A Review: The Transit Guy's Review of The Inter-borough Express (IBX)

Shining up the words and ideas of a great thinker and friend.

I’m going to get back to some original thought shortly, but first, some cross-promotion for my friend, The Transit Guy aka Hayden Clarkin, who has consistently put out thoughtful words and images about the state of our transportation and infrastructure. Follow him here to become a transit guy yourself, directly in your inbox.

I wanted to add some exasperation to Hayden’s most recent post, “A Review: The Inter-borough Express (IBX),” which you can read by following the linked title. I’m not going to summarize Hayden’s thoughts, but I am going to add some commentary to and expand on his most interesting takes, which I hope will lead to the next Substacker following my lead, and so on, until every single person has a fresh take on a potentially life-altering project for so many New Yorkers. I’ll break down my thoughts into digestable categories, but please read Hayden’s whole piece for context. It took me under 10 minutes.

Structure of this post.

Alignment & Challenges: I’ll take a deep look at the IBX’s chosen alignment and Hayden’s insights.

Mode Choice: I’ll expand more about the implications of the ultimate light rail choice.

Meta-thoughts and Thinking Ahead: I’ll contextualize Hayden’s thoughts about the Pros/Cons/Futurethink of the IBX.

Alignment & Challenges

Here’s what we know: Brooklyn and Queens are large enough (land area, population, population density, economic activity) to each be its own fully autonomous city, which Hayden points out. The massive issue—plus Manhattan looming across the East River—isreliable and redundant connectivity. This is essential for a city to feel woven into itself, expressly when the other option is a private motor vehicle, which has, dear reader, unlimited benefit if the driver or passenger is unbothered by cost, exhaust, and time lost. Knowing that there’s another option, automoatically and heuristically, that’s reliable and immediate is the whole ballgame for accessibility.

Over a hundred years of patchwork bus and bus network redesigns and a flimsy G train (whose service receded from Forest Hills, first in 2001 and then permanently in 2010)1 that “connects” Brooklyn to Queens the same way a carribbeaner connects my keys to my pants. The reshuffling of rail to outer Queens in the ‘00s has left much to be desired in terms of that overwhelming capacity—to the tune of 115,000+ Queens/Brooklyn daily riders who would otherwise a) drive, b) walk or bike to a nearby station, c) take an inconvenient ride into Manhattan and back out to their destination. The current alignment is inefficent, for sure, and the ridership, even as it grows will pale in comparison to established Subway Lines.

But that’s not the point—understanding “ridership” is complex and has multiple endogenous relationships (ridership affects access affects ridership, etc.) and shouldn’t be isolated. The true power of the alignment, which will run from Roosevelt Avenue in Central Queens to the Brooklyn Army Terminal in South Brooklyn, is how it shrinks the City and allows for circumferential travel between boroughs; this investment—somwhere between $4 billion and $8 billion2—and I cannot reiterate enough that this is an investment in public works—demonstrates the committment of an old state (State) to rethink who it works for. We would see an explosion of development and a reorganization of space by private and public actors.

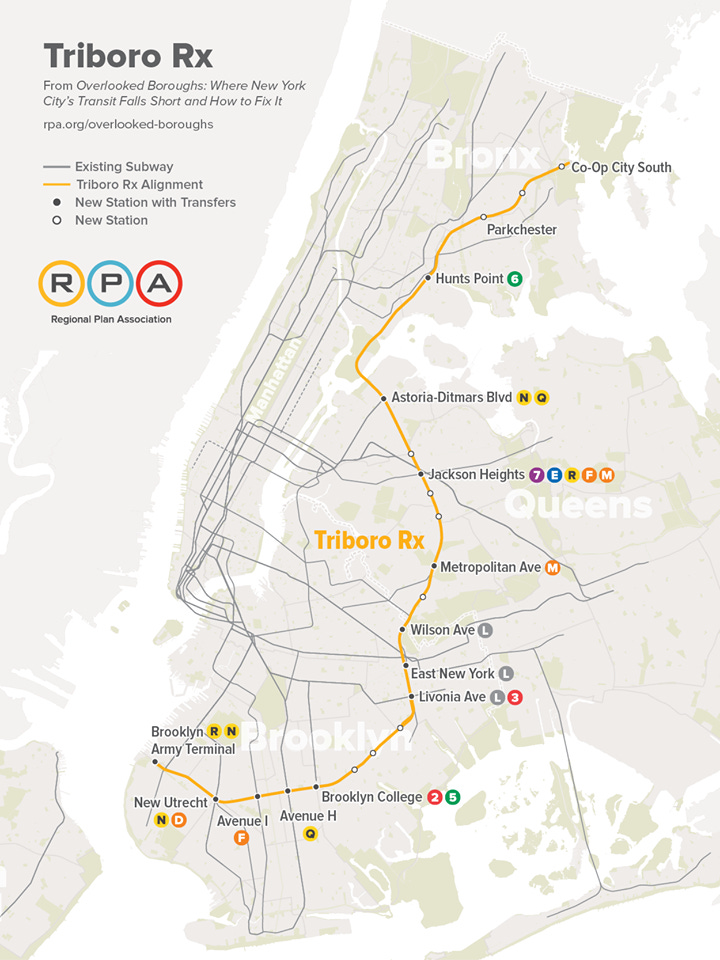

Speaking of: Hayden also makes a strong case against the current alignment—insisting that it can and should be extended to the Bronx across the Hell Gate Bridge at a minimum3, and that terminating this alignment at Roosevelt Avenue in Queens leaves multiples of accessibility unaccounted for—including access to Astoria, Hunts Point (where there’s new access coming via Metro North to Penn Station!), and beyond, all the way to Co-Op City in Northeast Bronx. I’ll reprint the map developed by the Regional Plan Association and included in Hayden’s post for context.

The redundancies are abound—and my additional question, in true policy form, is in two parts:

Is the chosen length—from Brooklyn Army Terminal to Jackson Heights—correct? How do we measure whether it’s right or not? Is there political will or can it be organized if not?

→ My answer mirrors Hayden’s—a hard maybe. It would be worthwhile (and I hope the chosen pre-design consultants look into this) to understand the marginal cost/benefit of extending the IBX before ground breaks and after to the Bronx.4

Is the alignment right? Is Jackson Heights the right terminus—and does the service “belly” enough to capture riders.

→ Simply, yes. Outside some ridiculous local fights about vertical alignment (above, at, or below grade), which the MTA will win if they want, the width for the path and some rail, mostly already exists, dramatically cutting fights and protracted legal battles with NIMBYs and other people who are wrong.

Mode Choice

Hayden shines in his analysis of mode choice—the type of vehicle that will ultimately move people from Brooklyn to Queens and back.

BRT, while more inexpensive (who is spending $4 billion on BRT?) does not adequately solve the technical or socio-economic problem the alignment seeks to: moving people, quickly without entering Manhattan—or traffic. BRT for IBX faces a very real capacity edge problem, as Hayden points out, but I’m concerned that what could be explored further is simply adding more buses to account for the gap in demand. Does BRT run into a geometry problem i.e. literally not enough asphalt to carry the BRT, traditional car (autonomous???) traffic, bikes, trucks, people, curb use, etc.? Is it a supply chain issue of actually buidling buses and delivering them on time? I’d love to run this exercise and have those conversations. It’s capacity building for the MTA to understand its pain points, publicly.

Heavy rail, sometimes abbreviated HRT, traditional Subway (or Elevateds), is another interesting option Hayden accurately and incisively explores. The MTA knows5 how to run this mode, it has a higher capacity-growth multiple, and could fully integrate into the current system.6 The problem is that the MTA can no longer simply dig up the ground and plop a functioning rail alignment into the ground and pile dirt back on top (also known as trench-and-cover), and the environmental and dollar expense of futzing a Subway that could integrate into the already variable loading gauge is simply too high. This project, rightly, is not a “Subway” or elevated rail line—it’s in fact something completely different.

Which leaves light rail, sometimes abbreviated LRT,7 as the chosen and best option. It’s the most flexible option, demonstrates commitment to the existing infrastructure, most cost-conscious, and has the ability to expand should ridership increase, slower than HRT/Subway, but faster than dead-on-arrival BRT. I really appreciated Hayden’s insight on labor and operating costs for this option, which he rightly points out, the MTA doesn’t currently operate, nor, really ever has. There will be redundancies, but I see these challenges as loss leaders, building state capacity to manage expansions/retrofits in the future.

Final word here is that LRT is the highest-and-best mode for the conditions sought in the alignment and that we should look toward Hayden’s interpretations as nearly totally correct.

Meta-thoughts and Thinking Ahead

Let’s go one-by-one through Hayden’s thoughts and make them slightly more exasperated.

PROS

The alignment is excellent. Agreed and agreed about the freight warning. Historically, freight railroads don’t proffer any train time to passenger railroads as a matter of practice, and there is no real way to force them to. All (most) disagreements are mediated/arbitrated through the Surface Transportation Board, who will issue non-binding resolutions to “compromise” among competing interests along a rail alignment. Without a way to force the freights to comply, passenger railroads, including and especially Amtrak, often rely on public pressure (near none) and non-exhaustive, de minimis service. The endogenous spiral is there (ridership begets revenue, which begets service expansion, which begets ridership, etc.) but the downwad spiral is also there—loss of alignment kills revenue, which kills ridership, which kills demand—and crucially public sentiment. It is completely possible the freight rail (CSX owns the northern portion of the proposed alignment) is uncooperative in any number of ways and bloats this project’s budget and timeline simply because it can.

I expect that CSX will, eventually, gladly accept a piece of the farebox or availability payment for the pleasure of suffering through a partnership. Keep your eye on it.

Far easier to build. Agree, 90% practically, but 10% fear some hiccup along the way or unintended problem makes this project a boondoggle. I am hopeful the predesign consultants raise these issues right now.

Strong bus connectivity. Yep and there’s an interesting case to study here re: “free buses” and a finished IBX alignment. Are the buses more shuttles than full lines? This feels like the right place to talk about fare and fare restructuring. To make the IBX fully integrated into the system, the MTA should charge a Subway/bus fare equivalent (likely >$3 in 2025$, which could balloon to more before the line opens for passengers) to demonstrate that this mode is a public service and is intended to mirror intracity commute patterns and not intercity patterns, like Metro North Railroad or Long Island Rail Road8. I’d love to see a larger discussion about fare restructuring and OMNY integration past the current underwhelming use cases. The IBX discussion is the place to explore it. Let’s see it.

Housing/development potential. Strongly agree with Hayden and with the IBX Transit Cost Team on this complicated and obvious discussion about land use/transporation integration. This is an opportunity to point out that land use is local (City-driven), while the IBX is statewide (the MTA controls transit capital and operating spending). We can’t even get real bus enforcement or built bus lanes in any sort of meaningful way, so I have less hope that a transit project will spur a massive rezoning operation, but I’m curious to see how City Charter Amendments fare in the upcoming citywide election in November 2025. Not only would we see a change in land use process, but we might get a stated preference poll in realtime about New Yorkers’ feeling toward building an absolute, metric f*ckton of housing while the IBX is under construction.

CONS

Now onto Hayden’s insights into the IBX’s negatives:

The Bronx problem. I’ve addressed this above, but Hayden makes some more interesting, technical points in his article.

It’s light rail. Also addressed above. Light rail is a short-term solution for growing transit demand. There’s a reason our Subways are heavy rail.

Mediocre major station connections. This point I cannot make strongly enough so I will lean into it more than Hayden does: without a fully integrated connection, this project loses much of its appeal. We are not building a new rail line—we are building capacity and access into existing infrastructure and for every foot the stations/platforms are away from each other, public sentiment and demand wanes, and fast. No one is thrilled about the 10 minute walk between the 8th Ave Line (A/C/E) and the 7th Ave Line (1/2/3) at Times Square, but it’s a relic of smushing two fully separate systems into the same system, so this feature is relatively overlooked as “bad,” and instead “good enough.”

We have the opportunity to look outward to Japan or Switzerland9 into building new stations as destinations in and of themselves to justify outrageous station costs—upwards of $100 million in some cases. These stations can, should, and must be centerpieces of neighborhood strategies for new housing, mixed-use, retail, commercial, or office development at unprecedented levels. They cannot, cannot be afterthoughts and out-of-station transfers that feel like this system is being plopped instead of integrated. Sure cost it out, but it’s worth it at double the price. Not every station has to look like Tokyo Station, below, but it sure does have to try. I will die on this hill.

Automation (or lack thereof). The rail line must take advantage of new technology, including and centering on automation. It’s on a fixed guideway (the rail/gauge itself) and its consists (fancy word for train cars) will likely be brand new and outfitted with required technology for automation. I expect the TWU Local 100 (the local transit workers’ union) will have much to say about this, but it’s also then time for our MTA leadership to test their mettle, while fighting for low-cost fare integration (see above), which is only tenable via dedicated tax, or elimination of a huge cost in operating these trains. Hayden points out this labor force doesn’t exist yet and isn’t unionized yet; the staff hired to run these trains should be unionized (I fully support labor and the right to collectively organize). But our rail program isn’t separately a jobs program and not automating this system will add a huge operating expense that should instead be passed along to riders as savings.

Odds’n’Ends

Hayden says:

Outside of a crosstown Bronx line (an argument for another day), I can’t think of a single project NYC needs more. To put it in perspective, IBX would move as many people as the entire Honolulu rail system.

I argue that the Queenslink Project is a project that NYC needs at least as much as a crosstown Bronx line, if not more.10 A fully executed IBX only enhances this case, as there are a ton of similarites between the two projects’ philosophies, if not their conditions and ridership capabilities. The MTA must make sure to internalize findings from the design and development of IBX to apply to its capital program going forward, deepening even further its internal capacity and demonstrating to its owners—New Yorkers—that it is capable of operationalizing a not-so-small-amount of billions of dollars to help us get around this place we call home a little easier.

The IBX is also an opportunity to explore electrification, level boarding, caternary (overhead) A/C power, and other points excellently made by Nolan Hicks in his Momentum report. Proof of concept in the pudding. For more on that: see my review of this truly awesome report.

Last point and thanks for reading this (go read Hayden’s work and follow him everywhere): the MTA can demonstrate exactly where Congestion Pricing dollars are going, especially to riders who feel put upon by a state revenue enhancement11 without adequate and/or overwhelming service to replace a car trip to work, school, services, or joy. The organization has a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to redefine how it communicates and engages with its riders (and future riders!) so that this project feels of the people and put the “I” in IBX.

Hayden has an excellent comparision table that we’ll get to in the next section, but the investment works out to under $100 per daily rider. See?

If it is indeed rail and not bus—more on that in a minute.

Sneaky Hayden mentions “Staten Island” like this project is going to tunnel under the Hudson Bay. But could it?

Theoretically and mostly practically.

What would it’s shorthand call-sign be? The “I” sounds too much like the word “eye,” so that’s a no. I like the “X.” It sounds mysterious, which is how I like my transit planning.

What’s the actual definitional difference between “heavy” and “light” rail? Capacity, vehicle technology, and acceleration/max speed for three—but as a rider there’s no real difference if the goal is to get from point A to point B. It is incumbent on the MTA to ensure this decision is explored and explained.

LOL these bozos can’t even decide and agree on how to spell railroad.

No big deal.

Disclosure! I’m on staff/volunteer with Queenslink, so I have a vested, not conflict of, interest in this statement.

A tax. At least it feels like a tax to people who aren’t directly seeing benefits of Congestion Pricing.