Alexander Esposito On The Past, Present, and Future of Transportation

Circuit's co-founder and chief good ideas officer dishes on how his company's service isn't out to get buses and the future of whatever the hell microtransit is.

Okay, imagine Uber, but without the baggage, hubris, and warmth.1 That’s how I’d describe Circuit, a point-to-point private rideshare service slowly making its way to your city. At least that’s how its co-founder and CEO, Alexander Esposito thinks about the future of the company he’s helped grow since 2011. Deliberate, complementary, on-demand, electric, warm, transportation. He sees Circuit as part of a larger solution to the problem: how do I get from here to there?

Our roads are so much more than car movers. Our streets are more than the sum of their rights-of-way. Alex and I spoke a few months ago about how Circuit’s working toward de-manifesting and imaginatively thinking up a new destiny for a car-optional future. Our interview is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

My name is Alex Esposito and I co-founded Circuit with my business partner, James Mirras.

Circuit is an on-demand electric shuttle service that focuses on short trips. We work closely with cities, transit agencies, and developers to build on-demand shuttle solutions, 100% electric, and help with local transport, whether that's first/last mile connections, parking issues, connecting people so they're riding together, and reducing single-occupancy vehicles on the road. So there's a variety of use cases, but the common theme is on-demand, electric, shared and intentionally focused on short trips.

Can you give a sense of the longest trip you would run?

That'll vary a little bit by market, but there's this interesting tipping point—point-six miles—which is where people feel that it's too far to walk, but not necessarily far enough to drive and so that's the shorter end of what we do. Our average trip is about 1-1.2 miles, and our longest trip would probably be in the four-mile range. But we're typically looking at downtown areas or helping to alleviate transit deserts by providing first/last mile connections to existing transit hubs.

Point-six miles is a little over a 10-minute walk at a normal walking gait, which is a barrier to taking transit, in a lot of ways—access to it. People are willing to walk about 10 minutes, or half a mile to their closest transit stop before they start to consider other options, like taking an expensive taxi or on-demand rideshare, which can be single- or multiple-occupancy, and then up to four miles, you're saying, which is, again, a little over an hour walk that no one would necessarily take.

How fast are your typical shuttles?

So we have a mixed fleet of vehicles, and our app will assign the right type of electric vehicle for the right type of use case. A little more than half of our fleet are neighborhood electric vehicles.

Those are the ones that have the speed limit limitations, and they go about 25 or 30 miles an hour and are restricted to roads with speed limits of 35 miles per hour or less. So we'll typically deploy those in more downtown settings. They're easy to hop in and out of. Occasionally we'll have these add-on services that might go a bit further in and out of downtowns. That's when we would use an EV transit van. In some cases, we will also use sedans, and that's normally a result of either speed limits and/or weather, but about 60% of the fleet are these neighborhood electric vehicles.

What problem did you identify with your business partner originally that gave you the idea to start Circuit?

It's an interesting origin story because we didn't just jump right into this. My co-founder and I went to high school together. James was working in finance and I was working in consulting in New York.

We grew up out on eastern Long Island. We were locals in an area that got completely overrun by tourists and visitors in the summer, and there was a big issue with beach parking. The initial model and the business used to be called “The Free Ride,” and the idea was: if we can get people to park in town where there's a big empty parking lot, then we can provide a free shuttle service using electric cars to the beach, to alleviate some of the parking issues at the beaches.

There was also an issue with emissions and idle vehicles…and not a great way to start a beach day. Fortunately, we were able to operate the service in a seasonal environment and funded the entire service using advertising dollars.

We realized that there were a lot of cities that had parking issues, and we also had a lot of people who were using the service to get to the train station and bus stops. And so I realized, “Wait, there's this whole first/last mile problem that's out there too.”

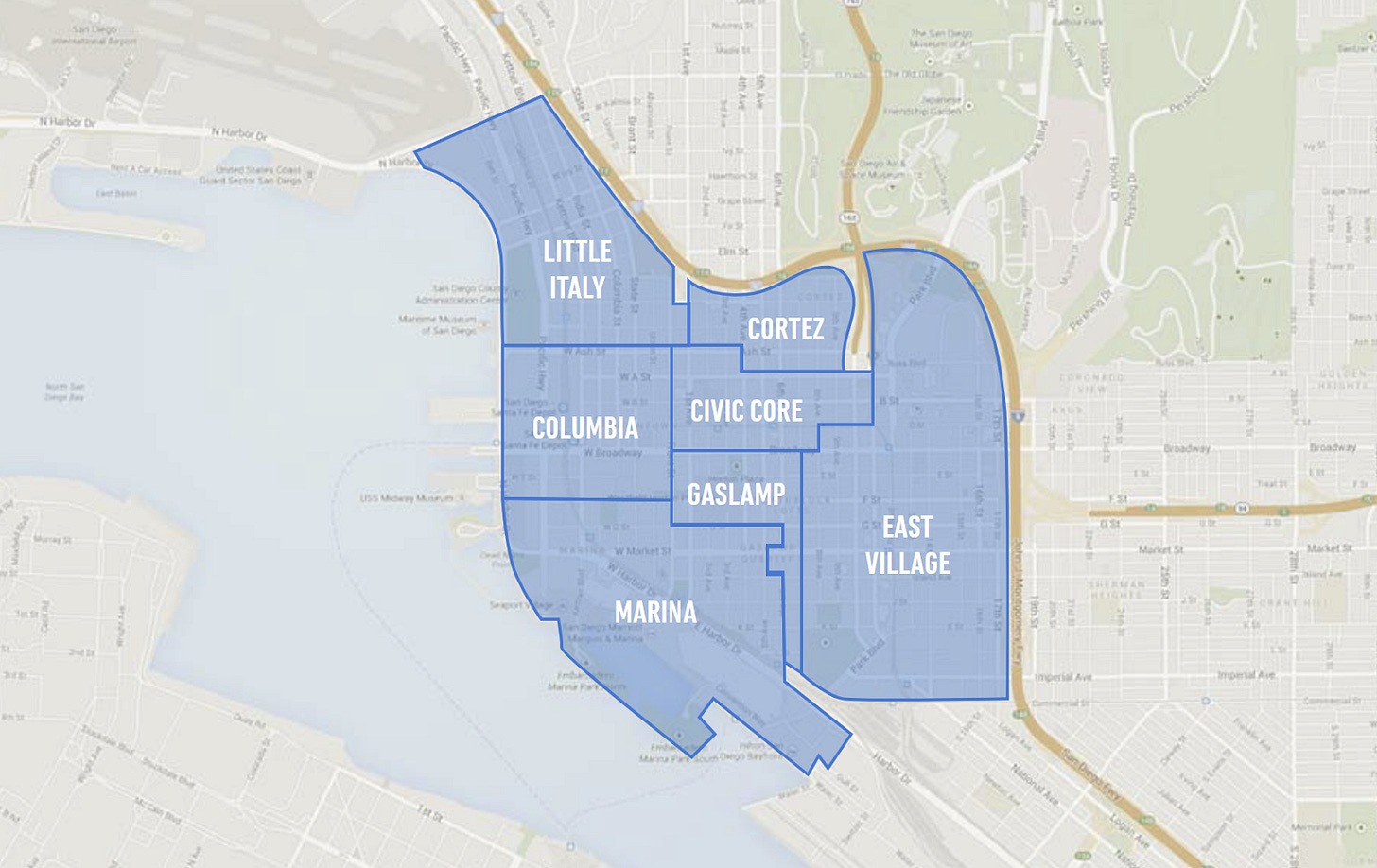

From there, we started to shift focus and started working closely with cities, San Diego was one of our initial champion cities, where we built an on-demand downtown circulator system that helped with the demand for parking and helped with transit connections. We realized that this was a lot more than just a beach shuttle, there are a lot of these short trips in cities, and they create a lot of problems for a number of different reasons.

How did you identify San Diego as your next market or the market you wanted to go into after you identified eastern Long Island?

There was an opportunity. We had an advertising partner that we were working with that was looking at San Diego for Comic Con. So we started looking at our service as event-driven. We got to talking to the Downtown Partnership in San Diego, and they explained that the city was having these big parking issues and transit connection issues.

A lot of people commute to San Diego from North County and come downtown. You can take this beautiful train ride right down along the coast, but when you get into downtown—the train’s on the westernmost part of downtown, so it's not as centrally located, and a lot of the parking also wasn't centrally located. They were looking at doing a downtown circulator shuttle, and they had worked with a few consultants to see what that might look like.

The shape of the downtown in San Diego is very amoeba-like, and it wasn't really set up well for a fixed route, where you have obvious north, south, east, and west, and so it was going to be a very clunky route, with a lot of stops, and there were a lot of questions around environmental impact, will people use this at the time?

The rideshare companies were starting to come onto the scene, and people had shifted behavior towards on-demand, so we got to talking with them and said, “We have this great solution that works as a beach shuttle, but we think it works in this urban setting.”

And the analogy was really: In a downtown area, why have three caterpillars, if you can have 15 ants? We can make them so that they're confined to the downtown area, so we're not introducing a bunch of new vehicles to the market. We can deploy them in a more granular fashion, so we don't have to run all 15 if it isn't busy (and can recharge at charge points downtown). We can stagger those shifts and line them up with vehicle charging schedules. We can pool riders, just like a bus does, by using an algorithm that'll pick people up who are heading the same way. So we're not just creating a bunch of single occupancy rides. We're encouraging a lot of shared rides.

We've been proud of some of the pooling metrics we've been able to see. It was a product of a lot of things, but we saw the report and got our heads scratching: Why are they thinking of a fixed-route bus in such a small area? This isn't a “knock” on buses—buses are great at getting people in and out of cities or from one end of the city to the other. Ultimately, buses are great when buses are full. And what we found is that in these more complicated downtown areas where you have short trips and a lot of stops, that's where you see an especially big drop off in fixed-route bus ridership. So we wanted to line this up so we're complementing the existing services, like the trains and the buses that are going in and out of the city, but providing a user-friendly and eco-friendly solution for the downtown area to encourage some of that ridership and multimodal behavior.

What year was this? Let’s orient the timeline…

It was 2016 and at the time, it was Mayor Faulconer [San Diego] who had done a “ribbon cutting.” We just had a ton of people downloading the app—the service was totally free and widely utilized at the time. Fortunately, several other cities, transit agencies, and even developers reached out saying, “We have parking issues. We have first/last mile transit connection issues; we have congestion issues.”

We realized that we were on to something bigger than the initial beach application.

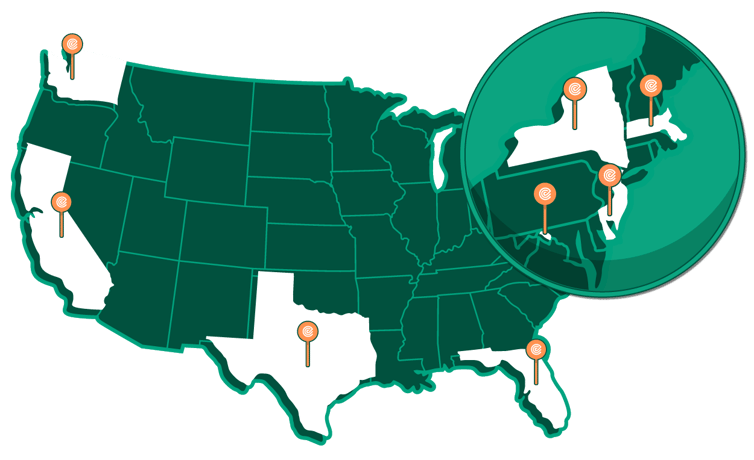

How many markets are you in today?

It's about 40 different markets. We've been focused on key regions, and what we found…is that we're not afraid of operations!

We have an employee-driver model. Our drivers are great. They're the face of the business. They really offer a level of quality control, safety, and consistency that isn't always offered by rideshare services. We also have fleets of electric vehicles, so we've been intentional about growing regionally.

The most saturated regions today are South Florida, Southern California, and the New York Metro. I'm really excited about some of the new services we've opened more recently in DC, Dallas, Boston, and Bellevue, WA.

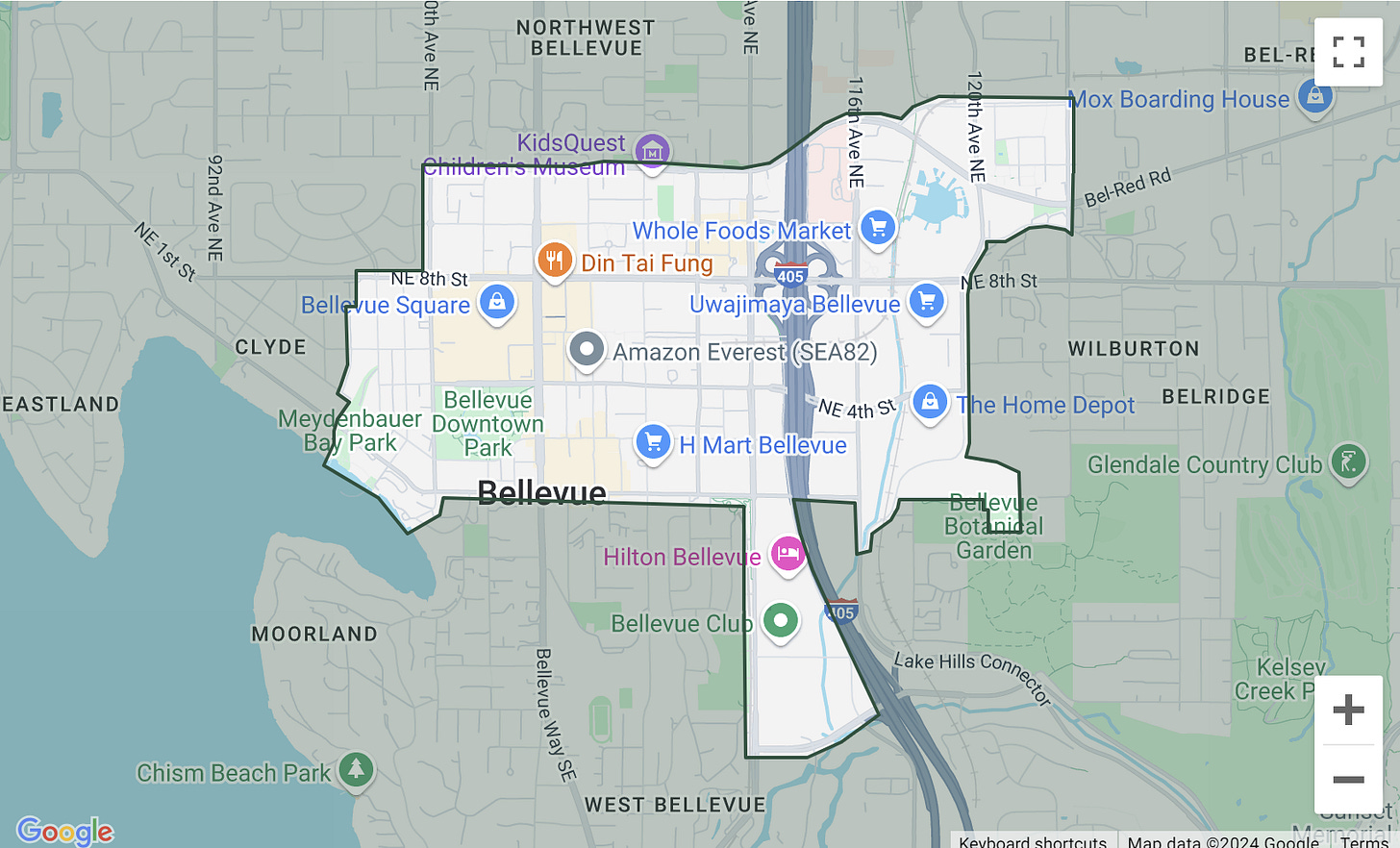

Interesting about Bellevue. It’s a size-outlier in that group. But they’re doing some really interesting things in transportation, especially, and they’re forward-thinking in terms of envisioning a future that stresses a well-connected, multimodal system. It’s cool that you're there, and that your team identified Bellevue as one of the places where Circuit could provide value.

Has your philosophy shifted at all since the beginning? What's a learning or a takeaway that's changed since you started the company?

The philosophy of the business has shifted a lot. Our mission to provide user-friendly, effective, and sustainable, short-range transportation hasn't shifted a ton, but we've identified some use cases that are more relevant than others. There have been a lot of tweaks to the philosophy though and a lot of head-scratchers too.

Starting with the head-scratchers, a realization I've had as I've continued to obsess more about the industry and the space is that the longer the trip, the more money the company makes.

I'm sure you've heard these facts in the past, but a third of all vehicle trips in the US are two miles or less; about 50% of all vehicle trips are three miles or less. That's a big problem because all these short trips add up. They cause a ton of congestion, pollution, and drain on economic development in our urban areas. So how do we solve for short trips? We can't apply that same logic—the longer the trip, the more money a company makes—to a setting where we're trying to solve for a lot of short trips. We've gotten intentional about what we're good at, and I think that's a lot of passengers per car per hour, and how we use pooling and routing and different vehicle types and different vehicle assignments to make sure that we're maximizing the number of passengers per car per hour.

Cost per rider is a really important metric in the transportation space. For the audience: there's not a public transit system in the US that's profitable, but it's also one of the best investments that a city can make when you compare economic activity and social returns. But the systems themselves aren't profitable [Ed. At all, not even close].

Companies agencies might look at how they can reduce costs and cost per rider. How much did this system cost to operate minus revenue from fares and ads, and then divide that difference by ridership? If we focus on the rider—the denominator in that equation—and we get more people to use the service by making it safe, dependable, and user-friendly, then we can make a real impact on cost per rider. That stood out to us more recently than initially, when we were operating as a beach shuttle.

I want to dig into the idea of profitability, which is a big challenge in our industry, and reframe the thinking a little: what does it mean to provide a profitable system? Obviously, that means your revenues exceed your costs. It’s generally understood when you run a business, whether it's a government “business” or it's a private business, that you want your revenues to exceed your costs. But from a transit perspective and from a public service perspective, that's not always—especially recently—the case. We have to rethink what profit means and who gets to share in those values.

Where do you see Circuit taking some of the pressure off these agencies to run this unprofitable service? Yeah,

There are a few different answers there, and this is something that I'm passionate about.

If we're just talking the math, there are situations that we've seen where—not a knock at buses and buses are great when they're full—but we need to look at when buses aren't full. That's where things get expensive. If you're paying a driver and paying for a really big vehicle to drive a really small number of people around, then it's going to cost you a lot on a cost-per-rider basis. We've seen some situations where we run a more cost-effective, electric service that doesn't have to deal with fuel costs, has significantly lower maintenance costs, and can deploy more dynamically

If you don't need all of the seats at the same time, you can almost “break that bus up” into other pieces and run service more efficiently. We have seen situations where we've been able to reduce costs by replacing systems, but that's not usually our intention. Instead, we’ll ask, “How do we help the denominator [Ed. aka increase ridership] for those other services?” What I mean by that is: if the cost provider on a train or a longer range bus system is really high because not enough people are using it, then can you use a first/last mile connector shuttle like Circuit to get more people to use that train and that existing infrastructure? How can we not rebuild the infrastructure or create new infrastructure, but instead: how can we make it more user-friendly for people to use existing services?

If you [a potential train or bus rider] can click a button and get dropped off at the train station, you're probably more likely to use it than if you have to try to figure out how you're going to get there or pay to get there. Agencies can start to look toward increasing fares via an increase in steady ridership.

The other question about how you measure the economic returns of transportation investment is really important and is often overlooked by the general public. What would New York be without the MTA? It’s how tourists get around and how people get to work. That's how jobs are created. There's a lot of value that transportation provides, whether it's job creation and economic activity or it's reduced traffic that leads to increased productivity.

We're expanding access, which means potentially reducing commuting costs in low-income communities. Creating access to transportation in turn creates access to more jobs. Then you can look at the environmental impacts; you can look at public health from an air quality perspective. There are so many benefits to transportation investment that it's easy for anybody to get behind them. I don't think it should be a polarizing issue.

There are all these hidden costs—these opportunity costs that are not necessarily expressed in how someone might behave. What they see is: fares are going up and service shrinks. “What value am I, a taxpayer (and let’s call it investor in the system), getting in return for my investment? Why should I invest my hard-earned money in transportation?”

It's a question that we have to reckon with as professionals because there's a limited pool of resources and people's attention and dollars and time to go around. So I guess my question is why couldn't transit agencies do what Circuit is doing? “Why shouldn't they” is an even better question?

First of all, we can move really quickly, and that’s difficult for large agencies or authorities. It's also more complicated than it looks at first. We have fleets of electric vehicles and those electric vehicles have charging schedules. We have teams of W2 drivers [Ed. Employees, not contractors], and not all of our drivers show up at the same time in the morning and leave at the same time in the evening. We stagger all of those shifts; some will be full-time, and some will be part-time.

Rider demand isn't constant throughout the day. There are peaks and valleys. Our operations side has done a really good job and built some great technologies to play that game of Tetris on the back end. How many vehicles? When should the drivers be staffed? When should these vehicles be charged? How do we line all of that up with the rider demand schedules and patterns so that we can run an optimal service and continue to improve, tweak, and refine that service over time using data that the services are collecting?

And then we're constantly developing and building new features and enhancing the features that we have, improving the routing and zones, and so…it's a living project.

The other part of that question is do they [the transit agencies] want to do this? One of the things that I've experienced when working with planners is it's a big project on the city side, the market is fragmented, and if a city were to do something like this, they'd have to run a procurement process to better understand: what type of vehicles should we get? Let's test these. Has anybody else used these? How do we insure these? How do we charge these and maintain them? And then: who's going to run this program? How do we figure out what the geofence coverage area should look like? How do we know what the hours of operation should look like? And then, if they want to get fancy, maybe they work with a transit tech company that tells people where the shuttles are going or where the bus is going. Is there a white-labeled app?

Let's make it easy for the customers. We have a lot of experience doing this. We have a lot of data. We can compare markets to other similar markets where we've been successful. We've also learned a lot of things the hard way over the years, and so our ability to provide that turnkey solution has been really embraced by our customers because we work closely with them.

At the end of the day, we can come to what we think is the best solution, and then they can lean on us and trust that will get the job done for them.

I was hoping you were going to tap into the idea of core competencies—what a transit agency should and can do distinguishing the delivery of all these different services.

What the MTA should be doing is running fixed route short, medium, and medium-long distance service to get people throughout this absolutely massive, gigantic city [New York]. Transit agencies do some on-demand services, but increasingly, cities and regions are contracting out a lot of their on-demand paratransit services for people who have mobility challenges. These customers can't necessarily interact with our fixed systems in the way they would like, but these customers still deserve dignity and access to mass transit.

We're seeing that growing trend of matching the demand with the supply. The fact that there are more and more companies like Circuit and others willing to provide these services—not only seeking profit but also trying to push a mobility mission. It’s a great use case and a great sales case for why products and services like yours continue to exist.

It is a really fine line because I do think that there are other companies that have attempted to be the silver bullet in transportation, and we've been fortunate to not be naive and to be really intentional about trying to complement and not compete with certain service, because there are areas where fixed-route makes a lot of sense,

The word “microtransit” might need a firm definition, because I've seen some situations where we're talking about 50 square-mile coverage areas, and there's not too much “micro” about that. And when you start to put a service like that in place on a really big area that might be better handled by fixed route, then you're going to see these astronomical cost-per-rider numbers—you're basically subsidizing taxi rides. We've tried to stay really focused not on, “How do we replace a bus in this 50 square mile area, but how do we create these pockets where we can get people to the bus so they actually use it.”

Communicating this idea to a public that just wants to get to work, school, doctor, or airport—they don't often care about all these different ideas. Bridging that communications gap from the Federal government (where money comes from, most of the time) down to the individual citizen (who pays for and uses many different transportation options) about what it is that the system is supposed to be doing for them is a big, big challenge. We’ve got all these different ancillary well-meaning actors, like private industry, nonprofits, and advocates that are trying to interpret and reinterpret and make some space for themselves to be the authority on what different laws and mandates mean.

How does Circuit stand out?

What's interesting is how valuable the employee-driver model is in our business. Drivers really start to become “ambassadors” for a reason and we always try to hire locally, because there's so much customer service and marketing value there that is often overlooked when you're staring at a spreadsheet. Drivers are talking to riders every day and are to develop this community feel in our markets, which adds an extra benefit for repeat riders.

I was down in Florida in one of our markets, and in the car, we picked up a senior who was going to the grocery store—she goes to the grocery store every Wednesday—and oftentimes it's one of the same drivers that's picking her up every Wednesday because they work every Wednesday afternoon. It really aids in the education and marketing aspects of Circuit’s services. It’s often overlooked: we’re not just moving the vehicle around. There's a lot of value there that the drivers unlock.

There's an opportunity if you create a positive customer experience at any interaction, maybe with a station agent or with your driver, you're creating this goodwill. Each interface is a great way to—

—there's a safety and trust element there too—

—the safety and trust element for more vulnerable people, or people who want to feel a certain comfort with their transportation. People want to have pride in moving around their city, and feel that level of independence, and feel safe and secure. Circuit being just one part of that can be a huge boon for the future of what it is we're doing here.

Let’s move on to some current initiatives. What's a new problem you've identified, and what's the approach to solving it?

It might depend on the day, but I think one of the exciting problems that we’ve found in a number of our markets is that demand will outpace supply. That's a good problem from the planner’s perspective, in that we’re funding a service that's being highly utilized. But the flip side of that is that if you have a fixed number of vehicles and demand is outpacing the supply of vehicles, then you start to see wait times tick up.

I'm excited about some of the technical back-end improvements to our vehicle deployments. We now can send a bigger vehicle if it's a larger group, and a smaller vehicle if it's a smaller group taking a short trip. Intricacies go a long way when you run those small gains across large volumes. We've also found a lot of value in really low fares. A lot of our services are totally free and fully subsidized by our partners, but in some markets, we've implemented a $1 fare, and we've seen a pretty significant impact on efficiencies and a lot of that is driven by reduced cancellations. Once you assign a $1 value to it, somebody's less likely to cancel, or they're less likely to go for a joy ride because they want to show their friend who’s visiting the area.

We've also been able to, in working with some of our other partners, deploy those fares more dynamically. So let's keep it free downtown. It's good for employees who work in the downtown area. It's obviously good for getting customers to the downtown area. But if you're outside of downtown and you're at your house, and you're going to your friend's house, then maybe we should put a small $2 fare on that. We work out a revenue share program with the partners, and some of that money goes back into the system so that we can either expand the size of the fleet or adjust the operating hours, etc.

This is one of those good problems, and I've been excited to see how small adjustments can really go a long way when you run those across the volume of riders that we see.

What can transit agencies learn from how you're operating as a low-fare or fare-free model?

There's one other component to the revenue. The bulk of our revenues do come from our transportation partners, sometimes a transit agency or sometimes a program with a state agency like NYSERDA [New York State Research and Development Authority] in the Rockaways, or directly with San Diego, West Palm Beach, Fort Lauderdale, and several others.

And so our ad sales team, led by Alyson Brown, works with both local and national brands on innovative, localized marketing efforts, whether that's a mix of wrapping the vehicles or some cool stuff in the app. Fares are probably the last and smallest revenue stream, and we share parts of both the ad and fare revenue with the partner, through a revenue share program, to reduce its costs.

Again, there's no silver bullet in transportation. Some services are great at paratransit, great fixed route operators, and then there are companies like Circuit that are good at this first/last mile, high frequency, lots-of-passengers-per-car-per-hour services. Trying not to come up with a catch-all solution ultimately leads to more successful systems.

Would you say that your greatest competition is human-powered movement—walking?

No, I wouldn't. It depends on how we define competition, right? Riders have other choices to get around, and if people can walk, then they should, or if they can take a bike and the weather permits, then that's great, too. But there are a lot of people who can't do either or don’t want to.

We've actually asked a lot of our riders through surveys, “Do you ever use Circuit to go one way?” And it's been really interesting to see that the service has actually helped with walkability in a lot of cases. We’ll get answers like: “Maybe I want to walk there, but I don't want to get stranded there, because I think it's going to rain later, and at least I know Circuit is available on the way back…” or, “I have a meeting, and I don't want to be sweaty when I get there, so I'll take Circuit, and I'll walk on the way home.” All of these inputs really work together in that way so I don't think walking is a competition.

There are a lot of different private shuttle operators out there. There are different transit tech companies out there, but I don't know that there are any companies that are good at that turnkey solution that's specifically designed for a short-range environment. And I think that's where we've carved out our niche.

Can you identify what a successful future looks like for the industry, Circuit, and you personally?

One of the biggest problems that we're facing…. there are just too many cars on the road. And that's not news to anybody, so I envision a future where people don't drive around cities and single occupancy vehicles aren't used in cities. Instead, we’ll use connected, shared, electric transportation. Eventually, it might be autonomous, too, and today there's a lot of great technology available that's a huge improvement from what we're used to seeing.

In the future, you might take your car to get to a city, but once you're there, you use shared electric transportation to get around the city.

That also means packages too... Today, riders are really the focus, but if we can use those same assets at night to deliver packages, then that's making better use of existing infrastructure and existing assets to reduce the number of vehicles that are on the road. Ultimately, that's what we all need to solve for. And it's one of these really big problems, and it's complicated to solve, but it's really simple to find the heart of…it’s just vehicle miles traveled. It's a pretty simple equation: reduce those and traffic gets better. [Ed. All else equal.]

I know you're a very employee-driven company, but labor is often the biggest cost factor in service delivery. How are you envisioning the balance between labor and autonomy?

Autonomy is interesting, but it's also going through this “S”-curve, as we see in all technology development: people fall in love with the technology, not the application, and then there are a few misses, and then all of a sudden, “No, this will never work…” And then, “Wait it works well in this use case.”

For example, let’s say you and I are going to a Yankees game, and we're somewhere in Westchester, and we say,” Oh, it'd be cool to have a robot drive us there, and we're willing to pay $100 for that, then that's going to be a fun experience.” That's very different from, “How do we reduce the cost per rider in a first/last mile setting?” The industry as a whole is going to have to spend some time figuring out where these use cases make the most sense, and that's a product of the technology hurdle.

That's a product of the regulation, but there’s also a public adoption and social adoption hurdle: do people want robots running around their neighborhood? The last part is the cost part. “Oh, you don't have to pay for a driver? It's cheaper.” Well, you have to pay for a million-dollar robot and engineers to maintain that robot.

Drivers also provide a lot of value outside of just driving the vehicle. It's going to take quite a bit of time for the cost equation to make sense in the settings that we operate in. I'm not naive, but again, jobs will still be created because of the shift to autonomy—maintaining the sensors, maintaining the vehicles, and maybe those assets can eventually move more people per asset—but that doesn't mean you don't need people working. They may just be working in different areas. We're a long way from there, and it's going to be a gradual adoption.

You don't just flip a light switch and the whole world changes. It's going to happen over time. Outside of vehicle automation, we think about AI and how people need to be using these types of tools so that they can individually become more productive.

If everybody becomes more productive, that doesn't mean we need fewer people. It means we as a society can do more with less.

We should enjoy technological change. It should be an enjoyable process that we go through as we learn more about each other, as citizens of our various communities, and understand and connect on a deeper level. What it is that we're looking for from the spaces that we live in, and what future do we want to leave our children…? is a question of we're never going to agree a hundred percent, but if we can least get together and move in _a_direction.

I understand the need and the desire to want to be in the future already. We can also sit back and enjoy the ride, to use another cringe transportation metaphor. We need to sell this idea that there's a more connected future if we all have a part in it. And I'm hearing that's what that's what Circuit wants to be part of.

We'll continue to try to stay flexible so that we can change with the times. There's a lot of incremental gains to be had along the way. It won't just be a waterfall at the end.

You can learn more about Circuit (and download the App) here.

This post, like most of the posts on EXASPERATED INFRASTRUCTURES, is free to read and free to share with your networks. This blog is slower than usual and is a labor of love. I hope to be able to continue writing with your support. A paid subscription is the best way to help, but simply reposting my work for your networks is honestly just as good. I love you, dear reader. Thanks for sticking with me.

Just kidding.