline West, of Southern California-Nevada fame.

First, the ‘Zombies’

As a reminder, when we’re talking about HSR, we’re looking at it through the following seven challenges‚ or ographies+:

Demography

Geography

Topography

Funding/Financing

Politics

Ownership

Connectivity

The most successful projects solve for all of them and push through challenges, near- and far-term. Conversely, “zombies” are contemporary HSR projects in the U.S. that have one or more ographies+ unresolved. They’re largely left in limbo as a result. Let’s take a look.

Zombie Project: California High-Speed Rail

A one-hundred-billion-dollar boondoggle

We can’t keep operating 31 flights a day between San Francisco and Los Angeles and expect to live in a world with clean air.

Phase One of the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA, the “Authority”)1—which hopes to connect San Francisco and L.A.—could slash those daily flights. Phase Two would branch the rail north to Sacramento and south and east to San Diego and the Inland Empire—all at a maximum speed of 220mph. But the CHSRA is struggling to make headway because it can’t overcome its specific ographies+, including a huge topography challenge and a very visible funding/financing problem.

Since its conception in the mid-1990s, the all-in price tag for CHSR has ballooned from $25 billion in 1999 to $128 billion in 2023. That’s a 412% increase.2 Despite the drip drip drip of public cash into the project already, there's no rail to ride and very little track-in-ground to show as of October 2023. That makes it really, really hard to keep public support and political will to fight for this project, even if (when) the project’s benefits (environmental, access, safety, time savings, etc.) will dwarf its costs (construction and operation) in the long, long run.3

Because of the hot debate—argued in good faith—along with legitimate criticisms of the project,4 it’ll be surprising if the CHSR is built before the actual, imminent glacial meltdown. To begin to understand why, let’s pass the project through the lens of the ographies+ weighing most heavily on it:

Topography:

Unlike Florida, America’s flattest state, California’s got peaks. The cost to tunnel through mountains is astronomical: up to $900 million per mile.5 Hopefully, new tech and economies of scale can bring this cost down or we’re in big trouble. An alternative? Curve the tracks around the mountains, which brings a whole suite of other problems with it, like the rail literally falling into the Pacific Ocean.6

Geography + Demography:

If CHSR were to veer away from the mountains, it would cross through several population centers along the coast (or, further inland, on a flat desert). Either option would force the alignment away from the ideal path connecting as many population centers (demography) as possible.

Funding/Financing:

It’s not that we, as a nation, don’t have the money to build the CHSR. The issue is how the money flows. Since the project is 100%—or nearly 100%—publicly financed, the Authority must follow hyper-specific state and federal rules. The rules are supposed guardrails against corruption and waste. But, in practice, as the 12-figure project demonstrates, with a drawn-out, expensive public process, any unanticipated construction contingencies can totally devour the project’s “reserve” budget alone.7

Politics:

This is probably the single most influential, if not nebulously defined, reason we don’t have a working HSR linking Northern and Southern California. Decisions at the city level can determine if the Authority can buy land to place rail or stations here or there. Powerful local interests sway statewide political behavior, too. According to the Times: “There was heavy lobbying by Silicon Valley business interests and the city of San Jose, which saw the line as an economic boon and a link to lower cost housing in the Central Valley for tech employees. They argued for routing the train over the much higher Pacheco Pass — which would require 15 miles of expensive tunnels.”

So instead of the simplest route—one approved by rail engineers back in 1999—there are now forks, doglegs, left-turns, tunnels, and viaducts planned where there otherwise didn’t need to be. Even still, even accounting for horse-trading, bad actors, poor timing, and self-serving interests, there’s nothing to show for the billions of dollars invested. There’s also no unifying narrative because there’s no unifying interest; at least no one’s really made a compelling public case that brings all the different players to the table. The state of California should simply grant the Authority near-absolute eminent domain to buy land and absolute routing privileges. This could help expedite the completion of sections like the “Central Valley, which quickly became a quagmire,” per the Times article. “The need for land has quadrupled to more than 2,000 parcels, the largest land take in modern state history, and is still not complete. In many cases, the seizures have involved bitter litigation against well-resourced farmers, whose fields were being split diagonally.”

The cumulative result? Stalled work. Delay is an effective tactic in American politics, known to keep projects in development hell for years. It’s relatively cheap, too, as the cost of doing nothing is always cheaper than forcing your opponent to defend against atrophy.

Of course, delays and funding shortfalls don’t look particularly good to a starving public. Even the most supportive politicians and local advocates will face growing resistance as inertia creeps. The best remedy is results, but, with no money, there is no groundbreaking or rail to ride.

Zombie Project: Texas Central

Texas Central is dead. Long live Texas Central.

The goal in Texas is similar to the goal in California and, unsurprisingly, similar to almost every other HSR project: access and mobility by any means other than single-occupancy vehicles or by plane. Being a direct link between Dallas and Houston, the benefit of the Texas Central Railroad to the region is obvious: cut a 3.5-hour trip by up to 2 hours. But with construction billed at $30 billion and growing, the cost-to-benefit ratio continues to shrink.

The top two pressing ographies+ plaguing HSR in Texas are ownership and politics.

Ownership:

There doesn’t seem to be any obvious benefit to sole private ownership here like in Florida, and, through years of development ups and downs, including the resignation of its CEO of six years in June 2022, Texas Central emerged in August 2023 in talks with Amtrak to study the corridor together. It’s unclear if the project is to move forward whether this would be as a Texas Central project with Amtrak support, or as an Amtrak project with Texas Central operations. Both arrangements have benefits and challenges. Amtrak has a history of partnering with local and state organizations to build the strongest networks possible; with such an arrangement, Texas Central could be a modern jewel in Texas’ transportation crown.

Politics/Connectivity:

The private ownership comparisons mostly end with the source of the funds, too: the federal Surface Transportation Board (STB) has ruled that, though it would be owned and operated by private interests, unlike Brightline, Texas Central is subject to STB oversight precisely because it’s part of the interstate rail network. The idea is that Texas Central can’t operate totally independently because there is an existing Amtrak service that it has to coordinate with—unlike Brightline, which doesn’t have this problem.

The result? Amtrak and Texas Central will continue to study the corridor’s viability and hopefully announce new funding for a plan and construction soon—or a determination that the project be shelved indefinitely. Either outcome is better than the limbo it currently sits in.

Brightline

What Brightline got right in Florida

How the Sunshine State learned to stop worrying and love the train

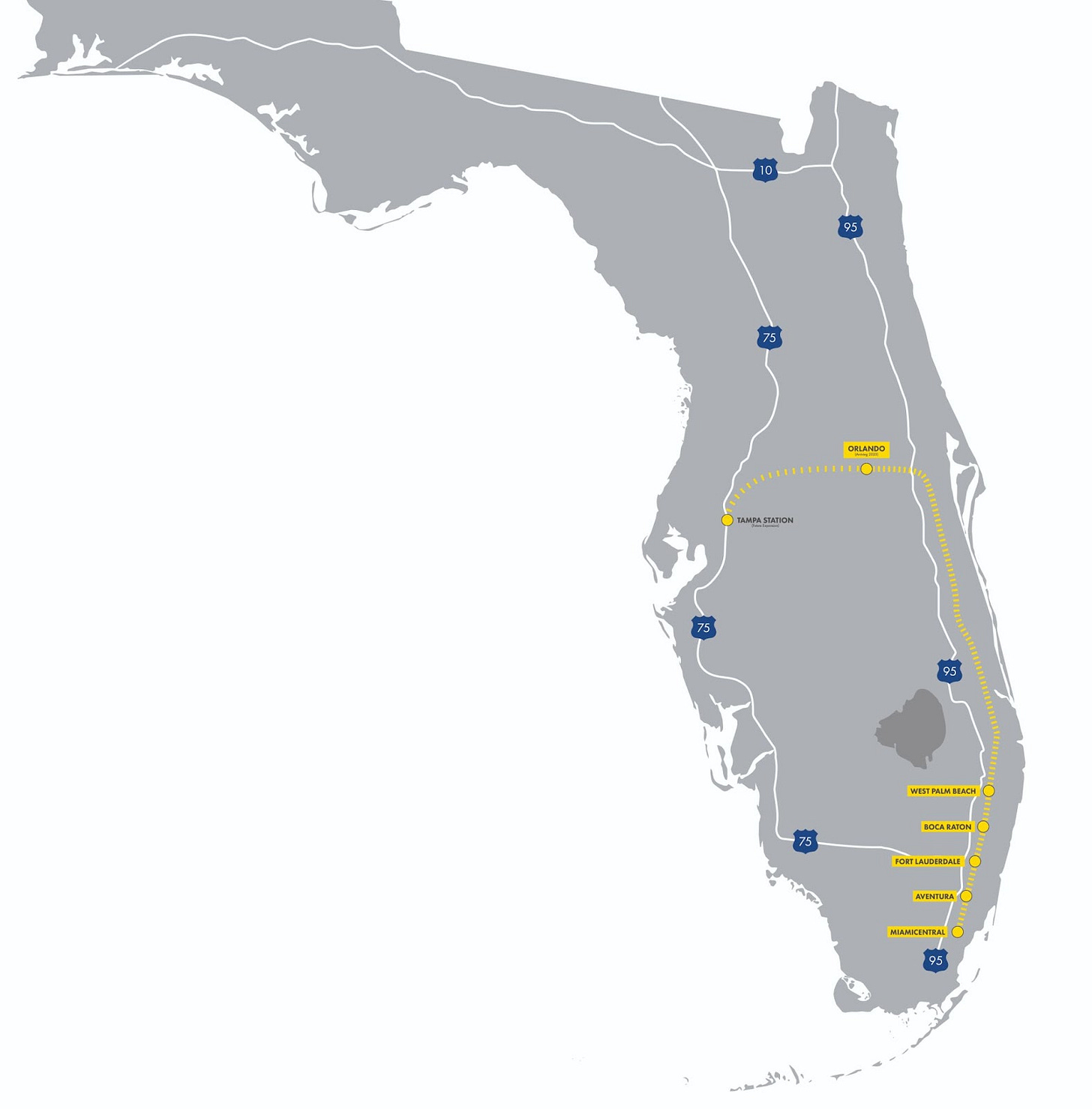

Last month, Brightline, Florida’s new-ish, privately-operated rail service, officially opened its long-anticipated Phase Two extension from West Palm Beach on September 22. Passengers can now make an uninterrupted journey from Orlando to Miami without leaving their seats or worrying about traffic. This is a bright spot in the U.S.’s rail renaissance. More trains equal more climate goodness and more access to opportunity.

Phase Three ultimately aspires to connect Orlando to Tampa (see map below), completing the intra-Florida rail project. Phase Three seems feasible only because Brightline’s investors and builders have demonstrated building rail in the U.S. is not only possible, but profitable.

Let’s look at Brightline’s success through the lens of our ographies+. Brightline hasn’t solved for all of them, but it’s come close. Let’s take a look.

Funding/Financing, Politics, + Ownership:

Brightline’s private ownership group found a way around and through political roadblocks, harnessing favorable support (or indifference) from legislators. The engineers built the rail alignment on privately owned or leased land. All of these decisions were and continue to be made in the pursuit of profit; hopefully, Brightline can continue to provide excellent, consistent, high-quality train service as a for-profit company for many years to come.

Connectivity:

To start and complete a successful rail journey, Brightline connects directly to local public transit, like Palm Tran in West Palm Beach and to Miami-Dade Transit. It now also connects to multiple transit options via the Orlando Airport, including Shared Connect Shuttle and a collaboration with Avis to seamlessly book a car to complete your trip.89

Topography + Geography:

Florida’s land is famously flat, but sea-level rise is an ever-increasing concern, so much of Brightline’s rail is on raised platforms. This increases the cost but makes the rail able to withstand longer-term sea-level rise. This is often the cost-vs-climate prep tradeoff in climate-affected areas. It should also be noted that the cities Brightline Florida connects are relatively close.

Demography:

Orlando is the fourth most densely populated city in Florida,10 plus the station connects directly to the Orlando Airport—the eighth busiest in the country—plus there’s a huge market given the access to two massive theme parks: Disney and Sea World.

Brightline West

Success begets success

Last of the examples, let’s look at how Brightline West is already poised to be more successful than its “zombie” counterparts introduced above:

Brightline’s team has shown competence building in Florida. The company is now simply leveraging what it’s learned to build Brightline West, a line from L.A. to Las Vegas. We’ll see—it’s a whole different contextual ballgame than the Sunshine State (including the challenge of wrangling bilateral cooperation between California and Nevada).11

Here’s good news: in late June 2023, the company received $25 million for station developments at Hesperia and Victor Valley, money authorized in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.12 The route, below, is scheduled to open in 2027, in time for the 2028 Los Angeles-hosted Summer Olympics.

Let’s apply the ographies+ to evaluate Brightline West:

Geography:

Los Angeles is, on a good day, about a four-hour drive from Las Vegas. The 270-mile trip is at a reasonable scale for rail to work. There’s vastness in this stretch of the American Southwest, but it’s not insurmountable.

Topography:

The tracks would be laid on mostly flat desert. Where there are mountains, there’s no overwhelming mountain to tunnel through; where there are rivers, there’s no insurmountable ford.

Demography:

L.A. is America’s second largest city, and, despite its reputation, is relatively dense and can certainly support high-speed rail. Meanwhile, Las Vegas is the U.S.’s 23rd biggest city. Its permanent population is comparable to that of Boston or DC. The hope is that the direct rail link will make the scorching desert heat bearable for more people to travel through.

Funding/Financing:

Like its eastern counterpart, Brightline West will rely on private funding sources, but will also likely seek additional federal grant funding to accelerate the building process.

Politics:

Here’s where Brightline West’s development might get tricky. Unlike Brightline Florida, this route will cross state lines, which makes a huge difference because interstate commerce falls under the jurisdiction of the federal government to arbitrate and regulate how these states do business with one another.

Ownership/Power:

Also like Brightline Florida, this rail alignment will be privately owned, which means that, ultimately, it will be up to Brightline if and when this Western rail system counterpart opens, how often it’ll run, and how much a trip will cost. There are currently $40, 90-minute flights between the two hubs. We must solve for this. We, as a society, will likely need to accept state subsidies if we’re to meaningfully address climate change.

Connectivity:

Brightline West will connect to California Metrolink regional rail for a 2-hour-and-10-minute, two-seat ride. The focus here will be on connectivity to Los Angeles. Las Vegas doesn’t have a metro system or rail, and its bus system isn’t robust, though it exists. Right now, the train is planned to end at Rancho Cucamonga, where there’s a slower connection to L.A.’s Union Station. In short, someone—whether it’s Brightline West, Metrolink, or both—could and should cooperate to eliminate the transfer.

The thorn in this project is the uncertainty that swirls around interstate-ness. Otherwise, let’s buy it and build and get people moving Southwesterly.

The real power of a successful Brightline West lies deeper, though, and is twofold: First, there’s the recentering of Las Vegas as a powerful hub for new commerce and pleasure travel: Phoenix to Las Vegas is in play; as is Northern California to Las Vegas; Salt Lake City to Las Vegas also becomes a no-brainer. The floodgates can open. It would also be tangible proof that high-speed rail in California is buildable and that a connection to the “zombie” project—California High-Speed Rail—is worth the investment. Even if it takes decades.

Next time

In the next installment, we’ll talk briefly about contemporary political affairs surrounding rail and, finally, to close out this series, address what you can do to support high-speed rail development in the U.S.

See you all in two weeks.

Hothouse is a climate action newsletter edited by Cadence Bambenek, with copy-editing by Peter Guy Witzig this issue. We rely on readers to support us, and everything we publish is free to read. Follow us on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Thank you to the readers, paying subscribers, and partners who believe in our mission. We couldn’t do this work without you.

More information from the authority itself, including economic and environmental benefits, as well as the current progress of design and construction may be found here.

Think 100+ years if our planet still exists.

There’s also criticism argued in bad faith, which you can find if you look hard enough for it.

Knowing that there will be a steady, uninterrupted flow of capital lessens project risk, which in turn lowers the discount rate and increases the net present value of the project—it’s therefore more sensical to invest a dollar into the project sooner rather than later.

Do we think that California will be thrilled to allow another entity to build new rail before CHSR runs its first trains? Yes—it will demonstrate local proof of concept and reinvigorate excitement for HSR. No—it will highlight the perceived calamity and delay that’s plagued the authority for nearly three decades. Here, in this essay, right now, we’re too far away to really see what’s going on.

Aka the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA)