R@nd@1 0'T00l3 wrote the single dumbest article I've ever read.

"A Global Leader in Obsolete Technology" is written for no one in particular, but that's not its problem. It lacks an attachment to reality in almost every sentence. Here's a few thousand words why.

There’s some argument over the origins of the adage, “Never argue with a man who buys ink by the barrel.” Some attribute it to William Greener, on of the United States’ first publicists in the 20s. Others swear they heard Indiana attorney and eventual governor, Roger Branigin, say it in the 60s. Was it noted polemicists Mark Twain or H.L. Mencken? Ben Franklin? Or can it be attributed to a dozen other people?

It doesn’t really matter of course who said it first, we’ll likely never know, and it’s fine that its origins are spread out: it means more people might hear it and use it to great effect. I’ll use it here when dissecting the following essay from ink’s greatest customer, self-described and monikered “antiplanner,” Randal O’Toole. He’s a Senior Fellow at the right-leaning, Cato Institute and has been against government intervention in the urban and rural planning spaces for almost 50 years.

I know that responding to his recent article—“A Global Leader in Obsolete Technology”—I’m fighting a losing battle. I’m not going to win over Mr. O’Toole with a reasoned argument. My squabble isn’t with him as a person; his arguments are not personal and not original. There’s always been a dark side of this Force that has run through government, that the government itself is the problem and if it would only get out of the way, market forces themselves would solve most of humanity’s problems. With people who “know what they’re doing” at the helm.

I want to make it clear that this issue applies to the left and the right. For as much as “trickle-down economics” is a sham, so too were (are) many of the “progressive” era reforms that dressed up its Faustian modernism as Good for all seasons. Both strains of thinking are bad. It’s how we got 164,000 miles of overbuilt highways to begin with.

Because while it might not matter the origins of lots of O’Toole’s arguments, they’re fundamentally flawed and allowing them to leak into well-meaning debate as equally thought-provoking and worthwhile distracts from actual good ideas; which is of course the entire goal of modern Republicanism, if there even is one to be found.

I know I’m getting into this with a ballpoint. Still, on we go.

I want to break down O’Toole’s article, critiquing both the content and the semantic style. It’s important to know the ways the article misrepresents the facts and the ways the language and argumentative style promote a particularly spiteful agenda.

Misrepresenting the Facts: Before we dive into the individual claims I want to address the strangeness of data and “truth.” First, data are only useful when they’re contextualized and rounded out with references to why they’re important. Simply isolating that something costs a large number of dollars or that a trendline is running negative alone does not tell a story, no matter how daunting the numbers seem. People have written books about this problem, data literacy in general, and I fear far to many planners (and antiplanners) still see data as the Shibboleth.

Language and Agenda: I’m sure the left does this trick, too, to promote its myriad agendas, but I notice that lots of right-leaning op-eds use TONS of adverbs to manipulate the tone of otherwise innocuous paragraphs or clauses. To those who don’t need persuasion—the target audience of lots of these posts—see this type of language as a big confirmation of their already Medusaed beliefs. To those who would need persuasion—a small audience of confused centrists—might not notice the round language.

So O’Toole’s article isn’t the single dumbest thing I’ve ever read because it’s rabble-rousing, it’s singularly insipid because it lacks an attachment to reality and honestly, if he were to have reworded the article randomly, it would have more germane impact and insight into modern transportation policy.

The “obsolete technology” to which he’s referring is…rail, which almost every developed country, except the United States, understands to be a pragmatic solution to moving masses of people from points to points.

He thinks the “solution” to our transportation problems is to continue to build more wide highways. He has not defined what problem he is trying to solve—or maybe he has, by accident: moving individual vehicles long distances, as fast as possible. Even if this is the case; even if the goal was to move as many motor vehicles around as fast as possible, the confluence of widening highways with every driver being aware that the highway has been widened, slows cars down.

He conflates “losing money” with “costing money.” This point is mostly moot, because his whole career has been built on deprioritizing government spending wherever possible, and the most cogent and despicable method to do this is regulatory capture—starving the beast.

I am unclear how O’Toole defines “success.” What does a successful future look like? For someone with decades of grand ideas for future technology, he seems to be Pollyannaish about a time period for successful accomplishments of …something by measuring …lane-miles of highway? Cars don’t have feelings.

His mathematics and data are cherry-picked to promote an obvious agenda. If you cherry-pick data and manipulate how you display them, you can say anything you want. It’s disingenuous, misleading, and completely part of this playbook.

His language is not meant to be explanatory or argumentative—it’s meant to be inflammatory and obtuse. It’s a trick of the faithless, who have nothing but ink to spend, to rouse rabbles.

Let’s go through these, one by one, using O’Toole’s own words, and see why this article is confusing and dangerous for progress in any direction, but especially toward rail planning and construction.

1. Rail is Not Obsolete.

The title itself assumes an outcome based on faulty logic. How does O’Toole frame his argument?

High-speed trains, in particular, were rendered obsolete in 1958, when Boeing introduced the 707 jetliner, which was twice as fast as the fastest trains today.

If travel were frictionless—if we could simply leave our place of residence/business and hop on a plane and land exactly where we needed to go—then this argument would make slightly more sense, all else equal. But all else is not equal. Several break-even points exist for almost every trip; it’s the basis for mode-choice analysis. We, as consumers and world-travelers, can choose which mode to take…

(…oh, wait no. Since lots of this country is spread waaaaaaaaay out, it makes no sense to compare an automobile trip to a train trip to a plane trip—these options simply don’t exist for folks in more rural communities. It’s not even comparing apples to oranges. Instead, it’s comparing apples to not having apples.)

…among a car, a bus, a train, a bike, walking, a boat, or a plane. We’re not going to take an airplane to the store, and we’re not going to walk to California from New York (usually). But we might choose to take a train or an airplane for medium-short to medium long trips, based on a number of factors, none of which besides cost and time, O’Toole figures into his analysis. A traveler might not want to fly for any number of reasons.

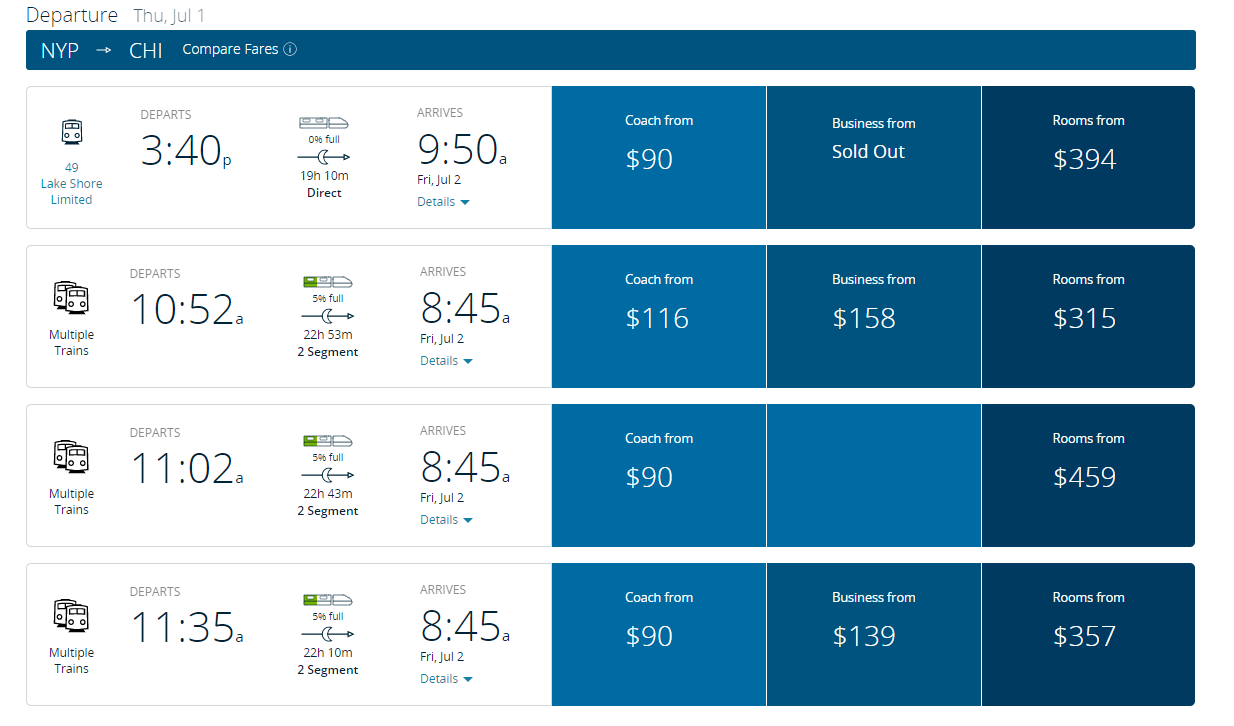

Let’s take a few examples starting with one that corroborates O’Toole’s point, to demonstrate the basest level of critical thinking. Here’s an Amtrak schedule from New York Penn to Chicago Union Stations on July 1, 2021.

Here’s a similar list of options to fly from LaGuardia Airport in Queens to Chicago O’Hare.

The cost difference is negligible but the time differential is substantial: it takes a full 20 hours more to travel to Chicago from New York by train. Aha! Says O’Toolian logic, must make high-speed rail irrelevant! It’s a blatant manipulation of inputs to bootstrap a point. This rail option isn’t even considered high-speed—it’s just the only choice we have; the Lake Shore Limited route stops in 27 different locations, including a detour from New York to Boston to Albany to Erie, PA to South Bend, IN to Chicago. And it only runs three days a week. All else equal, including travel to-and-from an airport or train station, it makes more sense to fly.

To be fully complete: it’s twice as fast to drive from New York to Chicago, and using a gasoline engine, costs about the same (~$80 in fuel) as taking the train or flying. People make this choice all the time. This choice fosters competition, a Smithian favorite and supposed favorite of the laissez-faire antiplanners among us.

But rail, and especially high-speed rail, is at its most potent when we’re discussing regional travel, say along the Northeast Corridor, across Texas, or between New York and Chicago.

Let’s say instead, all else equal that the United States invested in high-speed rail—true, prioritized rail—between its port cities. Speeds on non-rival high speed lines across the world reach up to 200 mph, or just under 4 hours as the crow flies from New York to Chicago. As this blog has discussed before, and as many other smart planners/observers have reiterated, there’s a Federalism problem, a localism problem, a funding/project selection problem, a land use problem, and a problem of accurately assessing what’s possible with enough effort.

It’s a wicked trick to expect your rival to disprove a negative. We can’t say high-speed rail is obsolete, because we don’t have any high-speed rail to compare.

2. Building Highway Capacity Solves a Recursive Problem

The only problem building more highway capacity solves, by itself, is building more highway capacity. If the goal of this “free-market” solutionist is to simply pour more asphalt for “$10 to $20 million a mile,” then by all means, let’s throw money into the pit. Without a service plan tied to meaningful goals and outcomes—without defining a problem a highway (or “freeway”; free to whom exactly?)—we’d be better off not spending $10 to $20 million a mile at all on any road construction.

In fact, we’d be much better served taking that $10 to $20 million a mile and ploughing it back into maintenance, safety and operations work. If the goal truly is frictionless, fast travel only then fewer potholes overall, not just fewer potholes distributed over more lane-miles is the true solution. I’m for that. That’s a good idea.

China’s road construction isn’t slowing down because the roads pay for themselves out of tolls. China also realizes something that American political leaders have forgotten: highways drive economic growth because, unlike Amtrak or public transit, they are used by the vast majority of people.

This statement is not supposed to be funny, but it sure is. I didn’t want to break anything down sentence by sentence, but, well, here we go.

“China’s road construction isn’t slowing down because the roads pay for themselves out of tolls.”

China’s road construction isn’t slowing down because the central government decides that it doesn’t. Sure the CCP cares somewhat about its massive debt/equity positions, but any outward data are sure to be fuzzy and the central banks can simply issue more bonds to build whatever highways the government decides. Another ring road around Beijing? Sure.

The roads don’t “pay for themselves”—someone pays for them. This much of transportation economics is true no matter the government. Drivers pay tolls and these tolls are regressive—they disproportionately increase for poorer drivers who live further away from job centers. It would be something if these drivers had another option (well, besides affordable housing closer to jobs), like a train or bus system.

“China also realizes something that American political leaders have forgotten: highways drive economic growth because, unlike Amtrak or public transit, they are used by the vast majority of people.”

“China” doesn’t realize anything—Chinese political autocrats enforce top-down, central planning methods to exert control and power on provincial governments.

“Highways drive economic growth?” How does O’Toole define economic growth? He doesn’t, so I will: more new businesses, higher RGDP/capita, increased access to new opportunities, fewer public dollars spent on road projects that don’t solve problems. If I had to guess—and I do—I’d say that O’Toole means “driving faster from one suburb to another” when he says “economic growth.”

“…unlike Amtrak or public transit, they are used by the vast majority of people.”

We’ll get into this later when we talk about distorting truths with math, but this clause is missing another dependent: …who have access to it. This “vast majority of people” O’Toole is talking about is a strawman, a classical fallacy we’re taught to avoid. The number of Americans who have access to adequate public transportation for meaningful mode choice is pitiful.

In this case, I agree with O’Toole’s logic: we need to increase access to public transportation for the vast majority of people.

On a side note, even if state and local governments decide (read: stumble into and march forward with) that building new highway capacity at $10 to $20 million per mile, it’s likely that this new capacity will make traffic and congestion WORSE. This is called Braess’ Paradox, and it relies on decision theory based on information dispersion. In simpler terms, all rational actors will take a path with a perceived benefit i.e. a “faster” route with decreased travel time, independent of one another. There is no incentive to “defect” to the stable, but longer travel time. This is a good video to explain this. Maybe O’Toole has even seen it!

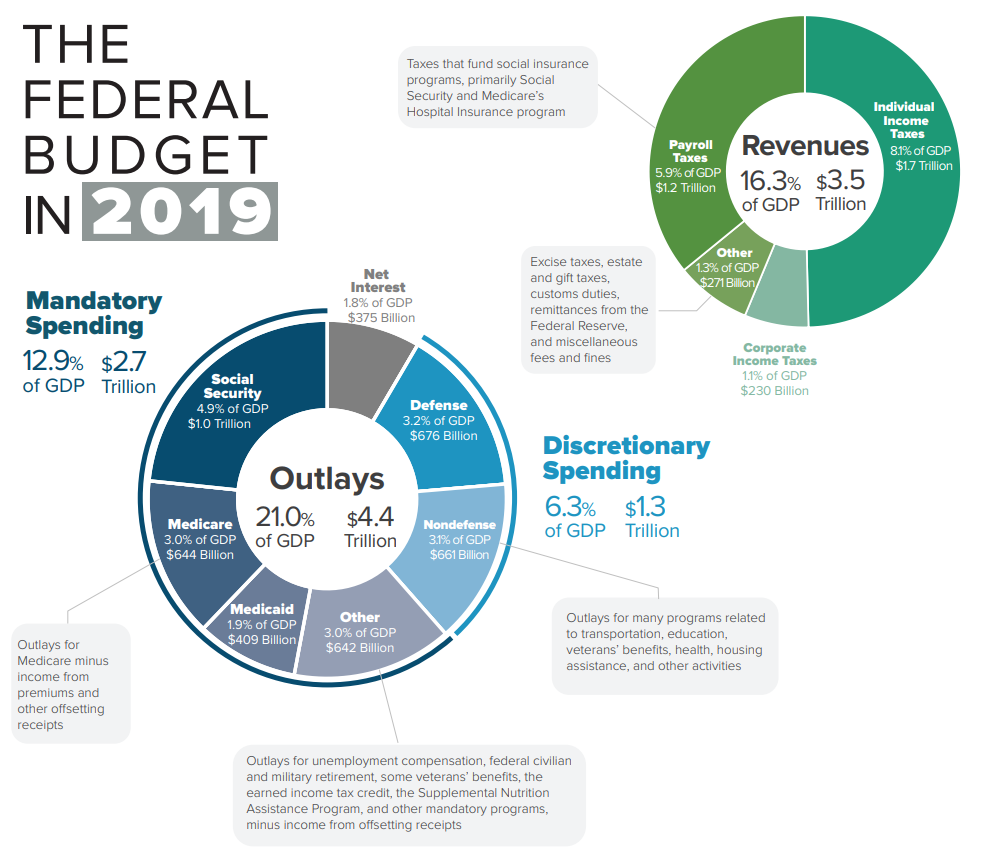

3. Public Services Cost, Not Lose, Money

There is a misrepresentation among deficit hawks and tax “reformers” that public services, like Amtrak, the Postal Service, Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, lose money; that spending tax dollars on them is akin to investing in privately-run businesses that lose money. That funding these programs that help people travel, help people communicate, help seniors live with dignity, and help people gain access to healthcare, is an affront American capitalism, or that if all of these programs were privatized, then they could be more beneficial to those who need, want, or like them.

Conspicuously, of the discretionary spending, which is spending by Congressional Act rather than by fiat, we don’t say that we lose nearly $700 billion on defense spending. It’s a cost of living in the United States, ostensibly, that we pay more than the next ten countries combined in national defense spending, none of which, it should be noted, is mandatory. The United States hasn’t even declared war since World War II, instead skirting the formal process for a more discretionary one, where Congress has “agreed to resolutions authorizing the use of military force.”1 So why do we treat military, discretionary spending differently than those programs we must fund?

O’Toole brings this misanthropic attitude toward high-speed rail, too, when referring to President Obama’s optimistic rail plans:

Without ever asking how much this would cost, Congress gave Obama $10.1 billion, which (after adding $1.4 billion of other funds) Obama passed on to the states. Except in California, no one expected that these funds would produce 150-mile-per-hour bullet trains, but they were supposed to increase frequencies and speeds in ten different corridors.

He uses the word “cost,” but he really means “waste.” He continues:

We now know, based on California’s experience, that constructing true high-speed rail in all of Obama’s 8,600 route miles would have cost well over $1 trillion. Unlike the 48,000-mile Interstate Highway System, which cost about half a trillion in today’s dollars but was paid for entirely out of highway user fees, none of the cost of building high-speed rail lines would ever be covered by rail fares. In fact, fares won’t even cover operating costs on most if not all proposed routes.

I won’t even argue with O’Toole here: he’s right about the confusing failures of American high-speed rail. We have spent billions on very little to show for it, and it makes it that much harder for rail advocates to ask for more money for another “go.” The pivot away from “bad government failure” to “failure of technology,” however, hugged in big dollars, is where this argument loses muster.

“Unlike the 48,000-mile Interstate Highway System, which cost about half a trillion in today’s dollars but was paid for entirely out of highway user fees, none of the cost of building high-speed rail lines would ever be covered by rail fares.”

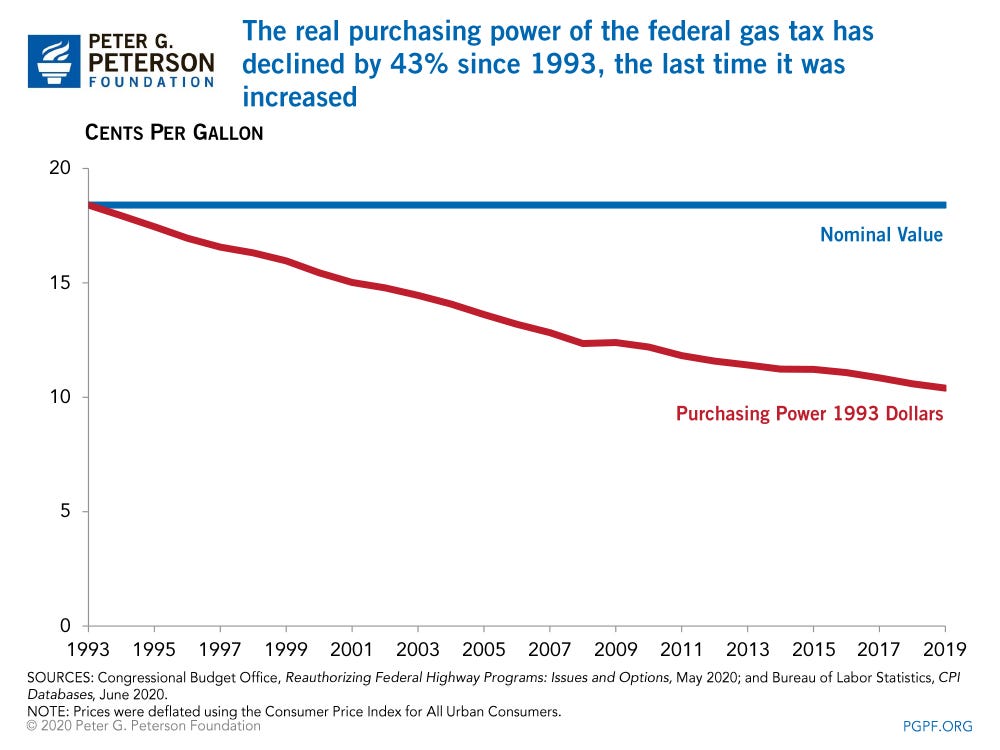

This is a strange way to shout out the Highway Trust Fund, which is, in fact, “maintained” with a gasoline tax, so sure, it’s a user fee, paid for by drivers who fill gas-guzzling cars. And in fact each year we don’t raise the Federal gas tax, the Trust Fund’s purchasing power decreases. Also, and not for nothing, all government spending is financed with taxes; the ones that we’ll use to build high-speed rail will simply come from a different bucket.

See this chart, which I’ve included in previous posts, for posterity. What is this saying? That the 18.4¢/gallon tax, which has remained static since 1993, purchases about 10¢/gallon worth of roads as of 2019; it’s less now.

This is clearly unsustainable, and to be fair, O’Toole understands this. When referring to Secretary Buttigeg’s plans for future transportation funding: “He [Buttigeg] actually suggested one such mechanism during his presidential campaign: mileage-based user fees.” Progressive transportation advocates and Pigouvian tax mavens can agree that this method is more sustainable than a gas tax, now that there’s a huge push to electrify our fleet, now that there’s more remote work than ever, and soon, when the push for public transit and high-speed rail becomes a reality.

4. We Are Floating in Success

O’Toole’s intro paragraph likens high-speed rail, which, for what it’s worth, requires precision engineering and mastery of politics, to the rotary phone. To O’Toole, a successful future is one where every spare dollar we have must be invested in lane-miles of highway or in as many airports and airplanes we can muster. He spends the remainder of this essay citing examples of speed, cost, environmental, and China, which is fine except none of his examples demonstrate why this future is preferable to any other future.

It is imperative that when we’re talking about future scenarios for growth and capacity, especially in the build environment, that we talk about how we measure success.

Speed/Cost

For example, if, like O’Toole says, we’re throwing money into a pit by investing in rail—that $11.5 billion is too much to spend on high-speed rail planning and engineering because it’s “too expensive” or that we can build roads much cheaper—then we have to talk about the benefits of this investment. If we talk about how fast air travel is, we must also talk about the benefits of saving time in terms of alternative choices—that it’s potentially more convenient (and faster, door-to-door, including travel to and from the airport, security, and enplaning/deplaning) to take a train from Portland to Seattle, or from DC to Richmond.

Aside from speed, what makes high-speed rail obsolete is its high cost. Unlike airlines, which don’t require much infrastructure other than landing fields, high-speed trains require huge amounts of infrastructure that must be built and maintained to extremely precise standards. That’s why airfares averaged just 14 cents per passenger-mile in 2019, whereas fares on Amtrak’s high-speed Acela averaged more than 90 cents per passenger-mile.

“Aside from speed, what makes high-speed rail obsolete is its high cost.”

I think we need to have a talk, first, about what “obsolete” means, let alone basic sentence construction. Just because something is expensive doesn’t make it obsolete.

“Unlike airlines, which don’t require much infrastructure other than landing fields, high-speed trains require huge amounts of infrastructure that must be built and maintained to extremely precise standards.”

Ah, yes, the very random, infrastructure-light aviation industry, just the administration of which costs at least $17 billion annually, according to the FAA. I’m glad we don’t need air traffic control to maintain a safe airspace—unlike the precise standards in railroading.

“That’s why airfares averaged just 14 cents per passenger-mile in 2019, whereas fares on Amtrak’s high-speed Acela averaged more than 90 cents per passenger-mile.”

I truly am baffled by this sentence for a few reasons:

The first set of statistics cited—the passenger revenue per revenue-mile from the Bureau of Transportation Statistics2—puts intercity rail/Amtrak at 42¢/mile versus domestic air travel at…14¢/mile.

I’ve searched through the second primary source document—Amtrak’s monthly performance report (from 2017?)3, and even if I could figure out where he’s getting 90¢/mile for Acela, I think he’s talking about revenues, which, again, is 5 times more than domestic air travel, per passenger revenue-mile.

On top of which, even in the pandemic year the cost-recovery ratio—how much revenues cover operating expenses before subsidy was 89%! We can expect this number to re-approach the 95% it was at in 2017 when travel opens up again more broadly post pandemic.

I want to point out one thing, when we talk about Amtrak’s Net Loss—and it’s almost always a loss because Amtrak’s long-distance routes cost money to provide access—the biggest indicator for Amtrak’s health is the whopping $530 million depreciation write down. This indicates, to me, that we need more investment, to eventually take offline infrastructure that’s dragging Amtrak’s books, some of which Justin Fox pointed out in his opinion piece for Bloomberg (written before the pandemic). This includes Gateway, at a nominal cost of > $11 billion.

I see: a successful high-speed rail program would earn more revenue per passenger-mile than alternatives and would be able to become a viable alternative to other modes, like air and car travel.

Environment

Rail advocates want to ignore the dollar costs and instead argue that we should have high-speed trains because they are climate friendly. But building high-speed rail releases thousands of tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere for every mile. Even if operating the trains produced fewer emissions than planes, and there’ no guarantee that it would, it would take decades to save enough to make up for the construction cost—and the rail lines must be effectively rebuilt, releasing more carbon dioxide, every 20 to 30 years.

Oh, boy. Here we go.

“Rail advocates want to ignore the dollar costs and instead argue that we should have high-speed trains because they are climate friendly.”

No serious rail advocate ignores dollar costs and no serious rail advocate argues that we should run trains solely because they are climate friendly, but they are. I’ll leave this chart here, from the EPA, which outlines operating emissions.

To have the marginal effect on atmospheric climate that O’Toole claims, we’d have to be currently building so much rail that all other new construction would be…obsolete. Want to know how I know this? The above graph measures the share of each mode’s operating contribution to atmospheric emissions. The raw numbers are measured in teragrams, just one of which equals over 1 million US tons.

“But building high-speed rail releases thousands of tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere for every mile.”

This is a red herring, like building aircraft and new automobiles—electric, autonomous, or not—don’t also release these gases? This is an example of how, if we don’t define success, any true statement seems noteworthy.

“Even if operating the trains produced fewer emissions than planes, and there’s no guarantee that it would, it would take decades to save enough to make up for the construction cost—and the rail lines must be effectively rebuilt, releasing more carbon dioxide, every 20 to 30 years.”

I like the idea that if we do decide to build thousands of miles of true high-speed rail, that O’Toole would be into funding operations, safety, and maintenance over the lifetime of the rail lines. We agree on that at least.

I see: a successful high-speed rail program would take advantage of rail’s lower emissions profile, hopefully as we fully electrify a new fleet, and attract more people to choose rail over air travel or car trips.

China

We have to stop comparing US operations to Chinese operations. Almost everything about how we build infrastructure in the US is different to that in China, from authority, to funding streams, to what constitutes success.

China’s road construction isn’t slowing down because the roads pay for themselves out of tolls. China also realizes something that American political leaders have forgotten: highways drive economic growth because, unlike Amtrak or public transit, they are used by the vast majority of people.

It’s telling that O’Toole cites how much in debt China’s rail is, but doesn’t mention how expensive it is to build ever-expanding ring roads, just around Beijing, not to mention highways across its whole landscape.

“China also realizes something that American political leaders have forgotten: highways drive economic growth because, unlike Amtrak or public transit, they are used by the vast majority of people.”

“China” doesn’t realize anything. American political leaders haven’t forgotten. There’s billions and billions of dollars worth of outstanding highway expansions on FHWA’s major projects list, and probably billions more hidden away across each state’s STIP.

Also, and again, not for nothing, highways don’t drive economic growth. At their most useful, access to highways increase access to opportunity, whether to a new job or living situation, which in turn might help drive RGDP, if someone who wasn’t working now can. However: what about the cost of owning and operating a car? It’s not free, and it can’t necessarily be so easily sliced into on-demand chunks.

The last clause is a trick of transit and rail detractors, which I’ll cover more below. The main takeaway here is that Chinese cities boast some of the most extensive transit systems in the world, and even if Chinese rail construction is mired in debt, that it’s too expensive to build, somehow China has superconnected its cities with obsolete high-speed rail, providing a trip from Beijing to Shanghai that takes just over 4 hours, which is what a similar trip from New York to Chicago could take.

I see: we should look to China for guidance on how to vision for a future. It may not be the future we can get or even one we want, devoid of serious, complementary land use planning, but at least we can point to a potential future and declare what would be successful.

5. Weapons of Math Confusion

There are a lot of “data” in O’Toole’s article; rather there are a lot of numbers interspersed within each paragraph, almost none of which prove any point. Antiplanners and noted “free market” enthusiasts will point at big numbers and scream “Waste!” when the government, which has the organizational ability (whether it uses its ability effectively is another story, and the point of this blog) to direct such large dollar sums for public benefit. This is the point of government; the opposite—the “sunset of government planning”—is the point of the misuse of data. Starve the beast, repeat that investing in public planning is a moral hazard ad infinitum, and push for privatization. It’s the bad-faith conservative playbook.

Onto some examples.

We’ve talked about the revenue per passenger mile confusion; we’ve talked about the $10.1 billion “Congress gave Obama.” I’d like to dig into the $10.1 billion appropriation, and cover the idea that Amtrak and public transit aren’t “used by the vast majority of people.”

O’Toole says, citing himself:

Now, more than ten years later, what has happened with those projects? One corridor saw frequencies increase by two trains a day. That corridor and two others saw speeds increase by an average of 2 miles per hour. Three other corridors actually saw speeds decline by an average of 1 mile per hour. Four corridors saw no changes at all. The one corridor that saw both frequencies and speeds increase also saw ridership decline by 12 percent. Effectively, the $11.5 billion was all wasted.

Again, I’d like to call attention to the narrow parameters by which O’Toole has chosen to measure this success or failure, without diving into the complexities of building high-speed rail, comparable to building other surface transportation projects, like his beloved highways, and especially comparable to building nothing at all. Which it turns out, the United States and its states does not have a tremendous amount of experience in doing; at least not before 2008, the first round of high-speed funding for many grant recipients.

A 2016 Congressional Research Services (CSR) report, written by David Randall Peterman, outlines challenges faced by US rail authorities in building effective high-speed rail projects. He asks:

Why Are the Major HSIPR4 Projects Taking So Long to Complete?

This is a question lots of transportation scholars, government reporters, and both progressive and conservative commentators have been asking for years now. Peterman continues by answering this question in the form of challenges, and it illuminates a lot.

The Challenge of Sudden Large but Temporary Grant Funding

The Challenge of Continuity amid Political Change

The Challenge of Providing Large and Stable Amounts of Funding

The Challenge of Funding a Small Number of Costly Regional Projects

I’m amazed we even have the semblance of a HSIPR program in the United States given the erratic support for it. But the money appropriated and ultimately obligated in ARRA is a blueprint—albeit an expensive one—and I’m hoping any future efforts take a serious look at these lessons learned, and others, and see the initial $10.1 billion as a cheap price to pay for the mobility and economic advantage true high-speed rail network would bring.

So, to reframe O’Toole’s point: I’d agree that if high-speed rail’s only parameters for success were speed increase and time saved, then the program is a failure. I’d even agree that by any standard this $10.1+ billion spent looks like a waste and a total loss, and because of this, conservative commentator Wendell Cox writes: “The federal government should not provide funding or loan financing to new highspeed rail projects.” But I worry that this commentary becomes the standard, when in the grand scheme of GDP, $10 or even $100 billion pales in comparison to the amount we spend on our crumbling roads each year that costs Americans over $150 billion per year in lost wages and other capturable waste.

It’s time we get high-speed rail right, not at any cost, but at the right cost, and it’s time for us to not get scared by the billions it will cost, not lose, to do so. No one benefits from scaremongering big numbers.

Second, and much more quickly, the mythical claim that “the vast majority of Americans” don’t use public transit or rail. If we look at mode share—the amount of the commuting pie taken by each mode of transportation nationally—the numbers do, in fact support this claim. But it’s a sneaky bad faith argument and it requires a denominator that counts Americans that don’t even have equitable access to these modes in lots of parts of the country.

The solution to this math problem—how to count Americans—is to ask the right questions and to not get bogged down in bad-faith populism. Lots of Americans don’t take buses, or trains, or bike or walk, because it doesn’t exist for them to do so, or it’s totally unreliable or unsafe to count as anything more than an emergency option. So either we have to increase the numerator to include Americans who would if they could take an alternative form of transportation to single-occupancy vehicles, which would make O’Toole’s math less incorrect, or we break this argument up into regions, and remove commuters who live in transit-starved (federally sanctioned) communities.

We have to do better at selling these points. It’s very hard. But we have to.

6. How and Why We Say Things Matters, A Lot

Lastly, and briefly, we’ll quickly look at how O’Toole uses adversarial language in such a way to paint government spending as at best amoral, and at worst, immoral, and by proxy paint those who believe so, the same (bold mine).

…all technologies that were once revolutionary but are functionally obsolete today…

…California ended up spending $100 million a mile building its abortive high-speed rail line…

…constructing true high-speed rail in all of Obama’s 8,600 route miles would have cost well over $1 trillion…

…[e]ffectively, the $11.5 billion was all wasted…

…[t]he last thing we need is more deficit spending building obsolete infrastructure that few people will ever use…

I understand the function of an opinion and how to sell an idea. I appreciate a well-crafted argument, especially if I disagree with it, but I do not appreciate being treated as a rube, hoping I’d then read into weak argument with an negative anchor in place.

Don’t do this. This is the weakest of my arguments, and I don’t expect this section to turn folks against this article like the other sections. I just hope that when, in the future, when we’re talking about high-speed rail, there’s a better counterargument than this, the single dumbest piece I’ve ever read.

https://www.senate.gov/about/powers-procedures/declarations-of-war.htm

https://www.bts.gov/content/average-passenger-revenue-passenger-mile

https://www.amtrak.com/content/dam/projects/dotcom/english/public/documents/corporate/monthlyperformancereports/2017/Amtrak-Monthly-Performance-Report-September-2017-Preliminary-Unaudited.pdf

High-Speed Intercity Passenger Rail