Overthinking Transportation Funding Reform & Policy: Steelmanning Reauthorization II(a)

Anatomy of a Bill

In a fit of acronyms, we’re going to walk through past bills at a brisk pace. The goal of this post (and the upcoming one) is threefold:

To break down a reauthorization bill—ISTEA (1991). This bill was signed 30 years ago and the world has since materially and socially been ripped apart. What did it say and what are some lasting impacts?

(Next post) To track different issues through time: highway funding, rail funding, transit funding, and “other” programming. We’ll see that USDOT’s purview has only increased—perhaps not proportionally to the number of pages in each bill.

(Next post) To offer a plea toward caring about this at all. Why should you—staffer, advocate, citizen—care about what’s in this bill?

Let’s remind ourselves where we are in this long-ish process of exasperation:

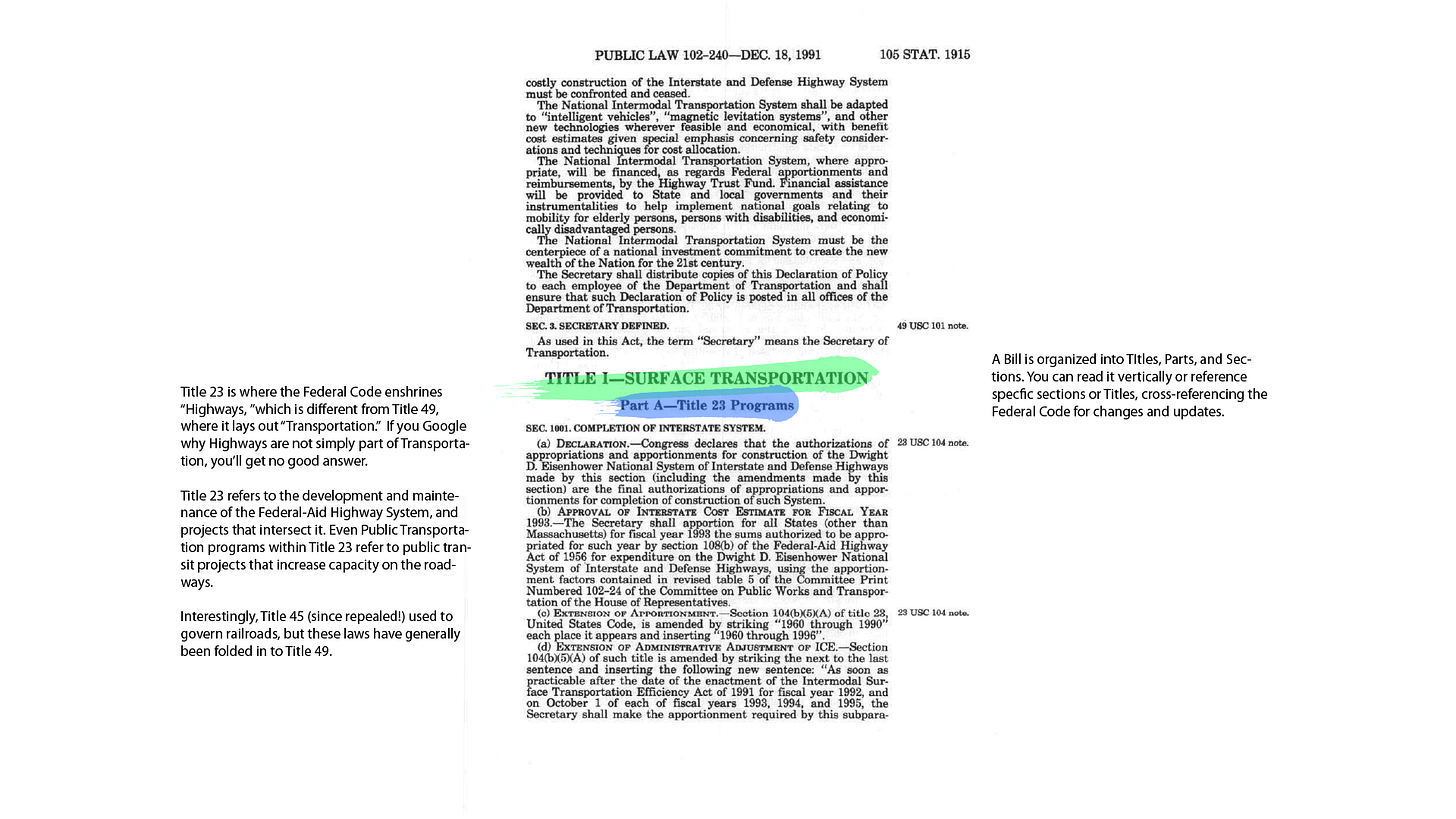

At their core, laws are statements of intent and the rules that follow. Federal law is written to amend the United States Code, which is the book of standards and regulations that guide how the Federal government operates and interacts with its citizens and other levels of government—states, cities, MPOs, counties—and other sovereign bodies. For our intents, we care about Titles 23 (Highways) and 49 (Transportation) and how Congress writes laws that change the text.

How to read a Bill (in theory).

The trick (secret) to reading law is twofold:

It’s mostly written in legal gibberish and

Ninety percent of a bill’s text is not important to read closely; nine percent is meaningful enough to have on hand as information and a final one percent is often truly groundbreaking new policy and rulemaking.

Save for committees and legal editors, very few people will actually read a bill from summary through approval. It’s often not necessary and there’s often not a whole lot in there that needs to be committed to memory. One of life’s great joys is that information is available at the notice of need—and for Federal law, there will be multiple places to access the text, and hopefully, interpretation of the text; the translation into English is key to disseminating the information to people who need it.

Transportation/legal scholars will be able to pull up the necessary information more quickly; they’ll make the connection to other strands of law/policy/norm/rule more efficiently. This skill and expertise takes time to develop and the forking of bill comprehension to contextual framework building to ease of communication about major points and how this affects an individual is a path I’m hopeful EI can help.

How to read a Bill (in practice).

I read ISTEA—the “Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act”—of 1991 and you probably should, too, if you want to take the ideas you read here seriously into practice.

The Bill is 294 pages long, but if we apply our math—265 pages are references, 26 pages are important changes/rules that might affect how you interact with the Federal apparatus and 3 are truly important and groundbreaking. The policy written into these laws fundamentally altered the rules and reorganized a dollar’s path from quite literally thin air to your streets, roads, buses, trains, etc. I pulled out 6 pages of the nearly 300 and marked them up sort of haphazardly below.

The first few pages of a bill are important to read: ISTEA’s front matter states what this bill is doing. Note there’s no Table of Contents, which is odd, but not the end of the world. The Statement of Policy hasn’t made it into many more contemporary bills—but it’d be something I’d like to see more upfront. I’d also like to see a clearer and deeper summary of changes right up front to help comprehension.

If you’re so interested the Federal Code is here.1 It’s also written in Legalese, presumably to hold it up to legal scrutiny. Reminder: this bill—and all subsequent transportation bills affect Titles 23 (Highways) and 49 (Transportation). I’m curious if we’ll see Title 23 folded into 49 in our lifetime(s).

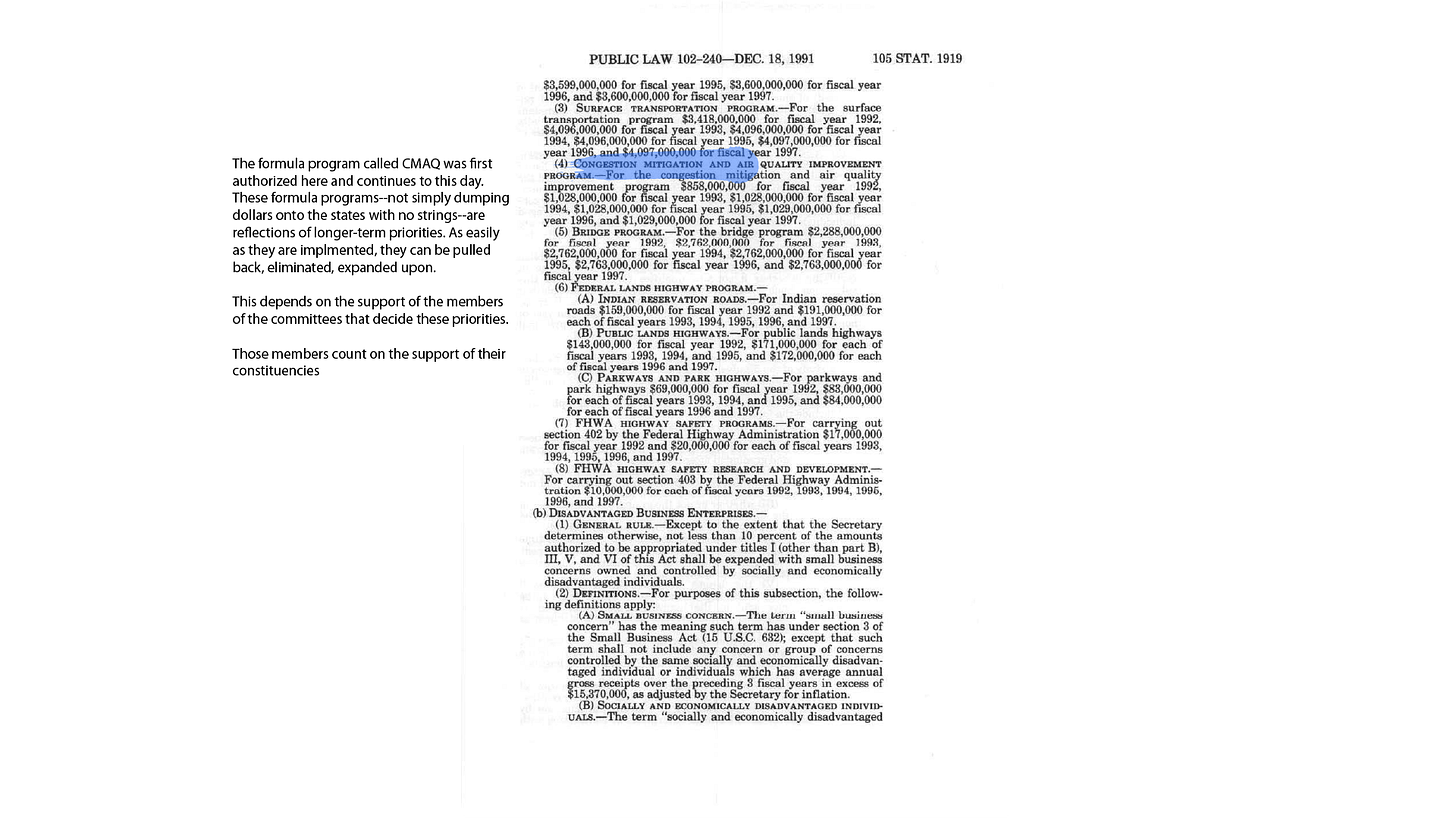

There’s nothing particularly special about the below page, except for the language about CMAQ (Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality) funds that are simply authorized and money appropriated here. CMAQ has proven to be a fundamental program in the development of multimodal projects (since it doesn’t specify the mode CMAQ funds can be used for…so transit projects count) and has been reauthorized and expanded in more recent bills, including IIJA, passed in 2021.

These earmarks2 are very weird and there’s an ongoing exchange about whether these infrastructure bills should pick project winners right up front or if they should be left to the states to pick once they know the money is allocated for projects. By tying up money de jure we leave less flexibility, should the needs or conditions change, but we do have clarity about how the spending authority would or should be used. We do require more accountability and audit to truly ensure the money goes where it should, but earmarks should make that process easier (should we choose to fund and require oversight). See: Bridge To Nowhere.3

There are dozens of pages that simply list projects, including “High Priority Corridors” below. You’ll find that (often, always) every state has at least one project and funding tied to the project as these projects and priorities are traded; that’s a recipe for corruption and very obvious misuse of power. Comment below for a deeper discussion about earmarks.

This is just a fun fact. We love facts.4

Perhaps the single most monumental change in ISTEA and its lasting legacy is the shift mandated for Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs), organizations (over 400!) that organize regional transportation planning and spending priorities to be collated with state needs.5 This monumental change was first introduced in Title III, Section 3012, and has had ripple effects that affect all transportation planning efforts across the United States.

MPOs’ original mandate from 1962 shifted to a more rigorous role after ISTEA allocated more Federal money directly to them, and required, for the first time, Transportation Improvement Programs (TIPs) and Long-Range Transportation Plans (LRTPs) in formal collaboration with State DOTs, among other activities laid out in the law.6 Organizations like the Association of Metropolitan Planning Organizations (AMPO) have much more information about the vital role MPOs play in the transportation planning process and priorities for the future of reauthorization, including an even more expanded role in planning efforts.

A Timeline of Sorts Since 1987.

It’s important to add some additional history to our discussion. When I opine about a specific bill or timeline or talk about modern transportation reauthorization, I’m generally referring to the bills since 1987—the Surface Transportation and Uniform Relocation Assistance Act (STURAA) through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) for one reason: the shift away from highways to a broader sense of surface transportation, more generally. This shift made our funding process more complex, more comprehensive, more cooperative (in theory), and more continuous (in general).7

It also gives us 37 years of history, policy, and politics to compare. We’ll have a broad base of bad and less bad to understand how we can meaningfully and, probably more importantly, actually pass a bill that moves us forward in 2026 (probably 2027).

A key component to many/much of the transportation legislation since 1987 is its insistence on responding to new information as if it doesn’t exist. We build policy like a pyramid lottery ticket; our entire Federal Code is based on a scratch-and-rewrite mentality. We do this because it’s a lot less complex than tearing the government apart every time we have a new idea. Over time we’ve slipped pretty deeply out of sync—and we can find a ton of interconnected reasons why this is the case. There’s no easy answer here. We don’t have the unique opportunity or the time to rethink transportation spending all at once, but we have an obligation to do it. Conditions have changed. Our planet depends on it; our people need it. Lives depend on it. Livelihoods rely on it. Why are we so unimaginative?

to be continued with a dive into broad strokes (mode, flexibility, complexity, and geography x relative impact) early next week (or sometime soon).8

An interesting observation from a middle-close read of the Code is that Title 45, “Railroads,” has been repealed and much of the policy and guidance has been folded into Title 49, “Transportation.” Railroads used to be _so_ important to the growth of the US that they were treated specially by the government.

Earmarks are “any congressionally directed spending, tax benefit, or tariff benefit that would benefit an entity or a specific state, locality, or congressional district,” according to House and Senate rules. This conversation is outside the scope of this piece, but earmarks are a rare topic that gets bipartisan acceptance and pushback because there’s no real right answer about whether they’re good or not. So everyone loses. One final fact to know about earmarks is, though they’re allowed, they’re capped at 1% of the appropriation amount; this is still a lot of money, but for perspective what they stand for is more important than how much they stand for.

Earmarks, however, can target interest from Congresspeople and Senators who may or may not otherwise care about transportation funding, or deprioritize it for a number of reasons. This attention is helpful in some circumstances when looking for votes or support but can be detrimental if a particular provision or project group is unpopular.

Earmarks also encourage influence trading and prerogative pawning—sometimes called logrolling—and can once again, be great for bill cohesion or literal, cartoonish corruption.

Many astute readers will be familiar with this project. It’s a literal meme.

That’s an opinion.

Sometimes MPOs will participate in or lead regional planning more holistically, but MPOs are diverse bodies and sometimes find themselves in messy arguments with local governments (when local govts are night (not) fighting amongst themselves), which always control land use and land controls. There are daily, monthly, yearly, and millennial battles among the sometimes dozen stakeholders that have specific government authority over a single site, or for our purposes, road, street, or corridor.

And how!

Well, well, well. What do you know: these are the 3Cs that MPOs are compelled to coalesce around.

There will be a matrix.

Love this series. And I’m inspired by your question of: “Why are we so unimaginative?”…Honestly, I think it’s because caring is exhausting. But it’s also what makes us human. When you mix that burnout with the feeling that the system is too broken to fix, and the temptation to give in to bandaid fixes (which are too often soaked with the infection that caused the wound in the first place)—we get stuck. Caring burns us out, but it’s also what keeps us moving forward. And that’s where the opportunity lies.

Imagination isn’t absent—it’s constrained. Unleashing it requires us to take actionable steps, however imperfect. The steps? Not sure what they are but we need to keep caring. Embedding a mindset of transformation into every policy conversation? The transpo policy landscape we navigate is sooo messy—but it’s not immune to the force of collective, intentional change. That’s the challenge and the promise: to act as if change is possible because it is. We just need to get on the same page and start singing the same tune (I’m on my soapbox). Can’t wait for part III!!!!!