Exasperated Recommendations: Momentum and Rail Electrification

Let's Go Do It: Nolan Hicks' brilliant, comprehensive policy proposal captures the essence of deep work with a flair for accessibility-no pun intended.

Followers and readers, I come with a review of Nolan Hicks’ most recent publication for friend-of-EI Transit Costs Project called “Momentum,” sponsored and guided by Eric Goldwyn at NYU.

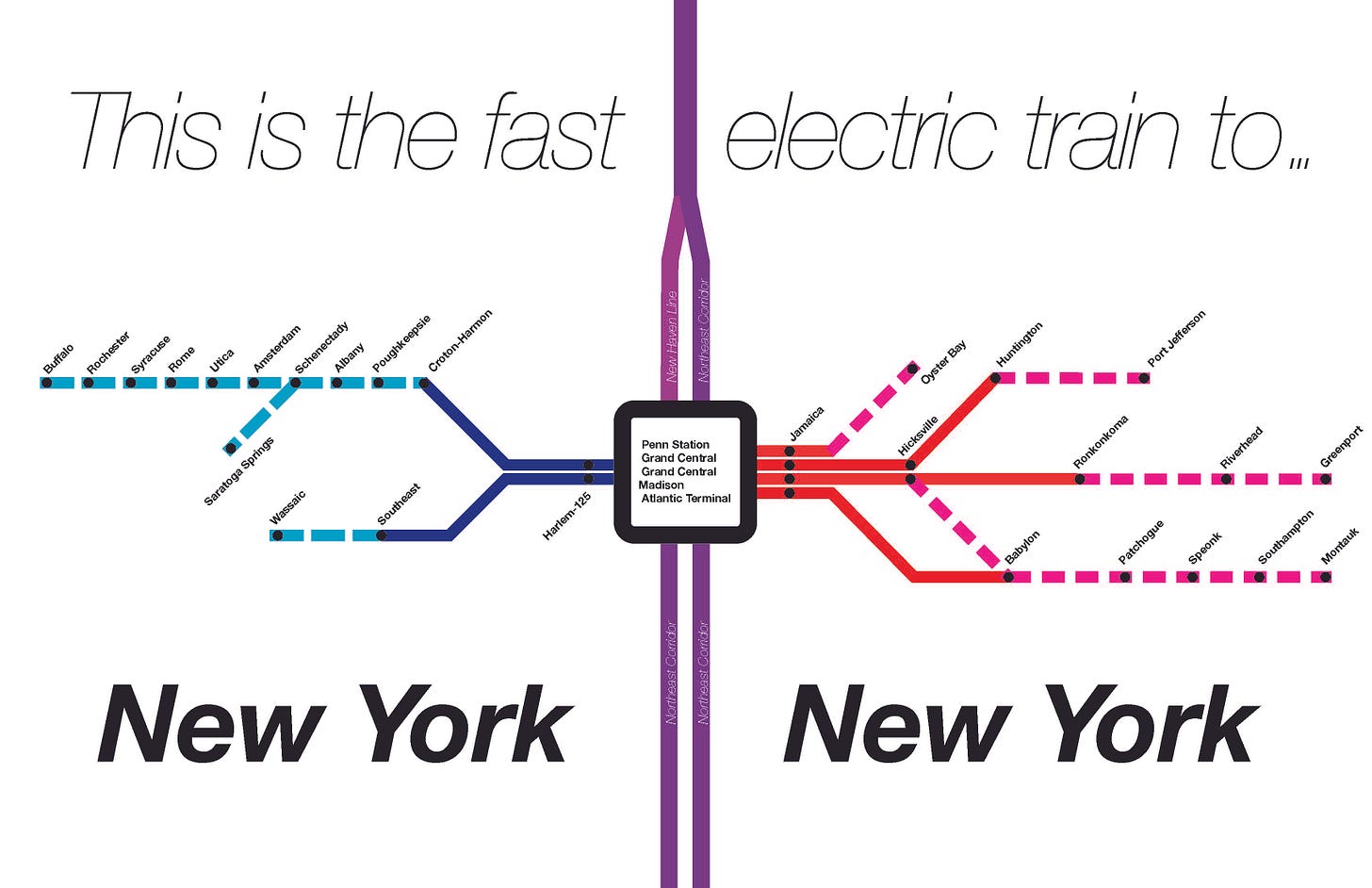

Others have written summaries and takeaways from Nolan’s report. I’ll direct you to Pedestrian Observations, Streetsblog NYC, and more, but really, you should take the hour to read the whole report if you’re even remotely interested in the future of travel in, around, and through New York. Instead, I’m going to dig into the how and why of this document—to dissect its bona fides and what makes it work as a brief but also a challenging and worthwhile read. I exchanged several messages with Nolan to help contextualize some of his thinking, much of which is lightly edited and pasted below. But first, some takeaways.

Momentum’s Momentum

There are four main reasons why Nolan’s Momentum continues to be eminently readable, rereadable, and relevant.

Candor, personality, and voice.

Data relevance, not dependence.

Reader-centered narrative arc.

Reality-checked solutions.

I actually think it’s fun that you, dear reader, follow my thought process—what I thought was interesting as I read this brief, and what I wanted to follow up with Nolan on. For example:

1. Candor, personality, and voice.

I can hear the resigned and determined tone in his first few paragraphs here. “The switch from transit to cars is proving far harder to tackle.” Yes, Nolan, no sh*t. “It’s simple physics.”1

Savings savings savings. Accessibility. Slashing trip times. “This makes commuter railroads an obvious candidate.” Reform is possible and it’s within grasp, but won’t anyone listen! Read on, intrepid self-selected railfan.

The transportation planning version of “If he wanted to, he would.” But it’s not snark, it’s straightforward: we can pay for this, we know how to pay for this, we should pay for this program, but again, we just lack the _____________2 to do it.

The whole report builds a story based on assertion <> evidence, but it’s written for an audience who should be reading it (legislators, advocates), not an audience that was going to be reading it (railfans).

2. Data Relevance, Not Dependence.

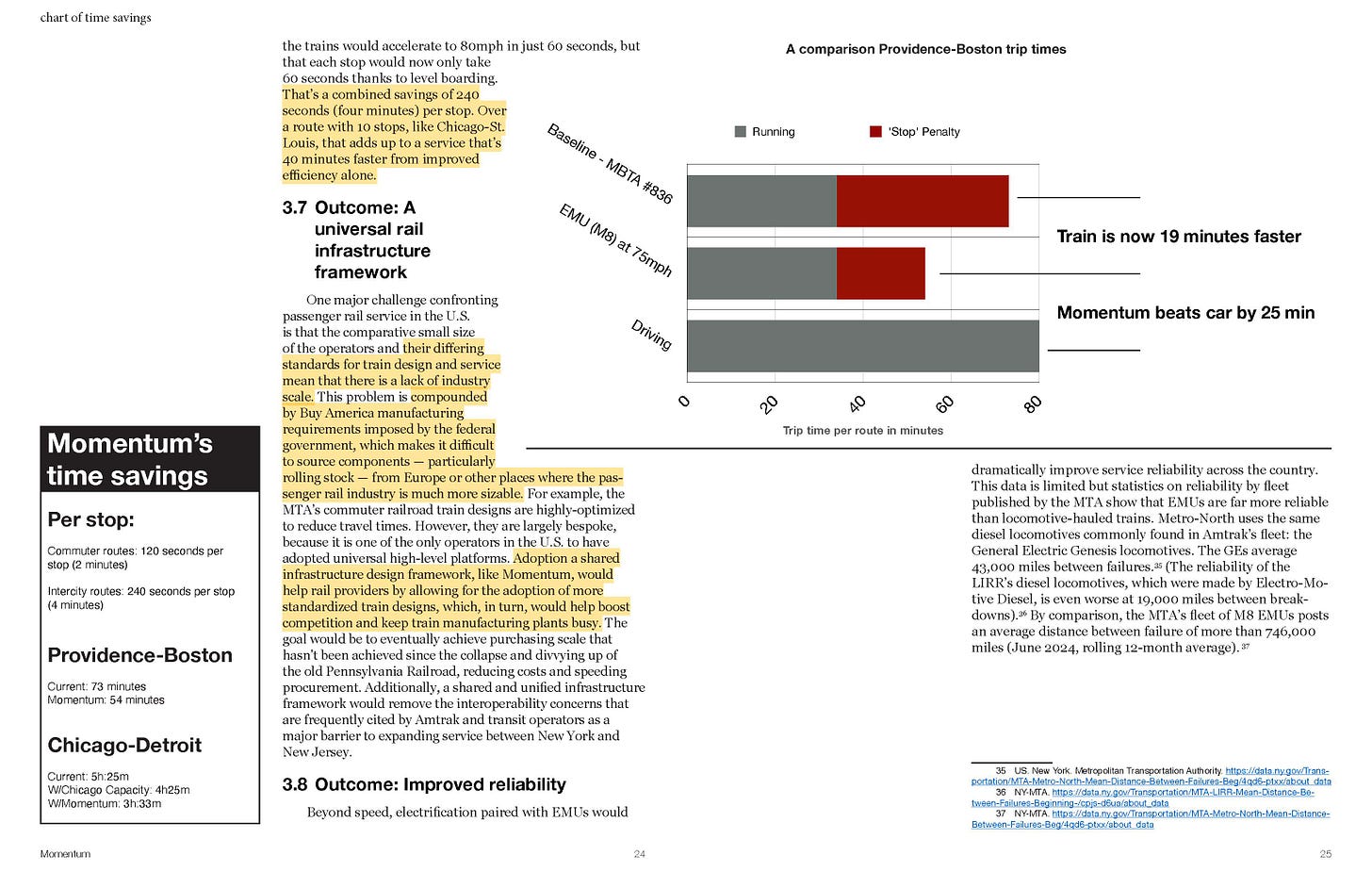

Nolan’s data boxes draw our attention to important facts and figures, which are also woven throughout the narrative. Momentum is not an exercise in data collection and budget decoding, but an excellent example of data-driven storytelling; the kind of paper your college professors beg you to write, and one we should expect our professionals to know how to.3

I didn’t highlight any specific data points throughout my read, but it was good to have them there as reference points—a savings of 120 seconds per stop is an incredibly powerful number that simply sits there to help propel the narrative. The more you think about how incredible this is—2 minutes times x number of stops, the real power dawns on you. The incredulity turns to obviousness and then exasperation (why you’re here) as to why this isn’t done.4

3. Reader-Centric, Narrative Arc.

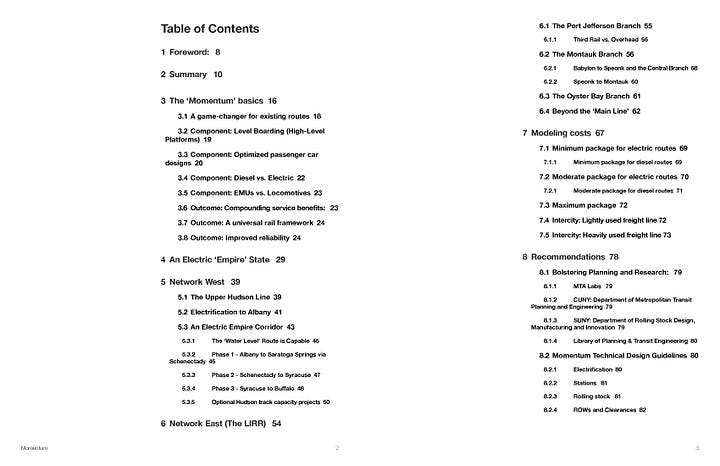

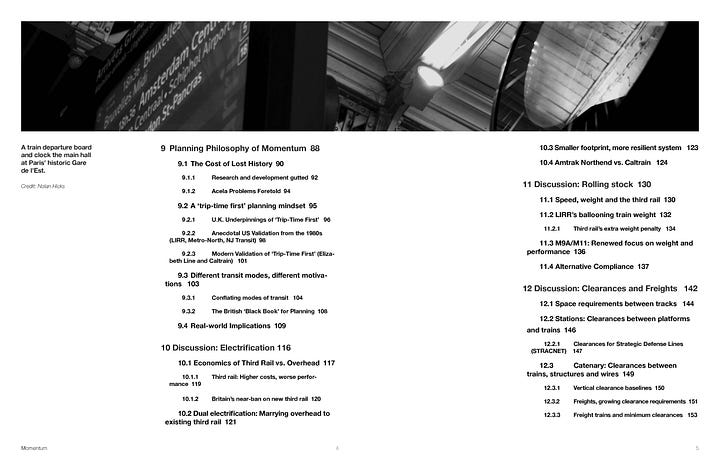

Nolan imagines how his reader would want to interact with Momentum. It’s written for someone who doesn’t even know there’s a problem, not just what the problem might be. The chapter list:

The first eight chapters are written for someone who’s sure not a planner (legislators! advocates! my own mom!). Let’s build to the problem; let’s use plain language; let’s talk in geographies readers would and could know or get to know; let’s bring the problem and multiple solutions together, with examples, graphics, maps, and ahas! and then lay it out in professional design software and put it out there. The reviews are positive. Sure, I have comments, but I’ve asked Nolan to answer them, which he’s done below.

4. Reality-Checked Solutions

Nolan, if you don’t know him (and I don’t personally, yet), is a tenured reporter and journalist. He’s not a career academic—not that there’s anything wrong with that—but it’s helpful for our policy to be written by people who’ve engaged with reality on a day-to-day basis. Each section of the regional system gets the attention it’s owed; Nolan’s storytelling doesn’t feel effortless either, but rather carefully curated and deeply connected to the thesis.

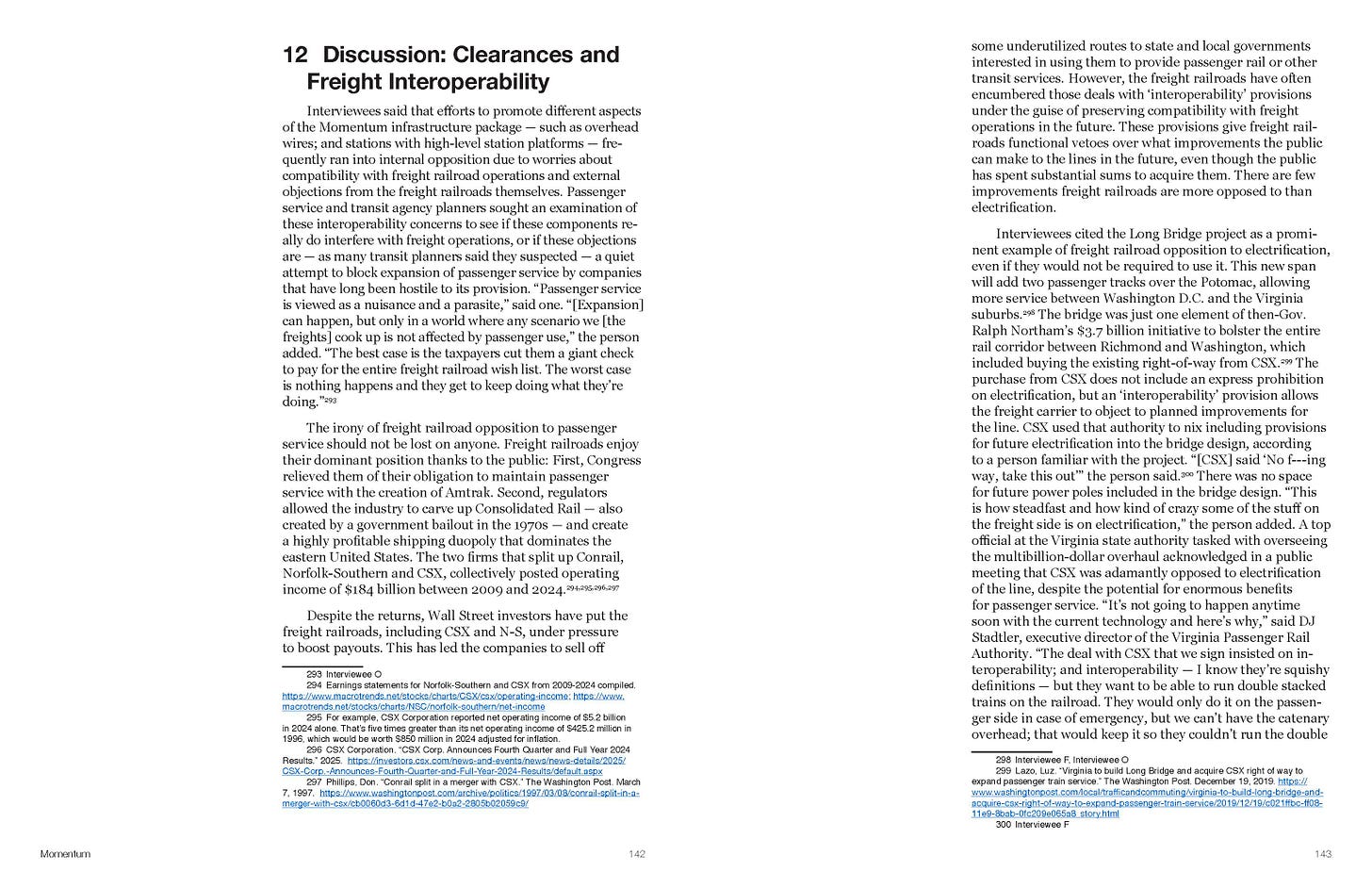

Momentum is back-ended by flavorful context, too. Nolan’s research is rooted in a historical context that’s ossifed so badly we have to have four chapters discussing why this, after having read this report, fairly obvious idea is stuck in the mud: Doctrine & History5, Electrification, Rolling Stock (the trains!), and a fairly arcane but important topic, Clearances.6 And of course, all of this momentum feels particularly inert in the face of constant and consistent logjamming from freight actors.

If this is your first tangent with rail research or transportation policy, the even tone with which Nolan engages the Class I freight railroads as they intersect with passenger rail. As of early 2025, there are six freight carriers that carried over $1 billion in goods, and they have an outsized power on passenger operations across the country, across the Northeast Corridor in places, and along some of the corridors shared by passengers and goods. Because they’re the owner/operator of at least part of the rail, they often try to dictate passenger operations…and often do.

But read on for more information. The freights7 are a huge deal in rail planning across the United States (and less Canada, and less Mexico) and could be a huge impediment to implementing Momentum. Nolan approaches this conflict matter-of-factly, and if there’s bias, it’s obfuscated by clarity and just damn good reporting and storytelling.

But Don’t Take It From Me…

Nolan was generous to answer some questions about the process of winning the opportunity to write, the planning of, and the effort it took to pull this report together over the course of about 10 months. Thanks again for engaging with me, Nolan. Hope to meet you in person soon!

Where did the idea come from to write this? Did you approach Eric Goldwyn at NYU’s Marron Center, or did Eric approach you?

It was an idea that I’d been noodling around with at The Post for a while. You can see a smidge of it in a story I did about substations and specs and costs on the Port Jefferson project. The Post is (or was?) very city-focused so a lot of the story ends up focusing on the IBX (now with a tunnel, which it didn’t have at the time). But that was kind of the start from a serious reporter perspective, and it was a bit of a crash course into the whys of electrification (faster service, better service, etc). After I got laid off, Eric approached me about finding a thing to do, and we jointly landed on electrification. He was interested in it as a missing part of the infrastructure conversation when it comes to improving US rail, as was I.

Why is this especially relevant now? Would it have been more relevant a number of years ago? Does your work provide a blueprint for the future—assuming rail technology only gets more efficient and the politics unclench a little—or can you foresee a time when there's a totally new paradigm?

In reverse order, second question: I really hope so. There’s been so much knowledge lost in American passenger rail planning over the last few decades because of a near-total federal divestment from research on this subject. You really have only started to see a few green shoots that were financed by the Biden Administration on electrification and in a few other places where traffic has become so untenable and space is so constrained, policy makers are forced to consider rail because of the sheer physics.

Basically, what we sought to do was to lay down a common framework—which is basically the NEC, MTA/Metropolitan framework—and apply it elsewhere to show that all this work that was done to modernize American railroading in the 1960s-1970s was fundamentally the right path and really did make a difference. I stumbled backwards into that realization (which was a head-slapping moment) at a whiteboard, just trying to sketch out what an infrastructure framework to maximize the benefits of electrification should look like. This led to breaking up routes into run-time vs. dead-time, realizing that even on medium-distance intercity routes, we lose tons of trip time to ‘dead time’, and trying to find ways to boost speeds by attacking that. If you can take a route rated for 110mph and get the average speed up from 60mph to 90mph, you’ve cut your trip times massively without having to eminent domain your way through cities. It’s not a new paradigm, it’s just picking up the thread that we lost when we stopped studying and planning this stuff.

First question: This tries to build a bridge between pokey diesel service that can’t run fast enough to generate ridership or make money, and gazillion-dollar HSR projects that take decades to get off the ground. Here’s a middle path that basically says, “Ok, fine, how we build huge things in this country is pretty broken; so why don’t we use as much of what we have as possible and see where we can end up?” Making rail viable and more financially secure at short and medium distances makes it a lot easier to build the ridership and the constituency for bigger projects down the line. Outside of New York, Philly, Boston, we really have to re-introduce rail to America as a thing that can be a part of your everyday life and a big point of that needs to be running at speeds and frequencies that are good enough, people will park a car and start taking the train again.

This all feels so obvious, but this work isn't sexy or shiny. Have you thought about how the MTA might campaign around this idea so that its priority makes the most sense? What goes first? What does success look like in the short, medium, and long term?

To the MTA’s credit, to William Ronan’s credit (a phrase that is not often typed), they got what a modern railroad should look like correct; and, they’ve rolled out to a far larger share of the metro population than anywhere else in the US. There were stories about a year ago (maybe more) where the transit commentariat was obsessing over these 100mph commuter rail lines in Asia, bending the physics of what urban and suburban can mean. That was the promise of the M1 when Ronan first ordered them in the late 1960s. The weak inherited third-rail power systems meant that the LIRR and what would become Metro-North could never deliver those speeds, but fundamentally, in terms of design and infrastructure framework—EMUs, high-level platforms, wide doors—the MTA not only got it right, they were basically developing the prototype for applying high-throughput design principles typically found on subways to traditional railroads. Maybe everyone else eventually gets there, but also maybe not.

Philly and Boston still have tons of low-level platforms. The MBTA also hasn’t electrified its service running underneath Amtrak’s wires. Part of what we wanted to do with this report was to really clearly illustrate how each one of these ideas, the framework we dubbed momentum, compounds and works in tandem to deliver faster service and more reliable service. We want to empower policymakers and transit agencies to be able to go out and ask better questions and deliver better projects.

—Rapid fire!—

How long did this take to research, write, and edit? The grant was awarded in June, I think; we published in very early April, so almost a year. I want to give a shout-out to Streetsblog NYC for being so accommodating in the home stretch.

What was the first part of this that you worked on? That’s a good question, and I don’t know that I have a great answer. I think it was trying to come up with a model for what electrification could mean—and then reading everything we could get our hands on to sanity-test that model.

What was the most astounding takeaway? That we knew this stuff and basically forgot it all because of these massive cuts to the R&D in the 1980s.

What was the first section to get cut/edited out? The ticking clock forced us to take a big ax to the case studies. You see a lot of the work in the costing models (Ch7), but we wanted to do case studies as detailed as the New York one for Chicago (Chicago-Detroit, Chicago-Grand Rapids, Chicago-St. Louis); New Jersey (Main/Bergen; M&E); Philadelphia (I’m low-key obsessed with Philly-Allentown and Philly-Reading), and DC-Richmond-Raleigh.

If I'm just learning about this for the first time, what's the biggest takeaway you'd want a non-technical audience to get from Momentum? That our existing rail lines can compete with a smart infrastructure framework. That we can have a European quality rail network, at least in the Northeast/VA and the Midwest. It might not be as sexy as the Eurostar moving at 180mph through France, but it’s buildable today using the routes we have today. Think about what a network of Northeast Corridors would mean for upstate communities like Albany, Syracuse, and Buffalo, or for midwest cities, like Chicago and Detroit, and St. Louis. We can do it. Let’s go do it.

No, it isn’t.

Insert: political will, basic math skills, understanding that the needs of constituents are the first and foremost thought, and that funding a future-ready, regional rail system would create one of the biggest economic boons, probably ever, for the New York Metropolitan region, upstate New York, and any and all economic actors who would ever interact with the region.

They sometimes do! And sometimes, uh, don’t.

There are lots more examples of relevant text boxes that support the narrative.

Curated to not make it a dissertation, but there’s so, so much more on this topic if you search for it.

Both height during travel and width, between tracks and between the platform and the train itself.

Sitcom-level stories of chicanery; if you know me, ask me about them. If you know any transportation planners, ask them about them.